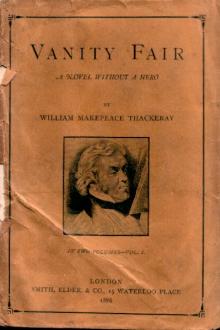

The Virginians by William Makepeace Thackeray (top books to read txt) 📕

Read free book «The Virginians by William Makepeace Thackeray (top books to read txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William Makepeace Thackeray

Read book online «The Virginians by William Makepeace Thackeray (top books to read txt) 📕». Author - William Makepeace Thackeray

Now, when I ask a question of my dear oracle, I know what the answer will be; and hence, no doubt, the reason why I so often consult her. I have but to wear a particular expression of face and my Diana takes her reflection from it. Suppose I say, “My dear, don't you think the moon was made of cream cheese to-night?” She will say, “Well, papa, it did look very like cream cheese, indeed—there's nobody like you for droll similes.” Or, suppose I say, “My love, Mr. Pitt's speech was very fine, but I don't think he is equal to what I remember his father.” “Nobody was equal to my Lord Chatham,” says my wife. And then one of the girls cries, “Why, I have often heard our papa say Lord Chatham was a charlatan!” On which mamma says, “How like she is to her Aunt Hetty!”

As for Miles, Tros Tyriusve is all one to him. He only reads the sporting announcements in the Norwich paper. So long as there is good scent, he does not care about the state of the country. I believe the rascal has never read my poems, much more my tragedies (for I mentioned Pocahontas to him the other day, and the dunce thought she was a river in Virginia); and with respect to my Latin verses, how can he understand them when I know he can't construe Corderius? Why, this notebook lies publicly on the little table at my corner of the fireside, and any one may read in it who will take the trouble of lifting my spectacles off the cover: but Miles never hath. I insert in the loose pages caricatures of Miles: jokes against him: but he never knows nor heeds them. Only once, in place of a neat drawing of mine, in China-ink, representing Miles asleep after dinner, and which my friend Bunbury would not disown, I found a rude picture of myself going over my mare Sultana's head, and entitled “The Squire on Horseback, or Fish out of Water.” And the fellow to roar with laughter, and all the girls to titter, when I came upon the page! My wife said she never was in such a fright as when I went to my book: but I can bear a joke against myself, and have heard many, though (strange to say, for one who has lived among some of the chief wits of the age) I never heard a good one in my life. Never mind, Miles, though thou art not a wit, I love thee none the worse (there never was any love lost between two wits in a family); though thou hast no great beauty, thy mother thinks thee as handsome as Apollo, or his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, who was born in the very same year with thee. Indeed, she always think Coates's picture of the Prince is very like her eldest boy, and has the print in her dressing-room to this very day.

[Note, in a female hand: “My son is not a spendthrift, nor a breaker of women's hearts, as some gentlemen are; but that he was exceeding like H.R.H. when they were both babies, is most certain, the Duchess of Aneaster having herself remarked him in St. James's Park, where Gumbo and my poor Molly used often to take him for an airing. Th. W.”]

In that same year, with what different prospects! my Lord Esmond, Lord Castlewood's son, likewise appeared to adorn the world. My Lord C. and his humble servant had already come to a coolness at that time, and, heaven knows! my honest Miles's godmother, at his entrance into life, brought no gold pap-boats to his christening! Matters have mended since, laus Deo—laus Deo, indeed! for I suspect neither Miles nor his father would ever have been able to do much for themselves, and by their own wits.

Castlewood House has quite a different face now from that venerable one which it wore in the days of my youth, when it was covered with the wrinkles of time, the scars of old wars, the cracks and blemishes which years had marked on its hoary features. I love best to remember it in its old shape, as I saw it when young Mr. George Warrington went down at the owner's invitation, to be present at his lordship's marriage with Miss Lydia Van den Bosch—“an American lady of noble family of Holland,” as the county paper announced her ladyship to be. Then the towers stood as Warrington's grandfather the Colonel (the Marquis, as Madam Esmond would like to call her father) had seen them. The woods (thinned not a little to be sure) stood, nay, some of the self-same rooks may have cawed over them, which the Colonel had seen threescore years back. His picture hung in the hall which might have been his, had he not preferred love and gratitude to wealth and worldly honour; and Mr. George Esmond Warrington (that is, Egomet Ipse who write this page down), as he walked the old place, pacing the long corridors, the smooth dew-spangled terraces and cool darkling avenues, felt a while as if he was one of Mr. Walpole's cavaliers with ruff, rapier, buff-coat, and gorget, and as if an Old Pretender, or a Jesuit emissary in disguise, might appear from behind any tall tree-trunk round about the mansion, or antique carved cupboard within it. I had the strangest, saddest, pleasantest, old-world fancies as I walked the place; I imagined tragedies, intrigues, serenades, escaladoes, Oliver's Roundheads battering the towers, or bluff Hal's Beefeaters pricking over the plain before the castle. I was then courting a certain young lady (madam, your ladyship's eyes had no need of spectacles then, and on the brow above them there was never a wrinkle or a silver hair), and I remember I wrote a ream of romantic description, under my Lord Castlewood's franks, to the lady who never tired of reading my letters then. She says I only send her three lines now, when I am away in London or elsewhere. 'Tis that I may not fatigue your old eyes, my dear!

Mr. Warrington thought himself authorised to order a genteel new suit of clothes for my lord's marriage, and with Mons. Gumbo in attendance, made his appearance at Castlewood a few days before the ceremony. I may mention that it had been found expedient to send my faithful Sady home on board a Virginia ship. A great inflammation attacking the throat and lungs, and proving fatal in very many cases, in that year of Wolfe's expedition, had seized and well-nigh killed my poor lad, for whom his native air was pronounced to be the best cure. We parted with an abundance of tears, and Gumbo shed as many when his master went to Quebec: but he had attractions in this country and none for the military life, so he remained attached to my service. We found Castlewood House full of friends, relations, and visitors. Lady Fanny was there upon compulsion, a sulky bridesmaid. Some of the virgins of the neighbourhood also attended the young Countess. A bishop's widow herself, the Baroness Beatrix brought a holy brother-in-law of the bench from London to tie the holy knot of matrimony between Eugene Earl of Castlewood and Lydia Van den Bosch, spinster; and for some time before and after the nuptials the old house in Hampshire wore an appearance of gaiety to which it had long been unaccustomed. The country families came gladly to pay their compliments to the newly married couple. The lady's wealth was the subject of everybody's talk, and no doubt did not decrease in the telling. Those naughty stories which were rife in town, and spread by her disappointed suitors there, took some little time to travel into Hampshire; and when they reached the country found it disposed to treat Lord Castlewood's wife with civility, and not inclined to be too curious about her behaviour in town. Suppose she had jilted this man, and laughed at the other? It was her money they were anxious about, and she was no more mercenary than they.

Comments (0)