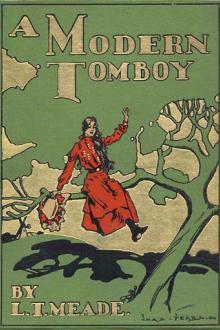

A Modern Tomboy by L. T. Meade (e book reader pc txt) 📕

CHAPTER II.

ROSAMUND TAKES THE LEAD.

Before that day had come to an end, Lucy had discovered how true were Phyllis Flower's words. For Rosamund Cunliffe, without making herself in the least disagreeable, without saying one single rude thing, yet managed to take the lead, and that so effectively that even Lucy herself found that she could not help following in her train.

For instance, after dinner, when the girls--all of them rather tired, and perhaps some of them a little cross, and no one exactly knowing what to do--clustered about the open drawing-room windows, it was Rosamund who proposed that the rugs should be rolled back and that they should have a dance.

Lucy opened her eyes. Nobody before had ever dared to make such a suggestion in the house of Sunnyside. Lucy, it is true, had dancing lessons from a master who came once a week to instruct her and other girls in the winter season, and she had occasionally gone

Read free book «A Modern Tomboy by L. T. Meade (e book reader pc txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: L. T. Meade

- Performer: -

Read book online «A Modern Tomboy by L. T. Meade (e book reader pc txt) 📕». Author - L. T. Meade

"Well, I must say, Irene, speaking honestly, I hate her too. But we must both make up our minds not to mind her. She cannot really hurt us."

"Hurt us?" said Irene. "I'm sure I'm not afraid of her, if that is what you mean."

"Well, that's all right. Now, let us go to bed."

"I believe I am very tired too. I will promise to be quite good while you are away, so you need not have any anxiety on my account, darling," said Irene; and she kissed Rosamund several times.

The night passed, and early the next morning Rosamund, accompanied by Miss Frost, took her departure. There was a certain loneliness felt in the school, for Rosamund was exceedingly popular with every girl in the place, with the sole exception of Lucy Merriman. Busy school-life, however, gives little time for regrets or even for loneliness. Each moment of time is carefully marked out, each hour has its appointed task, and the girls were, to all appearance, as happy as usual. Little Agnes did not in the very least miss Rosamund or her own sister Emily. Her whole soul was set upon Irene, who helped her with her lessons, walked with her, and hardly ever let her out of her sight.

In the course of the evening Lucy was seen to go up to Phyllis Flower.

"Now, Phyllis," she said, "here is your chance. I've got the very thing that will do the business. We must get Agnes to bed, and a little later, when she is asleep, you shall creep into the room and just slip this thing under the bedclothes. She won't know who has done it. She will wake out of her first sleep, and naturally think that it is Irene's doing."

As Lucy spoke she drew Phyllis towards a corner of the playground, where a large, rather ferocious-looking hedgehog was curled up in a ball.

"But that—that would almost kill the child," said Phyllis, starting back.

"We must give her a good fright; it is the only way to effect our purpose. Then one or other of us must be near, and intercept her, and tell her that we will be her friends. Then you will have your week with me in London; but you must do it."

"I almost think," said Phyllis, turning very white, "that I'd rather not have my week. You can do it yourself if you like. It seems so cruel, and they are very happy together, and she is a very timid little thing. And just when her sister is not at home!"

"That is the very time. I am going to have a chat with little Agnes this evening. I am going in a certain way to prepare her—not much. Now, don't be a goose, Phyllis. Think what a jolly time you will have in London. It will be quite impossible for us to be found out."

Lucy talked to Phyllis for some time, and finally persuaded her to act as her accomplice in the matter.

It was a rule at Sunnyside that the smaller girls, consisting of Phyllis Flower, Agnes Sparkes, and little Agnes Frost, should go to bed quite an hour before the other girls. They usually had supper of milk and a few biscuits, and went to their room not later than eight o'clock. The other girls did not go to bed until half-past nine, and had a more substantial meal at eight o'clock. Phyllis Flower, therefore, for every reason, was best able to perform the mean trick by which Lucy meant to sever the friendship between Irene and little Agnes; but the child must be slightly alarmed, otherwise the hedgehog might be put into the bed and she know nothing about it.

Consequently, just before the younger children's simple supper was brought in on a tray, Lucy came and sat down near Agnes Frost.

"You must miss your Emily," she said.

Her tone was quite caressing and gentle. Little Agnes—who did not like Lucy, but could not in her heart of hearts cherish ill-will towards any one—raised her eyes now and said gently, "Of course I miss her; but then, I have my dear Irene."

Lucy put on a smile which meant wonderful things.

"You are a very courageous little girl," she said after a pause.

Little Agnes was silent for a minute; then she said gravely, "I know exactly what you mean by that, and I think you are mistaken. You said things about my Irene which are not true."

"Oh, indeed! you accuse me of falsehood, do you?" said Lucy.

"Well, perhaps not exactly of falsehood; but I don't think it was kind of you to tell me, for Irene is changed now. She could never do cruel things now."

"She will never be changed. Don't you understand that she is not like ordinary people? She is a sort of fairy, hardly like a human being at all. I may as well tell you, now that Rosamund and Miss Frost are away, that while Rosamund slept in the next room you were practically safe. I will admit, although I have no love for Rosamund Cunliffe, that she is a very brave and plucky girl. To-night, however——But I trust it will be all right. I don't want to make you nervous. I trust it will be all right."

Lucy moved off and sat down before her books and pretended to read. By-and-by Irene, looking lovely in one of her prettiest pale-blue dresses, entered the room. Little Agnes was sipping her milk very slowly. Irene ran straight up to her. She had the power of almost divining a person's thoughts, and she was conscious that the child was troubled.

"What is it, pet?" she said. "Has anybody vexed you?"

"Oh, nobody—nobody, indeed, dear Irene."

"Well, that is all right. I wish I could go to bed with you to-night."

"I wish you could," said the child nervously.

"But I can't. I have an awfully stiff piece of work to get through before the morning, and I am determined to be first in my form, otherwise Lucy Merriman will get ahead of me, and that she shall not."

"But I sha'n't be nervous really."

"No, of course not, dear. What is there to be nervous about?"

Irene was really absorbed in an intricate calculation which she had to make with regard to a very advanced sum, and sat down at a distant table, and forgot for the time being even little Agnes. Agnes, therefore, went up to bed alone. There was no Miss Frost to help her to undress, there was no one to take any notice of her, and there were the fearful stories that Lucy kept hinting at ringing in her ears. Yes, Irene had done dreadful things. Yes, she had. But Irene to her was perfect. She had no fear with her; she was happy with her. But then, Lucy Merriman had said that that was because little Agnes was so well protected. She had Rosamund sleeping practically in the same room, and Miss Frost, her own sister, not far away. Irene did not dare to do anything dreadful. But she had done dreadful things. She had nearly killed poor Miss Carter. She had made her own beloved sister swallow insects instead of pills. In short, she was just what Lucy had described her to be. And Lucy had said another dreadful thing to-night. She had hinted that Irene was not exactly to blame, for she was not like an ordinary girl; she was a sort of fairy girl. Now, Agnes had read several fairy-tales, and knew, supposing such a wonderful thing as a fairy really lived in the world, that she might be influenced by some other fairies, who would guide her, and help her, and force her to do things whether she liked them or not. But still she never would be unkind to little Agnes.

"It is a perfect shame of me even to think of it," said the little girl to herself. "I am ever so sleepy, but still I'll just look under the pillow. Oh, suppose Fuzz or Buzz were there, wouldn't I just scream with terror?"

But the pillow was quite innocent and harbored no obnoxious thing; the bed was smooth and white as usual; and little Agnes undressed, not quite as carefully as when Miss Frost was looking after her, and getting into bed, laid her head on the pillow, and presently fell fast asleep.

She had not been asleep more than a quarter of an hour before the room door was opened most carefully (the lock had been oiled in advance by Lucy), and Phyllis Flower, carrying the hedgehog, came in. She drew down the bedclothes and laid the hedgehog so that its prickles would just touch the child in case she moved, and then as carefully withdrew. She hated herself for having done it. All was quiet in that part of the house, which was far away from the schoolrooms, and no one heard a child give a terrible scream a few minutes later; and no one saw that same child spring out of bed, hastily put on her clothes, and rush downstairs in wild distress and despair.

Lucy had meant to be close at hand to comfort little Agnes when fright overtook her. But she had been called away to do some writing for her father. Laura Everett was busy attending to her own work. Phyllis Flower was in bed and asleep. She had earned her trip to London, and was dreaming about the delights of that time. No one heard that scream, which was at once faint and piteous. No one heard the little feet speed through the hall, and no one saw the little figure stealthily leave the house. Little Agnes was going to run away. Yes, there was no doubt whatever now in her mind: her darling Irene was a fairy, a changeling. She had done the most cruel and awful thing.

When little Agnes had seen the hedgehog in her bed she was far too terrified even to recognize the nature of the creature that had been made her bedfellow. But she felt sure that Lucy's words were right: that Irene was a wicked changeling, and that the sooner she got away from her the better. The child was too young to reason, too simple by nature to give any thought to double-dealing. All she wanted now was to get away. She could not stay another minute in the house. Her love for Irene was swallowed up altogether by her wild terror. She trembled; she shook from head to foot.

It was a bitterly cold winter's night, and the child was only half-clothed. She had forgotten to put on anything but her house-shoes, and had not even a hat on her head. But that did not matter. She was out, and there was no terrible Irene to come near her, no wicked fairy to do her damage. She would stay out all night if necessary. She would hide from Irene. She could never be her friend again.

The terror in her little heart rendered her quite unreasonable for the time being. She was, in short, past reason. By-and-by she crept into the old bower where Rosamund and Irene had spent a midsummer night—a night altogether very different from the present one, for the bower was not waterproof, and the cold sleet came in and fell upon the half-dressed child. She sank down on the seat, which was already drenched; but little she cared. She crouched there, wondering what was to be the end, and giving little cries of absolute anguish now and then.

CHAPTER XXVII. "MY OWN IRENE!"Irene went up to bed that night in her usual spirits. She longed for the moment when she could, as usual, kiss little Agnes; but she

Comments (0)