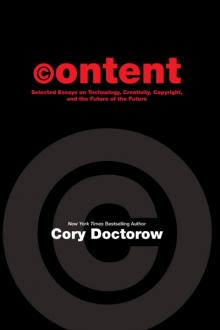

Content by Cory Doctorow (first e reader txt) 📕

And so it has been for the last 13 years. The companies that claim the ability to regulate humanity's Right to Know have been tireless in their endeavors to prevent the inevitable. The won most of the legislative battles in the U.S. and abroad, having purchased all the government money could buy. They even won most of the contests in court. They created digital rights management software schemes that behaved rather like computer viruses.

Indeed, they did about everything they could short of seriously examining the actual economics of the situation - it has never been proven to me that illegal downloads are more like shoplifted goods than viral marketing - or trying to come up with a business model that the market might embrace.

Had it been left to the stewardship of the usual suspects, there would scarcely be a word or a note online that you didn't have to pay to experience. There would be increasingly little free speech or any consequence, since free speech is not something anyone can o

Read free book «Content by Cory Doctorow (first e reader txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Cory Doctorow

- Performer: 1892391813

Read book online «Content by Cory Doctorow (first e reader txt) 📕». Author - Cory Doctorow

Taken more broadly, this kind of metadata can be thought of as a pedigree: who thinks that this document is valuable? How closely correlated have this person’s value judgments been with mine in times gone by? This kind of implicit endorsement of information is a far better candidate for an information-retrieval panacea than all the world’s schema combined.

$$$$

Amish for QWERTY

(Originally published on the O’Reilly Network, 07/09/2003)

I learned to type before I learned to write. The QWERTY keyboard layout is hard-wired to my brain, such that I can’t write anything of significance without that I have a 101-key keyboard in front of me. This has always been a badge of geek pride: unlike the creaking pen-and-ink dinosaurs that I grew up reading, I’m well adapted to the modern reality of technology. There’s a secret elitist pride in touch-typing on a laptop while staring off into space, fingers flourishing and caressing the keys.

But last week, my pride got pricked. I was brung low by a phone. Some very nice people from Nokia loaned me a very latest-and-greatest cameraphone, the kind of gadget I’ve described in my science fiction stories. As I prodded at the little 12-key interface, I felt like my father, a 60s-vintage computer scientist who can’t get his wireless network to work, must feel. Like a creaking dino. Like history was passing me by. I’m 31, and I’m obsolete. Or at least Amish.

People think the Amish are technophobes. Far from it. They’re ideologues. They have a concept of what right-living consists of, and they’ll use any technology that serves that ideal — and mercilessly eschew any technology that would subvert it. There’s nothing wrong with driving the wagon to the next farm when you want to hear from your son, so there’s no need to put a phone in the kitchen. On the other hand, there’s nothing right about your livestock dying for lack of care, so a cellphone that can call the veterinarian can certainly find a home in the horse barn.

For me, right-living is the 101-key, QWERTY, computer-centric mediated lifestyle. It’s having a bulky laptop in my bag, crouching by the toilets at a strange airport with my AC adapter plugged into the always-awkwardly-placed power source, running software that I chose and installed, communicating over the wireless network. I use a network that has no incremental cost for communication, and a device that lets me install any software without permission from anyone else. Right-living is the highly mutated, commodity-hardware- based, public and free Internet. I’m QWERTY-Amish, in other words.

I’m the kind of perennial early adopter who would gladly volunteer to beta test a neural interface, but I find myself in a moral panic when confronted with the 12-button keypad on a cellie, even though that interface is one that has been greedily adopted by billions of people worldwide, from strap-hanging Japanese schoolgirls to Kenyan electoral scrutineers to Filipino guerrillas in the bush. The idea of paying for every message makes my hackles tumesce and evokes a reflexive moral conviction that text-messaging is inherently undemocratic, at least compared to free-as-air email. The idea of only running the software that big-brother telco has permitted me on my handset makes me want to run for the hills.

The thumb-generation who can tap out a text-message under their desks while taking notes with the other hand — they’re in for it, too. The pace of accelerated change means that we’re all of us becoming wed to interfaces — ways of communicating with our tools and our world — that are doomed, doomed, doomed. The 12-buttoners are marrying the phone company, marrying a centrally controlled network that requires permission to use and improve, a Stalinist technology whose centralized choke points are subject to regulation and the vagaries of the telcos. Long after the phone companies have been outcompeted by the pure and open Internet (if such a glorious day comes to pass), the kids of today will be bound by its interface and its conventions.

The sole certainty about the future is its Amishness. We will all bend our brains to suit an interface that we will either have to abandon or be left behind. Choose your interface — and the values it implies — carefully, then, before you wed your thought processes to your fingers’ dance. It may be the one you’re stuck with.

$$$$

Ebooks: Neither E, Nor Books

(Paper for the O’Reilly Emerging Technologies Conference, San Diego, February 12, 2004)

Forematter:

This talk was initially given at the O’Reilly Emerging Technology Conference [ http://conferences.oreillynet.com/et2004/ ], along with a set of slides that, for copyright reasons (ironic!) can’t be released alongside of this file. However, you will find, interspersed in this text, notations describing the places where new slides should be loaded, in [square-brackets].

For starters, let me try to summarize the lessons and intuitions I’ve had about ebooks from my release of two novels and most of a short story collection online under a Creative Commons license. A parodist who published a list of alternate titles for the presentations at this event called this talk, “eBooks Suck Right Now,” [eBooks suck right now] and as funny as that is, I don’t think it’s true.

No, if I had to come up with another title for this talk, I’d call it: “Ebooks: You’re Soaking in Them.” [Ebooks: You’re Soaking in Them] That’s because I think that the shape of ebooks to come is almost visible in the way that people interact with text today, and that the job of authors who want to become rich and famous is to come to a better understanding of that shape.

I haven’t come to a perfect understanding. I don’t know what the future of the book looks like. But I have ideas, and I’ll share them with you:

1. Ebooks aren’t marketing. [Ebooks aren’t marketing] OK, so ebooks are marketing: that is to say that giving away ebooks sells more books. Baen Books, who do a lot of series publishing, have found that giving away electronic editions of the previous installments in their series to coincide with the release of a new volume sells the hell out of the new book — and the backlist. And the number of people who wrote to me to tell me about how much they dug the ebook and so bought the paper-book far exceeds the number of people who wrote to me and said, “Ha, ha, you hippie, I read your book for free and now I’m not gonna buy it.” But ebooks shouldn’t be just about marketing: ebooks are a goal unto themselves. In the final analysis, more people will read more words off more screens and fewer words off fewer pages and when those two lines cross, ebooks are gonna have to be the way that writers earn their keep, not the way that they promote the dead-tree editions.

2. Ebooks complement paper books. [Ebooks complement paper books]. Having an ebook is good. Having a paper book is good. Having both is even better. One reader wrote to me and said that he read half my first novel from the bound book, and printed the other half on scrap-paper to read at the beach. Students write to me to say that it’s easier to do their term papers if they can copy and paste their quotations into their word-processors. Baen readers use the electronic editions of their favorite series to build concordances of characters, places and events.

3. Unless you own the ebook, you don’t 0wn the book [Unless you own the ebook, you don’t 0wn the book]. I take the view that the book is a “practice” — a collection of social and economic and artistic activities — and not an “object.” Viewing the book as a “practice” instead of an object is a pretty radical notion, and it begs the question: just what the hell is a book? Good question. I write all of my books in a text-editor [TEXT EDITOR SCREENGRAB] (BBEdit, from Barebones Software — as fine a text-editor as I could hope for). From there, I can convert them into a formatted two-column PDF [TWO-UP SCREENGRAB]. I can turn them into an HTML file [BROWSER SCREENGRAB]. I can turn them over to my publisher, who can turn them into galleys, advanced review copies, hardcovers and paperbacks. I can turn them over to my readers, who can convert them to a bewildering array of formats [DOWNLOAD PAGE SCREENGRAB]. Brewster Kahle’s Internet Bookmobile can convert a digital book into a four-color, full-bleed, perfect-bound, laminated-cover, printed-spine paper book in ten minutes, for about a dollar. Try converting a paper book to a PDF or an html file or a text file or a RocketBook or a printout for a buck in ten minutes! It’s ironic, because one of the frequently cited reasons for preferring paper to ebooks is that paper books confer a sense of ownership of a physical object. Before the dust settles on this ebook thing, owning a paper book is going to feel less like ownership than having an open digital edition of the text.

4. Ebooks are a better deal for writers. [Ebooks are a better deal for writers] The compensation for writers is pretty thin on the ground. Amazing Stories, Hugo Gernsback’s original science fiction magazine, paid a couple cents a word. Today, science fiction magazines pay…a couple cents a word. The sums involved are so minuscule, they’re not even insulting: they’re quaint and historical, like the WHISKEY 5 CENTS sign over the bar at a pioneer village. Some writers do make it big, but they’re rounding errors as compared to the total population of sf writers earning some of their living at the trade. Almost all of us could be making more money elsewhere (though we may dream of earning a stephenkingload of money, and of course, no one would play the lotto if there were no winners). The primary incentive for writing has to be artistic satisfaction, egoboo, and a desire for posterity. Ebooks get you that. Ebooks become a part of the corpus of human knowledge because they get indexed by search engines and replicated by the hundreds, thousands or millions. They can be googled.

Even better: they level the playing field between writers and trolls. When Amazon kicked off, many writers got their knickers in a tight and powerful knot at the idea that axe-grinding yahoos were filling the Amazon message-boards with ill-considered slams at their work — for, if a personal recommendation is the best way to sell a book, then certainly a personal condemnation is the best way to not sell a book. Today, the trolls are still with us, but now, the readers get to decide for themselves. Here’s a bit of a review of Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom that was recently posted to Amazon by “A reader from Redwood City, CA”:

[QUOTED TEXT]

> I am really not sure what kind of drugs critics are

> smoking, or what kind of payola may be involved. But

> regardless of what Entertainment Weekly says, whatever

> this newspaper or that magazine says, you shouldn’t

> waste your money. Download it for free from Corey’s

> (sic) site, read the first page, and look away in

> disgust — this book is for people who think Dan

> Brown’s Da Vinci Code is great writing.

Back in the old days, this kind of thing would have really pissed me off. Axe-grinding, mouth-breathing yahoos, defaming my good name! My stars and mittens! But take a closer look at that damning passage:

[PULL-QUOTE]

> Download it for free from Corey’s site, read the first

> page

You see that? Hell, this guy

Comments (0)