Young Robin Hood by George Manville Fenn (classic children's novels TXT) 📕

Read free book «Young Robin Hood by George Manville Fenn (classic children's novels TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: George Manville Fenn

Read book online «Young Robin Hood by George Manville Fenn (classic children's novels TXT) 📕». Author - George Manville Fenn

"Yes, yes," he said softly, "I can bear it now. Speak, pray speak, and tell me all."

"But you will not be angry with me if I am wrong, Master Sheriff?"

"No, no," said Robin's father; "speak out at once."

"Well, Master Sheriff, no one would tell me when I asked questions, but there's a little fellow there, dressed all in Lincoln green, like one of Robin Hood's fighting men, with his sword and bugle, and bow and arrows, and somehow I began to think, and then I began to ask, whether he was Robin Hood's son; but those I asked only shook their heads.

"That made me think all the more, and one day I managed to follow him but among the trees to where I found him feeding one of the wild deer, which followed him about like a dog."

"I waited a bit, and then stepped out to him, and what do you think he did? He strung his bow, fitted an arrow to it before I knew where I was, and drew it to the head as if he was going to shoot me. 'Do you know where Nottingham is?' I said, and he lowered his bow. 'Yes,' he said, 'of course. Do you know my father?' 'Do I know the Sheriff?' I said; 'of course.' 'Are you going there soon?' he cried, and I nodded. 'Then you go to my father,' he cried, 'and tell him to tell aunt that I'm quite well, and that some day I'm coming home."

The man stopped, for just then the Sheriff closed his eyes again and said something very softly, which Robin's aunt heard, and she sank upon her knees and covered her face with her hands.

Then the Sheriff sprang to his feet, looking quite a different man.

"Here," he said to the bringer of the news, and he gave him some gold pieces. "Could you find your way back to the outlaws' camp in the forest?"

"Oh! yes, Master Sheriff, that I could, though they did bind a cloth over my face when they brought me away."

"And you could lead me and a strong body of fighting men right to the outlaws' camp?"

"I could, Master Sheriff," said the man, beginning slowly to lay the gold pieces back one by one upon the table; "but I can't do evil for good."

"What?" cried the Sheriff angrily. "They are robbers and outlaws, and every subject of the King has a right to slay them."

"May be, Master Sheriff," said the man drily; "but I'm not going to fly at the throat of one who did nothing but good to me. They tell me that Robin Hood's a noble earl who offended the King, and had to fly for his life. What I say is, he's a noble kind-hearted gentleman, and if it was my boy he had there, looking as happy as the day is long, I'd go to him without any fighting men."

"How, then?" cried the Sheriff.

"Just like a father should, master, and ask him for my boy like a man."

"That will do," said the Sheriff. "You can go."

The man turned to leave the room, when the Sheriff said sharply:

"Stop! You are leaving the gold pieces I gave you."

"Yes, I can't take pay to lead anyone to fight against Robin Hood and his men."

"Those pieces were for the news you brought me," said the Sheriff.

"Yes, take them, for you have behaved like an honest man."

But the Sheriff did not take the man's advice, neither did he listen to the appeal of young Robin's aunt. For, as Sheriff of Nottingham, he said to himself that it was his duty to destroy or scatter the band of outlaws who had lived in Sherwood Forest for so long a time.

So he gathered a strong body of crossbow-men, and others with spears and swords, besides asking for the help of two gallant knights who came with their esquires mounted and in armour with their men.

Somehow Robin Hood knew what was being prepared, and about a week after, when the Sheriff and his great following of about three hundred men were struggling to make their way through the forest, they heard the sound of a horn, and all at once the thick woodland seemed to be alive with archers, who used their bows in such a way that first one, then a dozen, then by fifties, the Sheriff's men began to flee, and in less than an hour they were all crawling back to Nottingham, badly beaten, not a man among them being ready to turn and fight.

In another month the Sheriff advanced again with a stronger force, but they were driven back more easily than the first, and the Sheriff was in despair.

But a couple of days later he had the man to whom he had given the gold pieces found, and sent him to the outlaws' camp with a letter written upon parchment, in which he ordered Robin Hood, in the King's name, to give up the little prisoner he held there contrary to the law and against his own will.

It was many weary anxious days before the messenger came back, but without the little prisoner.

"What did he say?" asked the Sheriff.

"He said, master, that if you wanted the boy you must go and fetch him."

It was the very next day that the Sheriff went into the room where young Robin's aunt was seated, looking very unhappy, and she jumped up from her chair wonderingly on seeing that her brother-in-law was dressed as if for a journey, wearing no sword or dagger, only carrying a long stout walking staff.

"Where are you going, dear?" she said.

"Where I ought to have gone at first," he said humbly; "into the forest to fetch my boy."

"But you could never find your way," she said, sobbing. "Besides, you are the Sheriff, and these men will seize and kill you."

"I have someone to show me the way," said the Sheriff gently; "and somehow, though I have persecuted and fought against the people sorely, I feel no fear, for Robin Hood is not the man to slay a broken-hearted father who comes in search of his long-lost boy."

CHAPTER VIIIThe sun was low down in the west, and shining through and under the great oak and beech trees, so that everything seemed to be turned to orange and gold.

It was the outlaws' supper time, the sun being their clock in the forest; and the men were gathering together to enjoy their second great meal of the day, the other being breakfast, after having which they always separated to go hunting through the woods to bring in the provisions for the next day.

Robin Hood's men, then, were scattered about under the shade of a huge spreading oak tree, waiting for the roast venison, which sent a very pleasant odor from the glowing fire of oak wood, and young Robin was seated on the mossy grass close by the thatched shed which formed the captain's headquarters, where Maid Marian was busy spreading the supper for the little party who ate with Robin Hood himself.

Little John was there, lying down, smiling and contented after a hard day's hunting, listening to young Robin, who was displaying the treasures he had brought in that day, and telling his great companion where he had found them.

There were flowers for Maid Marian, because she was fond of the purple and yellow loosestrife, and long thick reeds in a bundle.

"You can make me some arrows of those," said Robin; "and I've found a young yew tree with a bough quite straight. You must cut that down and dry it to make me a bigger bow. This one is not strong enough."

"Very well, big one," said Little John, smiling and stretching out his hand to smooth the boy's curly brown hair. "Anything else for me to do?"

"Oh yes, lots of things, only I can't think of them yet. Look here, I found these."

The boy took some round prickly husks out of his pocket.

"Chestnuts—eating ones."

"Yes, I know where you got them," said Little-John, "but they're no good. Look."

He tore one of the husks open, and laid bare the rich brown nut; but it was, as he said, good for nothing, there being no hard sweet kernel within, nothing but soft pithy woolly stuff.

"No good at all," continued the great forester; "but I'll show you a tree which bears good ones, only the nuts are better if they're left till they drop out of their husks."

"And then the pigs get them," said Robin.

"Then you must get up before the pigs, and be first. Halloa! What now?"

For a horn was blown at a distance, and the men under the great oak tree sprang to their feet, while Robin Hood came out to see what the signal meant.

Young Robin, who was now quite accustomed to the foresters' ways, caught up his bow like the rest, and stood looking eagerly in the direction from which the cheery sounding notes of the horn were blown.

He had not long to wait, for half a dozen of the merry men in green came marching towards them with a couple of prisoners, each having his hands fastened behind him with a bow-string and a broad bandage tied over his eyes, so that they should not know their way again to the outlaws' stronghold.

"Prisoners!" said young Robin.

"Poor men, too," grumbled Little John.

"Then you'll give them their supper and send them away to-morrow morning," said young Robin.

"I suppose so," said Little John, "but I don't know what made our fellows bring them in."

"Let's go and see," said young Robin.

Little John followed as the boy marched off, bow in hand, to where Robin Hood was standing, waiting to hear what his men had to say about the prisoners they had brought in. And as they drew near the boy saw that one was, a homely poor-looking man with round shoulders, the other, well dressed in sad-colored clothes, and thin and bent. But the boy could see little more for the broad bandage, which nearly covered the prisoner's face and was tied tightly behind over his long, gray hair, while his gray beard hung down low.

Young Robin looked pityingly at this prisoner, and a longing came over him to loosen the thong which tied his hands tightly behind him, and take off the bandage so that he could breathe freely, but just then Robin Hood cried:

"Well, my lads, whom have we here?"

The bowed down gray-haired prisoner rose erect at this, and cried:

"Is that Robin Hood who speaks?"

Before the outlaw could answer; he was stopped by a cry: from the boy, who threw down his bow and darted to the prisoner's side.

"Father!" he cried; and he leaped up, as active now as one of the deer of the forest, to fling his arms about the prisoner's neck.

But only for a moment.

The next he had dropped to the ground, to look fiercely round at the astonished men, as he drew the dagger which hung from his belt.

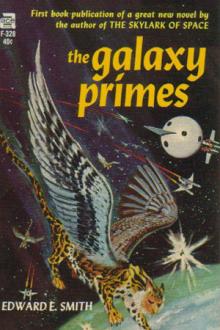

[Illustration: Robin looked fiercely round at the astonished men, as he drew the dagger which hung from his belt.]

"Who dared do this?" he cried, as he reached up to tear the bandage from the face bending over him, and then darted round to begin sawing at the thong which held his father's hands.

Little John took a step or two forward to help the boy, but Robin Hood held up his hand to keep him back, and a dead silence fell upon the great group of foresters who had pressed forward, and who eagerly watched the scene before them in the soft, amber sunshine which came slanting through the trees. The task was hard, but the little fellow worked well, and many moments had not elapsed before the prisoner's hands were free, and as if seeing no one but the little forester before him in green, and quite regardless of all around, he dropped upon his knees, clasped the boy to his breast, and softly whispered the words:

"Thank God!"

Young Robin's arms were tightly round his father's neck by this time, and he was kissing the

Comments (0)