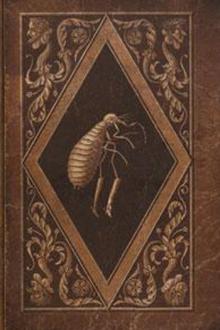

Master Flea by E. T. A. Hoffmann (i read a book txt) 📕

The elder Mr. Tyss had always considered it a bad omen that Peregrine, as a little child, should prefer counters to d

Read free book «Master Flea by E. T. A. Hoffmann (i read a book txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: E. T. A. Hoffmann

- Performer: -

Read book online «Master Flea by E. T. A. Hoffmann (i read a book txt) 📕». Author - E. T. A. Hoffmann

Leuwenhock had perceived, as well as Swammerdamm, the paramount influence which Peregrine had over both of them; and the first use, which they made of their renewed friendship, was, to consider in unison the strange horoscope of Mr. Tyss, and, as far as possible, to interpret it.

"What my friend, Leuwenhock, could not do alone," continued the microscopist, "was effected by our united powers, and thus this was the second experiment which, in spite of all the obstacles opposed to us, we undertook with the most splendid results."

"The short-sighted fool!" lisped Master Flea, who sate upon the pillow, close to Peregrine's ear. "He still fancies that the Princess, Gamaheh, was restored to life by him. A pretty life, indeed, is that, to which the awkwardness of the two microscopists has condemned the poor thing!"

"My dear friend," continued Swammerdamm, who had the less heard Master Flea, as he had just then begun to sneeze loudly, "my dear friend, you are particularly chosen by the spirit of the creation, a pet-child of nature, for you possess the most wonderful talisman, or, to speak more correctly and scientifically, the most splendid Tsilmenaja, or Tilsemoht, that was ever fed by the dew of heaven, and has sprung from the lap of earth. It is an honour to my art that I, and not Leuwenhock, have discovered that this lucky talisman sleeps for a time till a certain constellation enters, which finds its centre-point in your worthy person. With yourself, my dear friend, something must, and will, happen, which in the moment the power of the talisman awakes, may make that waking known to you. Let Leuwenhock have told you what he will, it must all be false; for, in regard to that point, he knew nothing at all, until I opened his eyes. Perhaps he tried to frighten you, my dear friend, with some terrible catastrophe, for I know he likes to terrify people without reason.--But trust to me, Mr. Tyss, who have the highest respect for you, and swear it to you most solemnly, you have nothing to fear. I should like, however, to learn, whether you do not as yet feel the presence of the talisman, and what you think of the matter altogether."

At these last words Swammerdamm eyed his host as keenly as if he would pierce his deepest thoughts; but of course he did not succeed so well in that as Peregrine with his microscopic glass, by means of which the latter learnt that it was not so much the united war with the Amateur and the Barber, as the mysterious horoscope, that had brought about the reconciliation of the microscopists. It was the possession of the mighty talisman that both were striving after. In regard to the mysterious lines in the horoscope of Peregrine, Swammerdamm remained in as vexatious ignorance as Leuwenhock; but he fancied the clue must lie within Peregrine, which would lead to the discovery of the mystery. This clue he now sought to fish out of the novice, and then rob him of the inestimable treasure before he knew its value. He was convinced this talisman was equal to that of the wise Solomon, since, like that, it gave him who possessed it the perfect dominion over the kingdom of spirits.

Peregrine paid like with like, himself mystifying Swammerdamm, who thought to mystify him. He contrived to answer so dexterously, in such figurative speeches, that the microscopist feared the initiation had already begun, and that soon the mystery would be revealed which neither he nor Leuwenhock had been able to unravel.

Swammerdamm cast down his eyes, hemmed, and stammered a few unintelligible words; he was really in a bad plight, and his thoughts were all in confusion.

"The devil! What's this? Is this Peregrine, who speaks to me? Am I the learned Swammerdamm or an ass?"

In despair he at last collected himself, and began,

"But to come to something else, most respected Mr. Tyss, and, as it seems to me, something much more agreeable."--

According to what Swammer now went on to say, both he and Leuwenhock had perceived, with great pleasure, the strong inclination which Dörtje Elverdink had conceived for him. If they had both formerly been of a different opinion, each believing that Dörtje should stay with himself, and not think of love and marriage, yet they had now both come to a better conviction. They fancied that they read in Peregrine's horoscope, he positively must take Dörtje Elverdink for his wife, as the greatest advantage in all the conjunctures of his life, and, as neither doubted for a moment that he was equally enamoured of her, they had looked upon the matter as fully settled. Swammerdamm, moreover, was of opinion that Peregrine was the only one who, without any trouble, could beat his rivals out of the field; and that the most dangerous opponents, namely, the Amateur and the Barber, could avail nothing against him.

Peregrine found, from Swammerdamm's thoughts, that both the microscopists actually imagined they had read in his horoscope the inevitable necessity of his marriage with Dörtje. It was to this supposed necessity only they yielded, thinking to draw the greatest gain from the apparent loss of the little-one, namely, by getting possession of Mr. Tyss and his talisman. But it may be easily supposed how little faith he must have in the science of the two microscopists, when neither of them was able to solve the centre-point of the horoscope. He did not, therefore, at all yield to that pretended conjunction, which conditioned the necessity of his marriage with Gamaheh, and found no difficulty whatever in declaring positively, that he renounced her hand in favour of his best friend, George Pepusch, who had older and better claims to the fair one, and that he would not break his word upon any condition.

Swammerdamm raised his green eyes, which he had so long cast down, stared vehemently at Peregrine, and grinned with the cunning of a fox, as he said, if the friendship between him and Pepusch were the only scruple which kept him from giving free scope to his feelings, this obstacle existed no longer: Pepusch had perceived, although slightly touched with madness, his marriage with Dörtje was against the stars, and nothing could come from it but misery and destruction. He had therefore resigned all his pretensions, declaring only that, with his life, he would protect Gamaheh,--who could belong to no one but his bosom-friend, Tyss,--against the awkward dolt of an Amateur and the bloodthirsty Barber.

A cold shudder ran through Peregrine, when he perceived, from Swammerdamm's thoughts, that all was true which he had spoken. Overpowered by the strangest and the most opposite feelings, he sank back upon his pillow and closed his eyes. The microscopist pressed him to come down himself, and hear from Dörtje's mouth, from George's, the present state of things, and then took his leave with as much ceremony as he had entered.

Master Flea, who sate the whole time quietly on the pillow, suddenly leaped up to the top of Peregrine's nightcap. There he raised himself up on his long hind-legs, wrung his hands, stretched them imploringly to Heaven, and cried out in a voice half stifled with tears,

"Woe to poor me! I already thought myself safe, and now comes the most dangerous trial. What avail me the courage, the constancy of my noble patron?--I surrender myself! All is over."

"Why," said Mr. Tyss, in a faint voice--"why do you lament so on my nightcap, my dear master? Do you fancy that you alone have to complain? that I myself am not in the unhappiest situation in the world? for my whole mind seems broken up, and I neither know what to do, nor which way to turn my thoughts. But do not fancy, my dear master, I am foolish enough to venture near the rock upon which all my resolutions might be shipwrecked. I shall take care not to follow Swammerdamm's invitation, and to avoid seeing the alluring Dörtje Elverdink."

"In reality," said Master Flea, after he had taken his old post, upon the pillow, by Peregrine's ear,--"in reality I am not sure that I ought not to advise you to go at once to Swammerdamm's, however destructive it may appear to myself. It seems to me as if all the lines of your horoscope were running quicker and quicker together, and you yourself were upon the point of entering the red centre.--Well, let the dark destiny have decreed what it will, I plainly perceive even a Master Flea cannot escape such a conclusion, and it is as simple as useless to expect my safety from you. Go then, take her hand, deliver me to slavery, and, that all may happen as the stars will it, without any interference, make no use of the microscopic glass."

"Formerly," said Peregrine,--"formerly, Master Flea, your heart seemed stout, your mind firm, and now you have grown so fainthearted!--You may be as wise as you will, but you have no good idea of human resolution, and, at all events, rate it too meanly.--Once more--I will not break my word to you, and that you may perceive how fixed my determination is, of not seeing the little-one again, I will now rise and betake myself, as I did yesterday, to the bookbinder's."

"Oh Peregrine!" cried Master Flea, "the will of man is a frail thing; a passing air will break it. How immense is the abyss lying between what man wills and what really happens! Many a life is only a constant willing, and many a one, from pure volition, at last does not know what he will. You will not see Dörtje Elverdink, and yet who will answer for it that you do not see her in the very moment of your declaring such a resolution?"

Strange enough, the very thing really happened which Master Flea had prophesied.

Peregrine arose, dressed himself, and, faithful to his intention, would have gone to the bookbinder. In passing Swammerdamm's chamber, the door was wide open, and,--he knew not how it happened,--he stood, leaning on Swammerdamm's arm, close before Dörtje Elverdink, who sent him a hundred kisses, and with her silver voice cried out, joyfully, "Good morning, my dear Peregrine!"--George Pepusch, too, was there, looking out of the window and whistling. He now flung the window to with violence, and turned round.

"Ha!" he exclaimed as if he had just then seen Peregrine--"ha! look! You come to see your bride. That's all in order, and any third person would only be in the way. I too will take myself off; but let me first tell you, my good friend, Peregrine, that George Pepusch scorns every gift which a compassionate friend would fling to him as if he were a beggar. Cursed be every sacrifice! I will have nothing to thank you for. Take the beautiful Gamaheh, who so warmly loves you; but take care the Thistle, Zeherit, do not take root, and burst the walls of your house."

George's

Comments (0)