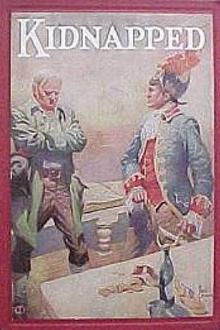

Kidnapped by Robert Louis Stevenson (e manga reader .TXT) 📕

Read free book «Kidnapped by Robert Louis Stevenson (e manga reader .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Robert Louis Stevenson

- Performer: -

Read book online «Kidnapped by Robert Louis Stevenson (e manga reader .TXT) 📕». Author - Robert Louis Stevenson

CHAPTER XXVII I COME TO MR. RANKEILLOR

he next day it was agreed that Alan should fend for himself till sunset; but as soon as it began to grow dark, he should lie in the fields by the roadside near to Newhalls, and stir for naught until he heard me whistling. At first I proposed I should give him for a signal the “Bonnie House of Airlie,” which was a favourite of mine; but he objected that as the piece was very commonly known, any ploughman might whistle it by accident; and taught me instead a little fragment of a Highland air, which has run in my head from that day to this, and will likely run in my head when I lie dying. Every time it comes to me, it takes me off to that last day of my uncertainty, with Alan sitting up in the bottom of the den, whistling and beating the measure with a finger, and the grey of the dawn coming on his face.

I was in the long street of Queensferry before the sun was up. It was a fairly built burgh, the houses of good stone, many slated; the town-hall not so fine, I thought, as that of Peebles, nor yet the street so noble; but take it altogether, it put me to shame for my foul tatters.

As the morning went on, and the fires began to be kindled, and the windows to open, and the people to appear out of the houses, my concern and despondency grew ever the blacker. I saw now that I had no grounds to stand upon; and no clear proof of my rights, nor so much as of my own identity. If it was all a bubble, I was indeed sorely cheated and left in a sore pass. Even if things were as I conceived, it would in all likelihood take time to establish my contentions; and what time had I to spare with less than three shillings in my pocket, and a condemned, hunted man upon my hands to ship out of the country? Truly, if my hope broke with me, it might come to the gallows yet for both of us. And as I continued to walk up and down, and saw people looking askance at me upon the street or out of windows, and nudging or speaking one to another with smiles, I began to take a fresh apprehension: that it might be no easy matter even to come to speech of the lawyer, far less to convince him of my story.

For the life of me I could not muster up the courage to address any of these reputable burghers; I thought shame even to speak with them in such a pickle of rags and dirt; and if I had asked for the house of such a man as Mr. Rankeillor, I suppose they would have burst out laughing in my face. So I went up and down, and through the street, and down to the harbour-side, like a dog that has lost its master, with a strange gnawing in my inwards, and every now and then a movement of despair. It grew to be high day at last, perhaps nine in the forenoon; and I was worn with these wanderings, and chanced to have stopped in front of a very good house on the landward side, a house with beautiful, clear glass windows, flowering knots upon the sills, the walls new-harled* and a chase-dog sitting yawning on the step like one that was at home. Well, I was even envying this dumb brute, when the door fell open and there issued forth a shrewd, ruddy, kindly, consequential man in a well-powdered wig and spectacles. I was in such a plight that no one set eyes on me once, but he looked at me again; and this gentleman, as it proved, was so much struck with my poor appearance that he came straight up to me and asked me what I did.

I told him I was come to the Queensferry on business, and taking heart of grace, asked him to direct me to the house of Mr. Rankeillor.

“Why,” said he, “that is his house that I have just come out of; and for a rather singular chance, I am that very man.”

“Then, sir,” said I, “I have to beg the favour of an interview.”

“I do not know your name,” said he, “nor yet your face.”

“My name is David Balfour,” said I.

“David Balfour?” he repeated, in rather a high tone, like one surprised. “And where have you come from, Mr. David Balfour?” he asked, looking me pretty drily in the face.

“I have come from a great many strange places, sir,” said I; “but I think it would be as well to tell you where and how in a more private manner.”

He seemed to muse awhile, holding his lip in his hand, and looking now at me and now upon the causeway of the street.

“Yes,” says he, “that will be the best, no doubt.” And he led me back with him into his house, cried out to some one whom I could not see that he would be engaged all morning, and brought me into a little dusty chamber full of books and documents. Here he sate down, and bade me be seated; though I thought he looked a little ruefully from his clean chair to my muddy rags. “And now,” says he, “if you have any business, pray be brief and come swiftly to the point. Nec gemino bellum Trojanum orditur ab ovo—do you understand that?” says he, with a keen look.

“I will even do as Horace says, sir,” I answered, smiling, “and carry you in medias res.” He nodded as if he was well pleased, and indeed his scrap of Latin had been set to test me. For all that, and though I was somewhat encouraged, the blood came in my face when I added: “I have reason to believe myself some rights on the estate of Shaws.”

He got a paper book out of a drawer and set it before him open. “Well?” said he.

But I had shot my bolt and sat speechless.

“Come, come, Mr. Balfour,” said he, “you must continue. Where were you born?”

“In Essendean, sir,” said I, “the year 1733, the 12th of March.”

He seemed to follow this statement in his paper book; but what that meant I knew not. “Your father and mother?” said he.

“My father was Alexander Balfour, schoolmaster of that place,” said I, “and my mother Grace Pitarrow; I think her people were from Angus.”

“Have you any papers proving your identity?” asked Mr. Rankeillor.

“No, sir,” said I, “but they are in the hands of Mr. Campbell, the minister, and could be readily produced. Mr. Campbell, too, would give me his word; and for that matter, I do not think my uncle would deny me.”

“Meaning Mr. Ebenezer Balfour?” says he.

“The same,” said I.

“Whom you have seen?” he asked.

“By whom I was received into his own house,” I answered.

“Did you ever meet a man of the name of Hoseason?” asked Mr. Rankeillor.

“I did so, sir, for my sins,” said I; “for it was by his means and the procurement of my uncle, that I was kidnapped within sight of this town, carried to sea, suffered shipwreck and a hundred other hardships, and stand before you to-day in this poor accoutrement.”

“You say you were shipwrecked,” said Rankeillor; “where was that?”

“Off the south end of the Isle of Mull,” said I. “The name of the isle on which I was cast up is the Island Earraid.”

“Ah!” says he, smiling, “you are deeper than me in the geography. But so far, I may tell you, this agrees pretty exactly with other informations that I hold. But you say you were kidnapped; in what sense?”

“In the plain meaning of the word, sir,” said I. “I was on my way to your house, when I was trepanned on board the brig, cruelly struck down, thrown below, and knew no more of anything till we were far at sea. I was destined for the plantations; a fate that, in God’s providence, I have escaped.”

“The brig was lost on June the 27th,” says he, looking in his book, “and we are now at August the 24th. Here is a considerable hiatus, Mr. Balfour, of near upon two months. It has already caused a vast amount of trouble to your friends; and I own I shall not be very well contented until it is set right.”

“Indeed, sir,” said I, “these months are very easily filled up; but yet before I told my story, I would be glad to know that I was talking to a friend.”

“This is to argue in a circle,” said the lawyer. “I cannot be convinced till I have heard you. I cannot be your friend till I am properly informed. If you were more trustful, it would better befit your time of life. And you know, Mr. Balfour, we have a proverb in the country that evil-doers are aye evil-dreaders.”

“You are not to forget, sir,” said I, “that I have already suffered by my trustfulness; and was shipped off to be a slave by the very man that (if I rightly understand) is your employer?”

All this while I had been gaining ground with Mr. Rankeillor, and in proportion as I gained ground, gaining confidence. But at this sally, which I made with something of a smile myself, he fairly laughed aloud.

“No, no,” said he, “it is not so bad as that. Fui, non sum. I was indeed your uncle’s man of business; but while you (imberbis juvenis custode remoto) were gallivanting in the west, a good deal of water has run under the bridges; and if your ears did not sing, it was not for lack of being talked about. On the very day of your sea disaster, Mr. Campbell stalked into my office, demanding you from all the winds. I had never heard of your existence; but I had known your father; and from matters in my competence (to be touched upon hereafter) I was disposed to fear the worst. Mr. Ebenezer admitted having seen you; declared (what seemed improbable) that he had given you considerable sums; and that you had started for the continent of Europe, intending to fulfil your education, which was probable and praiseworthy. Interrogated how you had come to send no word to Mr. Campbell, he deponed that you had expressed a great desire to break with your past life. Further interrogated where you now were, protested ignorance, but believed you were in Leyden. That is a close sum of his replies. I am not exactly sure that any one believed him,” continued Mr. Rankeillor with a smile; “and in particular he so much disrelished me expressions of mine that (in a word) he showed me to the door. We were then at a full stand; for whatever shrewd suspicions we might entertain, we had no shadow of probation. In the very article, comes Captain Hoseason with the story of your drowning; whereupon all fell through; with no consequences but concern to Mr. Campbell, injury to my pocket, and another blot upon your uncle’s character, which could very ill afford it. And now, Mr. Balfour,” said he, “you understand the whole process of these matters, and can judge for yourself to what extent I may be trusted.”

Indeed he was more pedantic than I can represent him, and placed more scraps of Latin in his speech; but it was all uttered with a fine geniality of eye and manner which went far to conquer my distrust.

Comments (0)