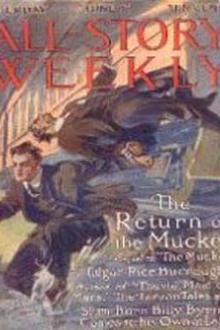

The Return of the Mucker by Edgar Rice Burroughs (top inspirational books TXT) 📕

Billy was the first upon the platform. He was the first to see the open door. It meant one of two things--a chance to escape, or, death. Even the latter was to be preferred to life imprisonment.

Billy did not hesitate an instant. Even before the deputy sheriff realized that the door was open, his prisoner had leaped from the moving train dragging his guard after him.

CHAPTER II

THE ESCAPE

BYRNE had no time to pick any particular spot to jump for. When he did jump he might have been directly over a picket fence, or a bottomless pit--he did not know. Nor did he care.

As it happened he was ov

Read free book «The Return of the Mucker by Edgar Rice Burroughs (top inspirational books TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Edgar Rice Burroughs

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Return of the Mucker by Edgar Rice Burroughs (top inspirational books TXT) 📕». Author - Edgar Rice Burroughs

That was the last Sergeant Flannagan had seen either of Billy Byrne or his companion. The trail had ceased at the open window of the washroom at the rear of the restaurant, and search as he would be had been unable to pick it up again.

No one in Kansas City had seen two men that night answering the descriptions Flannagan had been able to give— at least no one whom Flannagan could unearth.

Finally he had been forced to take the Kansas City chief into his confidence, and already a dozen men were scouring such sections of Kansas City in which it seemed most likely an escaped murderer would choose to hide.

Flannagan had been out himself for a while; but now he was in to learn what progress, if any, had been made. He had just learned that three suspects had been arrested and was waiting to have them paraded before him.

When the door swung in and the three were escorted into his presence Sergeant Flannagan gave a snort of disgust, indicative probably not only of despair; but in a manner registering his private opinion of the mental horse power and efficiency of the Kansas City sleuths, for of the three one was a pasty-faced, chestless youth, even then under the influence of cocaine, another was an old, bewhiskered hobo, while the third was unquestionably a Chinaman.

Even professional courtesy could scarce restrain Sergeant Flannagan’s desire toward bitter sarcasm, and he was upon the point of launching forth into a vitriolic arraignment of everything west of Chicago up to and including, specifically, the Kansas City detective bureau, when the telephone bell at the chief’s desk interrupted him. He had wanted the chief to hear just what he thought, so he waited.

The chief listened for a few minutes, asked several questions and then, placing a fat hand over the transmitter, he wheeled about toward Flannagan.

“Well,” he said, “I guess I got something for you at last. There’s a bo on the wire that says he’s just seen your man down near Shawnee. He wants to know if you’ll split the reward with him.”

Flannagan yawned and stretched.

“I suppose,” he said, ironically, “that if I go down there I’ll find he’s corraled a nigger,” and he looked sorrowfully at the three specimens before him.

“I dunno,” said the chief. “This guy says he knows Byrne well, an’ that he’s got it in for him. Shall I tell him you’ll be down—and split the reward?”

“Tell him I’ll be down and that I’ll treat him right,” replied Flannagan, and after the chief had transmitted the message, and hung up the receiver: “Where is this here Shawnee, anyhow?”

“I’ll send a couple of men along with you. It isn’t far across the line, an’ there won’t be no trouble in getting back without nobody knowin’ anything about it—if you get him.”

“All right,” said Flannagan, his visions of five hundred already dwindled to a possible one.

It was but a little past one o’clock that a touring car rolled south out of Kansas City with Detective Sergeant Flannagan in the front seat with the driver and two burly representatives of Missouri law in the back.

WHEN the two tramps approached the farmhouse at which Billy had purchased food a few hours before the farmer’s wife called the dog that was asleep in the summer kitchen and took a shotgun down from its hook beside the door.

From long experience the lady was a reader of character— of hobo character at least—and she saw nothing in the appearance of either of these two that inspired even a modicum of confidence. Now the young fellow who had been there earlier in the day and who, wonder of wonders, had actually paid for the food she gave him, had been of a different stamp. His clothing had proclaimed him a tramp, but, thanks to the razor Bridge always carried, he was clean shaven. His year of total abstinence had given him clear eyes and a healthy skin. There was a freshness and vigor in his appearance and carriage that inspired confidence rather than suspicion.

She had not mistrusted him; but these others she did mistrust. When they asked to use the telephone she refused and ordered them away, thinking it but an excuse to enter the house; but they argued the matter, explaining that they had discovered an escaped murderer hiding near—by—in fact in her own meadow—and that they wished only to call up the Kansas City police.

Finally she yielded, but kept the dog by her side and the shotgun in her hand while the two entered the room and crossed to the telephone upon the opposite side.

From the conversation which she overheard the woman concluded that, after all, she had been mistaken, not only about these two, but about the young man who had come earlier in the day and purchased food from her, for the description the tramp gave of the fugitive tallied exactly with that of the young man.

It seemed incredible that so honest looking a man could be a murderer. The good woman was shocked, and not a little unstrung by the thought that she had been in the house alone when he had come and that if he had wished to he could easily have murdered her.

“I hope they get him,” she said, when the tramp had concluded his talk with Kansas City. “It’s awful the carryings on they is nowadays. Why a body can’t never tell who to trust, and I thought him such a nice young man. And he paid me for what he got, too.”

The dog, bored by the inaction, had wandered back into the summer kitchen and resumed his broken slumber. One of the tramps was leaning against the wall talking with the farmer woman. The other was busily engaged in scratching his right shin with what remained of the heel of his left shoe. He supported himself with one hand on a small table upon the top of which was a family Bible.

Quite unexpectedly he lost his balance, the table tipped, he was thrown still farther over toward it, and all in the flash of an eye tramp, table, and family Bible crashed to the floor.

With a little cry of alarm the woman rushed forward to gather up the Holy Book, in her haste forgetting the shotgun and leaving it behind her leaning against the arm of a chair.

Almost simultaneously the two tramps saw the real cause of her perturbation. The large book had fallen upon its back, open; and as several of the leaves turned over before coming to rest their eyes went wide at what was revealed between.

United States currency in denominations of five, ten, and twenty-dollar bills lay snugly inserted between the leaves of the Bible. The tramp who lay on the floor, as yet too surprised to attempt to rise, rolled over and seized the book as a football player seizes the pigskin after a fumble, covering it with his body, his arms, and sticking out his elbows as a further protection to the invaluable thing.

At the first cry of the woman the dog rose, growling, and bounded into the room. The tramp leaning against the wall saw the brute coming—a mongrel hound-dog, bristling and savage.

The shotgun stood almost within the man’s reach—a step and it was in his hands. As though sensing the fellow’s intentions the dog wheeled from the tramp upon the floor, toward whom he had leaped, and sprang for the other ragged scoundrel.

The muzzle of the gun met him halfway. There was a deafening roar. The dog collapsed to the floor, his chest torn out. Now the woman began to scream for help; but in an instant both the tramps were upon her choking her to silence.

One of them ran to the summer kitchen, returning a moment later with a piece of clothesline, while the other sat astride the victim, his fingers closed about her throat. Once he released his hold and she screamed again. Presently she was secured and gagged. Then the two commenced to rifle the Bible.

Eleven hundred dollars in bills were hidden there, because the woman and her husband didn’t believe in banks—the savings of a lifetime. In agony, as she regained consciousness, she saw the last of their little hoard transferred to the pockets of the tramps, and when they had finished they demanded to know where she kept the rest, loosening her gag that she might reply.

She told them that that was all the money she had in the world, and begged them not to take it.

“Youse’ve got more coin dan dis,” growled one of the men, “an’ youse had better pass it over, or we’ll find a way to make youse.”

But still she insisted that that was all. The tramp stepped into the kitchen. A wood fire was burning in the stove. A pair of pliers lay upon the window sill. With these he lifted one of the hot stove-hole covers and returned to the parlor, grinning.

“I guess she’ll remember she’s got more wen dis begins to woik,” he said. “Take off her shoes, Dink.”

The other growled an objection.

“Yeh poor boob,” he said. “De dicks’ll be here in a little while. We’d better be makin’ our getaway wid w’at we got.”

“Gee!” exclaimed his companion. “I clean forgot all about de dicks,” and then after a moment’s silence during which his evil face underwent various changes of expression from fear to final relief, he turned an ugly, crooked grimace upon his companion.

“We got to croak her,” he said. “Dey ain’t no udder way. If dey finds her alive she’ll blab sure, an’ dey won’t be no trouble ‘bout gettin’ us or identifyin’ us neither.”

The other shrugged.

“Le’s beat it,” he whined. “We can’t more’n do time fer dis job if we stop now; but de udder’ll mean—” and he made a suggestive circle with a grimy finger close to his neck.

“No it won’t nothin’ of de kind,” urged his companion. “I got it all doped out. We got lots o’ time before de dicks are due. We’ll croak de skirt, an’ den we’ll beat it up de road AN’ MEET DE DICKS—see?”

The other was aghast.

“Wen did youse go nuts?” he asked.

“I ain’t gone nuts. Wait ‘til I gets t’rough. We meets de dicks, innocent-like; but first we caches de dough in de woods. We tells ‘em we hurried right on to lead ‘em to dis Byrne guy, an’ wen we gets back here to de farmhouse an’ finds wot’s happened here we’ll be as flabbergasted as dey be.”

“Oh, nuts!” exclaimed the other disgustedly. “Youse don’t tink youse can put dat over on any wise guy from Chi, do youse? Who will dey tink croaked de old woman an’ de ki-yi? Will dey tink dey kilt deyreselves?”

“Dey’ll tink Byrne an’ his pardner croaked ‘em, you simp,” replied Crumb.

Dink scratched his head, and as the possibilities of the scheme filtered into his dull brain a broad grin bared his yellow teeth.

“You’re dere, pal,” he exclaimed, real admiration in his tone. “But who’s goin’ to do it?”

“I’ll do it,” said Crumb. “Dere ain’t no chanct of gettin’ in bad for it, so I jest as soon do the job. Get me a knife, or an ax from de kitchen—de gat makes too much noise.”

Something awoke Billy Byrne with a start. Faintly, in the back of his consciousness, the dim suggestion of a loud noise still reverberated. He sat up and looked about him.

“I wonder

Comments (0)