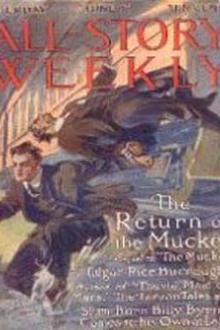

The Return of the Mucker by Edgar Rice Burroughs (top inspirational books TXT) 📕

Billy was the first upon the platform. He was the first to see the open door. It meant one of two things--a chance to escape, or, death. Even the latter was to be preferred to life imprisonment.

Billy did not hesitate an instant. Even before the deputy sheriff realized that the door was open, his prisoner had leaped from the moving train dragging his guard after him.

CHAPTER II

THE ESCAPE

BYRNE had no time to pick any particular spot to jump for. When he did jump he might have been directly over a picket fence, or a bottomless pit--he did not know. Nor did he care.

As it happened he was ov

Read free book «The Return of the Mucker by Edgar Rice Burroughs (top inspirational books TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Rice Burroughs

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Return of the Mucker by Edgar Rice Burroughs (top inspirational books TXT) 📕». Author - Edgar Rice Burroughs

For an hour Billy neither saw nor heard any sign of the enemy, though several times he raised his hat above the breastwork upon the muzzle of his carbine to draw their fire.

It was midafternoon when the sound of distant rifle fire came faintly to the ears of the two men from somewhere far below them.

“The boys must be comin’,” whispered Eddie Shorter hopefully.

For half an hour the firing continued and then silence again fell upon the mountains. Eddie began to wander mentally. He talked much of Kansas and his old home, and many times he begged for water.

“Buck up, kid,” said Billy; “the boys’ll be along in a minute now an’ then we’ll get you all the water you want.”

But the boys did not come. Billy was standing up now, stretching his legs, and searching up and down the canyon for Indians. He was wondering if he could chance making a break for the valley where they stood some slight chance of meeting with their companions, and even as he considered the matter seriously there came a staccato report and Billy Byrne fell forward in a heap.

“God!” cried Eddie. “They got him now, they got him.”

Byrne stirred and struggled to rise.

“Like’ll they got me,” he said, and staggered to his knees.

Over the breastwork he saw a half-dozen Indians running rapidly toward the shelter—he saw them in a haze of red that was caused not by blood but by anger. With an oath Billy Byrne leaped to his feet. From his knees up his whole body was exposed to the enemy; but Billy cared not. He was in a berserker rage. Whipping his carbine to his shoulder he let drive at the advancing Indians who were now beyond hope of cover. They must come on or be shot down where they were, so they came on, yelling like devils and stopping momentarily to fire upon the rash white man who stood so perfect a target before them.

But their haste spoiled their marksmanship. The bullets zinged and zipped against the rocky little fortress, they nicked Billy’s shirt and trousers and hat, and all the while he stood there pumping lead into his assailants—not hysterically; but with the cool deliberation of a butcher slaughtering beeves.

One by one the Pimans dropped until but a single Indian rushed frantically upon the white man, and then the last of the assailants lunged forward across the breastwork with a bullet from Billy’s carbine through his forehead.

Eddie Shorter had raised himself painfully upon an elbow that he might witness the battle, and when it was over he sank back, the blood welling from between his set teeth.

Billy turned to look at him when the last of the Pimans was disposed of, and seeing his condition kneeled beside him and took his head in the hollow of an arm.

“You orter lie still,” he cautioned the Kansan. “Tain’t good for you to move around much.”

“It was worth it,” whispered Eddie. “Say, but that was some scrap. You got your nerve standin’ up there against the bunch of ‘em; but if you hadn’t they’d have rushed us and some of ‘em would a-got in.”

“Funny the boys don’t come,” said Billy.

“Yes,” replied Eddie, with a sigh; “it’s milkin’ time now, an’ I figgered on goin’ to Shawnee this evenin’. Them’s nice cookies, maw. I—”

Billy Byrne was bending low to catch his feeble words, and when the voice trailed out into nothingness he lowered the tousled red head to the hard earth and turned away.

Could it be that the thing which glistened on the eyelid of the toughest guy on the West Side was a tear?

The afternoon waned and night came, but it brought to Billy Byrne neither renewed attack nor succor. The bullet which had dropped him momentarily had but creased his forehead. Aside from the fact that he was blood covered from the wound it had inconvenienced him in no way, and now that darkness had fallen he commenced to plan upon leaving the shelter.

First he transferred Eddie’s ammunition to his own person, and such valuables and trinkets as he thought “maw” might be glad to have, then he removed the breechblock from Eddie’s carbine and stuck it in his pocket that the weapon might be valueless to the Indians when they found it.

“Sorry I can’t bury you old man,” was Billy’s parting comment, as he climbed over the breastwork and melted into the night.

Billy Byrne moved cautiously through the darkness, and he moved not in the direction of escape and safety but directly up the canyon in the way that the village of the Pimans lay.

Soon he heard the sound of voices and shortly after saw the light of cook fires playing upon bronzed faces and upon the fronts of low huts. Some women were moaning and wailing. Billy guessed that they mourned for those whom his bullets had found earlier in the day. In the darkness of the night, far up among the rough, forbidding mountains it was all very weird and uncanny.

Billy crept closer to the village. Shelter was abundant. He saw no sign of sentry and wondered why they should be so lax in the face of almost certain attack. Then it occurred to him that possibly the firing he and Eddie had heard earlier in the day far down among the foothills might have meant the extermination of the Americans from El Orobo.

“Well, I’ll be next then,” mused Billy, and wormed closer to the huts. His eyes were on the alert every instant, as were his ears; but no sign of that which he sought rewarded his keenest observation.

Until midnight he lay in concealment and all that time the mourners continued their dismal wailing. Then, one by one, they entered their huts, and silence reigned within the village.

Billy crept closer. He eyed each hut with longing, wondering gaze. Which could it be? How could he determine? One seemed little more promising than the others. He had noted those to which Indians had retired. There were three into which he had seen none go. These, then, should be the first to undergo his scrutiny.

The night was dark. The moon had not yet risen. Only a few dying fires cast a wavering and uncertain light upon the scene. Through the shadows Billy Byrne crept closer and closer. At last he lay close beside one of the huts which was to be the first to claim his attention.

For several moments he lay listening intently for any sound which might come from within; but there was none. He crawled to the doorway and peered within. Utter darkness shrouded and hid the interior.

Billy rose and walked boldly inside. If he could see no one within, then no one could see him once he was inside the door. Therefore, so reasoned Billy Byrne, he would have as good a chance as the occupants of the hut, should they prove to be enemies.

He crossed the floor carefully, stopping often to listen. At last he heard a rustling sound just ahead of him. His fingers tightened upon the revolver he carried in his right hand, by the barrel, clublike. Billy had no intention of making any more noise than necessary.

Again he heard a sound from the same direction. It was not at all unlike the frightened gasp of a woman. Billy emitted a low growl, in fair imitation of a prowling dog that has been disturbed.

Again the gasp, and a low: “Go away!” in liquid feminine tones—and in English!

Billy uttered a low: “S-s-sh!” and tiptoed closer. Extending his hands they presently came in contact with a human body which shrank from him with another smothered cry.

“Barbara!” whispered Billy, bending closer.

A hand reached out through the darkness, found him, and closed upon his sleeve.

“Who are you?” asked a low voice.

“Billy,” he replied. “Are you alone in here?”

“No, an old woman guards me,” replied the girl, and at the same time they both heard a movement close at hand, and something scurried past them to be silhouetted for an instant against the path of lesser darkness which marked the location of the doorway.

“There she goes!” cried Barbara. “She heard you and she has gone for help.”

“Then come!” said Billy, seizing the girl’s arm and dragging her to her feet; but they had scarce crossed half the distance to the doorway when the cries of the old woman without warned them that the camp was being aroused.

Billy thrust a revolver into Barbara’s hand. “We gotta make a fight of it, little girl,” he said. “But you’d better die than be here alone.”

As they emerged from the hut they saw warriors running from every doorway. The old woman stood screaming in Piman at the top of her lungs. Billy, keeping Barbara in front of him that he might shield her body with his own, turned directly out of the village. He did not fire at first hoping that they might elude detection and thus not draw the fire of the Indians upon them; but he was doomed to disappointment, and they had taken scarcely a dozen steps when a rifle spoke above the noise of human voices and a bullet whizzed past them.

Then Billy replied, and Barbara, too, from just behind his shoulder. Together they backed away toward the shadow of the trees beyond the village and as they went they poured shot after shot into the village.

The Indians, but just awakened and still half stupid from sleep, did not know but that they were attacked by a vastly superior force, and this fear held them in check for several minutes—long enough for Billy and Barbara to reach the summit of the bluff from which Billy and Eddie had first been fired upon.

Here they were hidden from the view of the Indians, and Billy broke at once into a run, half carrying the girl with a strong arm about her waist.

“If we can reach the foothills,” he said, “I think we can dodge ‘em, an’ by goin’ all night we may reach the river and El Orobo by morning. It’s a long hike, Barbara, but we gotta make it—we gotta, for if daylight finds us in the Piman country we won’t never make it. Anyway,” he concluded optimistically, “it’s all down hill.”

“We’ll make it, Billy,” she replied, “if we can get past the sentry.”

“What sentry?” asked Billy. “I didn’t see no sentry when I come in.”

“They keep a sentry way down the trail all night,” replied the girl. “In the daytime he is nearer the village—on the top of this bluff, for from here he can see the whole valley; but at night they station him farther away in a narrow part of the trail.”

“It’s a mighty good thing you tipped me off,” said Billy; “for I’d a-run right into him. I thought they was all behind us now.”

After that they went more cautiously, and when they reached the part of the trail where the sentry might be expected to be found, Barbara warned Billy of the fact. Like two thieves they crept along in the shadow of the canyon wall. Inwardly Billy cursed the darkness of the night which hid from view everything more than a few paces from them; yet it may have been this very darkness which saved them, since it hid them as effectually from an enemy as it hid the enemy from them. They had reached the point where Barbara was positive the sentry should be. The girl was clinging tightly to Billy’s left arm. He could feel the pressure of her fingers as they sunk into his muscles, sending little tremors and thrills through his giant frame. Even in the face of death Billy

Comments (0)