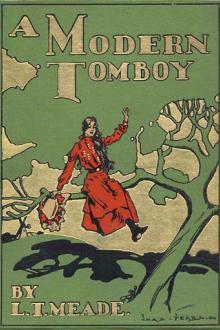

A Modern Tomboy by L. T. Meade (e book reader pc txt) 📕

CHAPTER II.

ROSAMUND TAKES THE LEAD.

Before that day had come to an end, Lucy had discovered how true were Phyllis Flower's words. For Rosamund Cunliffe, without making herself in the least disagreeable, without saying one single rude thing, yet managed to take the lead, and that so effectively that even Lucy herself found that she could not help following in her train.

For instance, after dinner, when the girls--all of them rather tired, and perhaps some of them a little cross, and no one exactly knowing what to do--clustered about the open drawing-room windows, it was Rosamund who proposed that the rugs should be rolled back and that they should have a dance.

Lucy opened her eyes. Nobody before had ever dared to make such a suggestion in the house of Sunnyside. Lucy, it is true, had dancing lessons from a master who came once a week to instruct her and other girls in the winter season, and she had occasionally gone

Read free book «A Modern Tomboy by L. T. Meade (e book reader pc txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: L. T. Meade

- Performer: -

Read book online «A Modern Tomboy by L. T. Meade (e book reader pc txt) 📕». Author - L. T. Meade

Miss Frost, anxious, pale, and miserable, was watching her treasure as she gave a little bit of her heart, at least, first to one girl and then to another, and poor Miss Frost's face looked anything but inviting. Her nose was red, her cheeks pinched and hollow, her eyes somewhat dim. She felt inclined to cry.

Rosamund, however, boldly asked Laura Everett to change places with her, and sat next to Irene.

"Why have they taken Agnes away?" said Irene. "I don't like it. I have a great mind to walk round the table and to snatch her away from those two horrid creatures at the other end, and to bring her to us. Why shouldn't she sit between us? I know she wishes it, poor little darling!"

"We had better leave her alone for the present, Irene; supper won't take long. Don't take any notice. I'll ask Mrs. Merriman to let Agnes sit next to you in future; but don't make a fuss now."

"I hate being good. I don't think I can stand it," said Irene in a most rebellious tone. And then she scowled at Miss Frost in quite her old ferocious way, so that the governess looked more anxious and unhappy than ever. But this was nothing to the scowl she presently gave Lucy Merriman. She fixed her bright eyes on Lucy's face, and not only a frown came between her brows, but the frown was succeeded by a mocking laugh, and then she said in a low tone, which yet was clear as a bell, "I saw you in church one Sunday, and you frightened me so much that I had to go out."

This remark was so strange and unexpected that most of the girls gave utterance to a nervous laugh; but Professor Merriman raised his voice.

"Irene," he said, "that is not at all a polite thing to say. I must have a little talk with you when supper is over, for you are not to say unkind things to your neighbors, or of them, as long as you are in my house."

The firmness of his voice and the dignity of his bearing had a slight effect on Irene. Rosamund began to talk rapidly to her on different subjects, and by and by the meal came to an end.

That evening nothing very extraordinary occurred; but Irene, without waiting for any one, rushed down to the room and seized little Agnes's hand.

"Come, Agnes," she said, "it is time for you to go to bed."

"I am the person who has charge of putting the little ones to bed," said Miss Frost, going up and speaking in a trembling tone.

"You may put all the other little ones to bed, as far as I am concerned," said Irene; "but you don't put my Agnes to bed."

"But she is my Agnes, too."

"No; she is mine. Agnes, say at once that you belong altogether to me; that you are my darling, my doll, my baby."

"I do love you," said little Agnes; "but of course I love Emily, too—dear old Emily!"

She laid her hand on her elder sister's arm and looked up affectionately into her face.

"I thought, Irene, I said I wished to speak to you," remarked the Professor then; and before Irene could reply he had taken her hand and led her into the study.

He made her sit down, and seated himself opposite to her.

"Now, my dear," he said, "you are going to be under my roof for a few weeks. The term as a rule lasts about twelve weeks—that is, three months."

"An eternity—impossible to live through it," said Irene.

"I hope you may not find it an eternity; but, anyhow, it is arranged that you are to stay here, and during that time you must be subjected to the rules of discipline."

"What is discipline?" said Irene.

"One of the rules of discipline is to obey those put in command of you."

"In command of me? But there is no one in command of me!"

"I am in command of you, and so is my wife, and so are your three governesses."

"And what do you mean to do now that you are in command of me?"

"I, for one, hope to help you, Irene, to be a good girl."

"I think," said Irene steadily, "that I'd rather be a naughty girl. When I was at The Follies I used to do what dear Rosamund wished; and then sweet little Agnes came, and she loved me, and I loved her and did kind things for her, and I felt ever so much better; but I am not at all better at your horrid school."

"Did any one ever happen to punish you, Irene?"

"Punish me?" said Irene, opening her eyes.

"Yes, punish you."

"Well, no. I don't think anybody would try to do it a second time."

"I don't wish to punish you, my dear child." The Professor rose and took one of Irene's little hands. "I want to help you, dear—to help you with all my might and main. I know you are different from other girls."

"Yes," said Irene, speaking in her old wild strain; "I am a changeling. That's what I am."

"Nevertheless, dear—we won't discuss that—you have a soul within you which can be touched, influenced. All I ask of you is to obey certain rules. One of them is that you do not say unkind things about your fellow-pupils. Now, you spoke very unkindly to my daughter at supper to-night."

"I don't like her," said Irene bluntly.

"But that doesn't alter the fact that she is my daughter and one of your school-fellows."

"Well, I can't like her if I can't. You don't want me to be dishonest and tell lies, do you?"

"No, but I want you to be courteous; and ill-feelings are always wrong, and can be mastered if we apply ourselves in the right spirit. I must, therefore, tell you, Irene, that the next time I hear you speak, or it is reported to me that you speak, unkindly of any of your school-fellows, and if you perform any naughty, cowardly, childish tricks, you will have to come to me, and—I don't quite know what I shall be obliged to do, but I shall have a talk with you, my dear. Now, that is enough for the present."

"Thank you," said Irene, turning very red, and immediately leaving the room.

The Professor sighed when she had gone.

"How are we ever to manage her?" he said to himself.

In truth, he had not the least idea. Irene was not the sort of girl who could be easily softened, even by a nature as gentle and kind and patient as his. She required firm measures. Nevertheless, he had made a deeper impression than he had any idea of; and when the little girl went up to her room presently, and saw that Agnes was in bed, but wide awake and waiting ready to fling her arms tightly round her companion's neck, some of the sore feeling left her heart.

"Oh, Aggie, I have you! and you will never, never love that other horrid Agnes, or that dreadful Phyllis, or that hateful Lucy, or any of the girls in the school as you love me."

"Oh, indeed, I never could, Irene—I never could!" said little Agnes. "But you don't mind Em putting me to bed, do you, for it makes her so happy? Her hands were quite trembling with joy, and she said she had not been so happy for a long time."

"Well, she is your sister, and she's a good old sort. But, Agnes, how are we to live in this school? Tell me, can you endure it?"

"I was at another school, and this one seems perfectly beautiful," said little Agnes. "I think all the girls are quite nice."

"You had better not begin to praise them overmuch, or I shall be jealous."

"What is being jealous?" said the little girl.

"Why, just furious because somebody cares for you, or even pretends to care for you. I don't want anybody to love you but myself."

"I don't think I should quite like that," said little Agnes. "Though I have promised to love you best, I should like others to be kind to me."

"There you are, with your sweet little eyes full of tears, and I have caused them! But I'm dead-tired myself. Anyhow, it will only last for twelve weeks—truly an eternity, but an eternity which has an end. Shall we sleep in one bed to-night, Agnes? I won't be a moment undressing. Will you come and cuddle close to me, and let me put my arms round you and feel that you are my own little darling?"

"Yes, indeed, I should love it!" said little Agnes.

CHAPTER XXIV. GUNPOWDER IN THE ENEMY'S CAMP.Miss Archer was a most splendid director of a school. She was the sort of woman who could read girls' characters at a glance; and as her object was to spare Mrs. Merriman all trouble, and as she was now further helped by Miss Frost, a most excellent teacher herself, and Mademoiselle Omont took the French department, there was very little trouble in arranging the lessons of the different girls.

Irene, on the morning after her arrival, awoke in a bad temper, notwithstanding the fact that sweet little gentle Agnes was lying close to her, with her pretty head of fair hair pressed against the elder girl's shoulder. But when she went downstairs, and took her place in the class, and found that, after all, she was not such an ignoramus as her companions evidently expected to find her, her spirits rose, and for the first time in her existence a sense of ambition awoke within her. It would be something to conquer Lucy Merriman—the proud, the disdainful, the unpleasant Lucy. After what Professor Merriman had said, Irene made up her mind to say nothing more in public against Lucy; but her real feelings of dislike toward her became worse and worse.

Now, Lucy's feelings towards Irene, which were those of contempt and utter indifference until they met, were now active. She was amazed to find within herself a power of disliking certain of her fellow-creatures which she never thought she could have possessed. She was not a girl to make violent friendships, but she did not know that she could dislike so heartily. She hated Rosamund with a goodly hatred, but now that hatred was extended to Irene. Why should Irene be so pretty and yet so naughty, so lovable and yet so detestable? For very soon the peculiar little girl began to exercise a certain power over more than one other girl in the school; and except that she kept herself a good deal apart, and absorbed little Agnes Frost altogether, for the first week she certainly did nothing that any one could complain of. Then she was not only remarkable for her beauty, which must arrest the attention of everybody, but she was also undeniably clever. Laura Everett was greatly taken with her, so was Annie Millar, so was Phyllis Flower, and so was Agnes Sparkes. Rosamund assumed the position of a calm and careful guardian angel over both Irene and little Agnes. She had a talk with both Mrs. Merriman and the Professor, and also with Miss Frost, on the day after their arrival.

"I will promise to be all that you want me to be if you will allow me to have a certain power over Irene and over little Agnes Frost, a power which will be felt rather than seen. I want little Agnes to sit next to Irene at meals; and I want this not for Agnes' sake—for she is such a dear little girl that she would make friends wherever she was placed—but for Irene's sake, for I don't want

Comments (0)