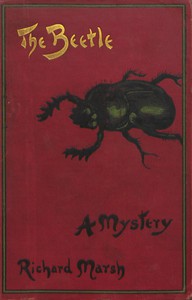

The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (large screen ebook reader TXT) 📕

Read free book «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (large screen ebook reader TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Richard Marsh

Read book online «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (large screen ebook reader TXT) 📕». Author - Richard Marsh

‘This is ’Ammersmith Workhouse, it’s a large place, sir,—which part of it might you be wanting?’

Sydney appealed to Mr Holt. He put his head out of the window in his turn,—he did not seem to recognise our surroundings at all.

‘We have come a different way,—this is not the way I went; I went through Hammersmith,—and to the casual ward; I don’t see that here.’

Sydney spoke to the cabman.

‘Driver, where’s the casual ward?’

‘That’s the other end, sir.’

‘Then take us there.’

He took us there. Then Sydney appealed again to Mr Holt.

‘Shall I dismiss the cabman,—or don’t you feel equal to walking?’

‘Thank you, I feel quite equal to walking,—I think the exercise will do me good.’

So the cabman was dismissed,—a step which we—and I, in particular—had subsequent cause to regret. Mr Holt took his bearings. He pointed to a door which was just in front of us.

‘That’s the entrance to the casual ward, and that, over it, is the window through which the other man threw a stone. I went to the right,—back the way I had come.’ We went to the right. ‘I reached this corner.’ We had reached a corner. Mr Holt looked about him, endeavouring to recall the way he had gone. A good many roads appeared to converge at that point, so that he might have wandered in either of several directions.

Presently he arrived at something like a decision.

‘I think this is the way I went,—I am nearly sure it is.’

He led the way, with something of an air of dubitation, and we followed. The road he had chosen seemed to lead to nothing and nowhere. We had not gone many yards from the workhouse gates before we were confronted by something like chaos. In front and on either side of us were large spaces of waste land. At some more or less remote period attempts appeared to have been made at brickmaking,—there were untidy stacks of bilious-looking bricks in evidence. Here and there enormous weather-stained boards announced that ‘This Desirable Land was to be Let for Building Purposes.’ The road itself was unfinished. There was no pavement, and we had the bare uneven ground for sidewalk. It seemed, so far as I could judge, to lose itself in space, and to be swallowed up by the wilderness of ‘Desirable Land’ which lay beyond. In the near distance there were houses enough, and to spare—of a kind. But they were in other roads. In the one in which we actually were, on the right, at the end, there was a row of unfurnished carcases, but only two buildings which were in anything like a fit state for occupation. One stood on either side, not facing each other,—there was a distance between them of perhaps fifty yards. The sight of them had a more exciting effect on Mr Holt than it had on me. He moved rapidly forward,—coming to a standstill in front of the one upon our left, which was the nearer of the pair.

‘This is the house!’ he exclaimed.

He seemed almost exhilarated,—I confess that I was depressed. A more dismal-looking habitation one could hardly imagine. It was one of those dreadful jerry-built houses which, while they are still new, look old. It had quite possibly only been built a year or two, and yet, owing to neglect, or to poverty of construction, or to a combination of the two, it was already threatening to tumble down. It was a small place, a couple of storeys high, and would have been dear—I should think!—at thirty pounds a year. The windows had surely never been washed since the house was built,—those on the upper floor seemed all either cracked or broken. The only sign of occupancy consisted in the fact that a blind was down behind the window of the room on the ground floor. Curtains there were none. A low wall ran in front, which had apparently at one time been surmounted by something in the shape of an iron railing,—a rusty piece of metal still remained on one end; but, since there was only about a foot between it and the building, which was practically built upon the road,—whether the wall was intended to ensure privacy, or was merely for ornament, was not clear.

‘This is the house!’ repeated Mr Holt, showing more signs of life than I had hitherto seen in him.

Sydney looked it up and down,—it apparently appealed to his aesthetic sense as little as it did to mine.

‘Are you sure?’

‘I am certain.’

‘It seems empty.’

‘It seemed empty to me that night,—that is why I got into it in search of shelter.’

‘Which is the window which served you as a door?’

‘This one.’ Mr Holt pointed to the window on the ground floor,—the one which was screened by a blind. ‘There was no sign of a blind when I first saw it, and the sash was up,—it was that which caught my eye.’

Once more Sydney surveyed the place, in comprehensive fashion, from roof to basement,—then he scrutinisingly regarded Mr Holt.

‘You are quite sure this is the house? It might be awkward if you proved mistaken. I am going to knock at the door, and if it turns out that that mysterious acquaintance of yours does not, and never has lived here, we might find an explanation difficult.’

‘I am sure it is the house,—certain! I know it,—I feel it here,—and here.’

Mr Holt touched his breast, and his forehead. His manner was distinctly odd. He was trembling, and a fevered expression had come into his eyes. Sydney glanced at him, for a moment, in silence. Then he bestowed his attention upon me.

‘May I ask if I may rely upon your preserving your presence of mind?’

The mere question ruffled my plumes.

‘What do you mean?’

‘What I say. I am going to knock at that door, and I am going to get through it, somehow. It is quite within the range of possibility that, when I am through, there will be some strange happenings,—as you have heard from Mr Holt. The house is commonplace enough without; you may not find it so commonplace within. You may find yourself in a position in which it will be in the highest degree essential that you should keep your wits about you.’

‘I am not likely to let them stray.’

‘Then that’s all right.—Do I understand that you propose to come in with me?’

‘Of course I do,—what do you suppose I’ve come for? What nonsense you are talking.

‘I hope that you will still continue to consider it nonsense by the time this little adventure’s done.’

That I resented his impertinence goes without saying—to be talked to in such a strain by Sydney Atherton, whom I had kept in subjection ever since he was in knickerbockers, was a little trying,—but I am forced to admit that I was more impressed by his manner, or his words, or by Mr Holt’s manner, or something, than I should have cared to own. I had not the least notion what was going to happen, or what horrors that woebegone-looking dwelling contained. But Mr Holt’s story had been of the most astonishing sort, my experiences of the previous night were still fresh, and, altogether, now that I was in such close neighbourhood with the Unknown—with a capital U!—although it was broad daylight, it loomed before me in a shape for which,—candidly!—I was not prepared.

A more disreputable-looking front door I have not seen,—it was in perfect harmony with the remainder of the establishment. The paint was off; the woodwork was scratched and dented; the knocker was red with rust. When Sydney took it in his hand I was conscious of quite a little thrill. As he brought it down with a sharp rat-tat, I half expected to see the door fly open, and disclose some gruesome object glaring out at us. Nothing of the kind took place; the door did not budge,—nothing happened. Sydney waited a second or two, then knocked again; another second or two, then another knock. There was still no sign of any notice being taken of our presence. Sydney turned to Mr Holt.

‘Seems as if the place was empty.’

Mr Holt was in the most singular condition of agitation,—it made me uncomfortable to look at him.

‘You do not know,—you cannot tell; there may be someone there who hears and pays no heed.’

‘I’ll give them another chance.’

Sydney brought down the knocker with thundering reverberations. The din must have been audible half a mile away. But from within the house there was still no sign that any heard. Sydney came down the step.

‘I’ll try another way,—I may have better fortune at the back.’

He led the way round to the rear, Mr Holt and I following in single file. There the place seemed in worse case even than in the front. There were two empty rooms on the ground floor at the back,—there was no mistake about their being empty, without the slightest difficulty we could see right into them. One was apparently intended for a kitchen and wash-house combined, the other for a sitting-room. There was not a stick of furniture in either, nor the slightest sign of human habitation. Sydney commented on the fact.

‘Not only is it plain that no one lives in these charming apartments, but it looks to me uncommonly as if no one ever had lived in them.’

To my thinking Mr Holt’s agitation was increasing every moment. For some reason of his own, Sydney took no notice of it whatever,—possibly because he judged that to do so would only tend to make it worse. An odd change had even taken place in Mr Holt’s voice,—he spoke in a sort of tremulous falsetto.

‘It was only the front room which I saw.’

‘Very good; then, before very long, you shall see that front room again.’

Sydney rapped with his knuckles on the glass panels of the back door. He tried the handle; when it refused to yield he gave it a vigorous shaking. He saluted the dirty windows,—so far as succeeding in attracting attention was concerned, entirely in vain. Then he turned again to Mr Holt,—half mockingly.

‘I call you to witness that I have used every lawful means to gain the favourable notice of your mysterious friend. I must therefore beg to stand excused if I try something slightly unlawful for a change. It is true that you found the window already open; but, in my case, it soon will be.’

He took a knife out of his pocket, and, with the open blade, forced back the catch,—as I am told that burglars do. Then he lifted the sash.

‘Behold!’ he exclaimed. ‘What did I tell you?—Now, my dear Marjorie, if I get in first and Mr Holt gets in after me, we shall be in a position to open the door for you.’

I immediately saw through his design.

‘No, Mr Atherton; you will get in first, and I will get in after you, through the window,—before Mr Holt. I don’t intend to wait for you to open the door.’

Sydney raised his hands and opened his eyes, as if grieved at my want of confidence. But I did not mean to be left in the lurch, to wait their pleasure, while on pretence of opening the door, they searched the house. So Sydney climbed in first, and I second,—it was not a difficult operation, since the window-sill was under three feet from the ground—and Mr Holt last. Directly we were in, Sydney put his hand up to his mouth, and shouted.

‘Is there anybody in this house? If so, will he kindly step this way, as there is someone wishes to see him.’

His words went echoing through the empty rooms in a way which was almost uncanny. I suddenly realised that if, after all, there did happen to be somebody in the house, and he was at all disagreeable, our presence on his premises might prove rather difficult to explain. However, no one answered. While I was waiting for Sydney to make the next move, he diverted my attention to Mr Holt.

‘Hollo, Holt, what’s the matter with you? Man, don’t play the fool like that!’

Something was the matter with Mr Holt. He was trembling all over as if attacked by a shaking palsy. Every muscle in his body seemed twitching at once. A strained look had come on his face, which was not nice to see. He spoke as with an effort.

‘I’m all right.—It’s nothing.’

‘Oh, is it nothing? Then perhaps you’ll drop it. Where’s that brandy?’ I handed Sydney the flask. ‘Here, swallow this.’

Mr Holt swallowed the cupful of neat spirit which Sydney offered without an attempt at parley. Beyond bringing some remnants of colour to his ashen cheeks it seemed to have no effect on him whatever. Sydney eyed him with a meaning in his glance which I was at a loss to understand.

‘Listen to me, my lad. Don’t think

Comments (0)