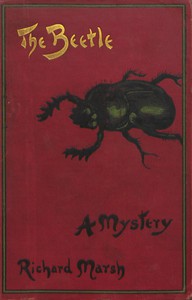

The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (large screen ebook reader TXT) 📕

Read free book «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (large screen ebook reader TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Richard Marsh

Read book online «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (large screen ebook reader TXT) 📕». Author - Richard Marsh

‘Did you acquaint your father with the addition to his household?’

She looked at me, quizzically.

‘You see, when one has such a father as mine one cannot tell him everything, at once. There are occasions on which one requires time.’

I felt that this would be wholesome hearing for old Lindon.

‘Last night, after papa and I had exchanged our little courtesies,—which, it is to be hoped, were to papa’s satisfaction, since they were not to be mine—I went to see the patient. I was told that he had neither eaten nor drunk, moved nor spoken. But, so soon as I approached his bed, he showed signs of agitation. He half raised himself upon his pillow, and he called out, as if he had been addressing some large assembly—I can’t describe to you the dreadful something which was in his voice, and on his face,—“Paul Lessingham!—Beware!—The Beetle!”’

When she said that, I was startled.

‘Are you sure those were the words he used?’

‘Quite sure. Do you think I could mistake them,—especially after what has happened since? I hear them singing in my ears,—they haunt me all the time.’

She put her hands up to her face, as if to veil something from her eyes. I was becoming more and more convinced that there was something about the Apostle’s connection with his Oriental friend which needed probing to the bottom.

‘What sort of a man is he to look at, this patient of yours?’

I had my doubts as to the gentleman’s identity,—which her words dissolved; only, however, to increase my mystification in another direction.

‘He seems to be between thirty and forty. He has light hair, and straggling sandy whiskers. He is so thin as to be nothing but skin and bone,—the doctor says it’s a case of starvation.’

‘You say he has light hair, and sandy whiskers. Are you sure the whiskers are real?’

She opened her eyes.

‘Of course they’re real. Why shouldn’t they be real?’

‘Does he strike you as being a—foreigner?’

‘Certainly not. He looks like an Englishman, and he speaks like one, and not, I should say, of the lowest class. It is true that there is a very curious, a weird, quality in his voice, what I have heard of it, but it is not un-English. If it is catalepsy he is suffering from, then it is a kind of catalepsy I never heard of. Have you ever seen a clairvoyant?’ I nodded. ‘He seems to me to be in a state of clairvoyance. Of course the doctor laughed when I told him so, but we know what doctors are, and I still believe that he is in some condition of the kind. When he said that last night he struck me as being under what those sort of people call ‘influence,’ and that whoever had him under influence was forcing him to speak against his will, for the words came from his lips as if they had been wrung from him in agony.’

Knowing what I did know, that struck me as being rather a remarkable conclusion for her to have reached, by the exercise of her own unaided powers of intuition,—but I did not choose to let her know I thought so.

‘My dear Marjorie!—you who pride yourself on having your imagination so strictly under control!—on suffering it to take no errant flights!’

‘Is not the fact that I do so pride myself proof that I am not likely to make assertions wildly,—proof, at any rate, to you? Listen to me. When I left that unfortunate creature’s room,—I had had a nurse sent for, I left him in her charge—and reached my own bedroom, I was possessed by a profound conviction that some appalling, intangible, but very real danger, was at that moment threatening Paul.’

‘Remember,—you had had an exciting evening; and a discussion with your father. Your patient’s words came as a climax.’

‘That is what I told myself,—or, rather, that was what I tried to tell myself; because, in some extraordinary fashion, I had lost the command of my powers of reflection.’

‘Precisely.’

‘It was not precisely,—or, at least, it was not precisely in the sense you mean. You may laugh at me, Sydney, but I had an altogether indescribable feeling, a feeling which amounted to knowledge, that I was in the presence of the supernatural.’

‘Nonsense!’

‘It was not nonsense,—I wish it had been nonsense. As I have said, I was conscious, completely conscious, that some frightful peril was assailing Paul. I did not know what it was, but I did know that it was something altogether awful, of which merely to think was to shudder. I wanted to go to his assistance, I tried to, more than once; but I couldn’t, and I knew that I couldn’t,—I knew that I couldn’t move as much as a finger to help him.—Stop,—let me finish!—I told myself that it was absurd, but it wouldn’t do; absurd or not, there was the terror with me in the room. I knelt down, and I prayed, but the words wouldn’t come. I tried to ask God to remove this burden from my brain, but my longings wouldn’t shape themselves into words, and my tongue was palsied. I don’t know how long I struggled, but, at last, I came to understand that, for some cause, God had chosen to leave me to fight the fight alone. So I got up, and undressed, and went to bed,—and that was the worst of all. I had sent my maid away in the first rush of my terror, afraid, and, I think, ashamed, to let her see my fear. Now I would have given anything to summon her back again, but I couldn’t do it, I couldn’t even ring the bell. So, as I say, I got into bed.’

She paused, as if to collect her thoughts. To listen to her words, and to think of the suffering which they meant to her, was almost more than I could endure. I would have thrown away the world to have been able to take her in my arms, and soothe her fears. I knew her to be, in general, the least hysterical of young women; little wont to become the prey of mere delusions; and, incredible though it sounded, I had an innate conviction that, even in its wildest periods, her story had some sort of basis in solid fact. What that basis amounted to, it would be my business, at any and every cost, quickly to determine.

‘You know how you have always laughed at me because of my objection to—cockroaches, and how, in spring, the neighbourhood of May-bugs has always made me uneasy. As soon as I got into bed I felt that something of the kind was in the room.’

‘Something of what kind?’

‘Some kind of—beetle. I could hear the whirring of its wings; I could hear its droning in the air; I knew that it was hovering above my head; that it was coming lower and lower, nearer and nearer. I hid myself; I covered myself all over with the clothes,—then I felt it bumping against the coverlet. And, Sydney!’ She drew closer. Her blanched cheeks and frightened eyes made my heart bleed. Her voice became but an echo of itself. ‘It followed me.’

‘Marjorie!’

‘It got into the bed.’

‘You imagined it.’

‘I didn’t imagine it. I heard it crawl along the sheets, till it found a way between them, and then it crawled towards me. And I felt it—against my face.—And it’s there now.’

‘Where?’

She raised the forefinger of her left hand.

‘There!—Can’t you hear it droning?’

She listened, intently. I listened too. Oddly enough, at that instant the droning of an insect did become audible.

‘It’s only a bee, child, which has found its way through the open window.’

‘I wish it were only a bee, I wish it were.—Sydney, don’t you feel as if you were in the presence of evil? Don’t you want to get away from it, back into the presence of God?’

‘Marjorie!’

‘Pray, Sydney, pray!—I can’t!—I don’t know why, but I can’t!

She flung her arms about my neck, and pressed herself against me in paroxysmal agitation. The violence of her emotion bade fair to unman me too. It was so unlike Marjorie,—and I would have given my life to save her from a toothache. She kept repeating her own words,—as if she could not help it.

‘Pray, Sydney, pray!’

At last I did as she wished me. At least, there is no harm in praying,—I never heard of its bringing hurt to anyone. I repeated aloud the Lord’s Prayer,—the first time for I know not how long. As the divine sentences came from my lips, hesitatingly enough, I make no doubt, her tremors ceased. She became calmer. Until, as I reached the last great petition, ‘Deliver us from evil,’ she loosed her arms from about my neck, and dropped upon her knees, close to my feet. And she joined me in the closing words, as a sort of chorus.

‘For Thine is the Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory, for ever and ever. Amen.’

When the prayer was ended, we both of us were still. She with her head bowed, and her hands clasped; and I with something tugging at my heart-strings which I had not felt there for many and many a year, almost as if it had been my mother’s hand;—I daresay that sometimes she does stretch out her hand, from her place among the angels, to touch my heart-strings, and I know nothing of it all the while.

As the silence still continued, I chanced to glance up, and there was old Lindon peeping at us from his hiding-place behind the screen. The look of amazed perplexity which was on his big red face struck me with such a keen sense of the incongruous that it was all I could do to keep from laughter. Apparently the sight of us did nothing to lighten the fog which was in his brain, for he stammered out, in what was possibly intended for a whisper,

‘Is—is she m-mad?’

The whisper,—if it was meant for a whisper—was more than sufficiently audible to catch his daughter’s ears. She started—raised her head—sprang to her feet—turned—and saw her father.

‘Papa!’

Immediately her sire was seized with an access of stuttering.

‘W-w-what the d-devil’s the—the m-m-meaning of this?’

Her utterance was clear enough,—I fancy her parent found it almost painfully clear.

‘Rather it is for me to ask, what is the meaning of this! Is it possible, that, all the time, you have actually been concealed behind that—screen?’

Unless I am mistaken the old gentleman cowered before the directness of his daughter’s gaze,—and endeavoured to conceal the fact by an explosion of passion.

Do-don’t you s-speak to me li-like that, you un-undutiful girl! I—I’m your father!’

‘You certainly are my father; though I was unaware until now that my father was capable of playing the part of eavesdropper.’

Rage rendered him speechless,—or, at any rate, he chose to let us believe that that was the determining cause of his continuing silent. So Marjorie turned to me,—and, on the whole, I had rather she had not. Her manner was very different from what it had been just now,—it was more than civil, it was freezing.

‘Am I to understand, Mr Atherton, that this has been done with your cognisance? That while you suffered me to pour out my heart to you unchecked, you were aware, all the time, that there was a listener behind the screen?’

I became keenly aware, on a sudden, that I had borne my share in playing her a very shabby trick,—I should have liked to throw old Lindon through the window.

‘The thing was not of my contriving. Had I had the opportunity I would have compelled Mr Lindon to face you when you came in. But your distress caused me to lose my balance. And you will do me the justice to remember that I endeavoured to induce you to come with me into another room.’

‘But I do not seem to remember your hinting at there being any particular reason why I should have gone.’

‘You never gave me a chance.’

‘Sydney!—I had not thought you would have played me such a trick!’

When she said that—in such a tone!—the woman whom I loved!—I could have hammered my head against the wall. The hound I was to have treated her so scurvily!

Perceiving I was crushed she turned again to face her father, cool, calm, stately;—she was, on a sudden, once more, the Marjorie with whom I was familiar. The demeanour of parent and child was in

Comments (0)