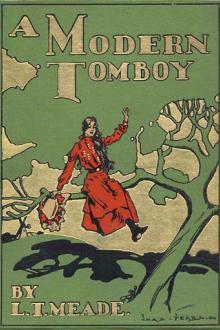

A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls by L. T. Meade (sight word readers .txt) 📕

Read free book «A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls by L. T. Meade (sight word readers .txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: L. T. Meade

Read book online «A Modern Tomboy: A Story for Girls by L. T. Meade (sight word readers .txt) 📕». Author - L. T. Meade

"I?" said Lucy, starting and turning very pale. "Nothing. What should I have done?"

"You know you have done something. You have frightened her, telling her dreadful stories about Irene. You know it. You are mean and cowardly. You ought not to have anything to do with any respectable school. I cannot tell you how I despise you. Think how much I have given up to save Irene, who never had a chance until she knew me, and yet you now destroy every effort that I have made for her good. Oh, I despise you! I cannot help it."

Lucy was absolutely speechless. Rosamund walked along the corridor until she came to Miss Frost's room. She tapped very gently with her knuckles. Miss Frost came out.

"Frosty dear, is little Agnes sleeping with you to-night?" she said.

Miss Frost shut the door and came on to the landing. She put her finger to her lips.

"Hush!" she said. "She is with me; she is in my bed. She is very nervous, starting every moment. Lucy Merriman told her dreadful stories while she was out to-day. The child told me about them. Lucy had no right to tell her. She is afraid of Irene now."

"She need never be afraid of Irene. I wonder if she has pluck enough to go back to her? If she has, all will be safe. If not, Irene's character will be spoiled for ever. Is she asleep?"

"Scarcely asleep; very nervous and restless. You won't take her back to Irene to-night? You know what the effect of nervous fear is upon a delicate, tenderly nurtured child. You could not be so cruel."

"Agnes is not so delicate as all that. She can stand it. When I think of Irene, who has almost been saved, who has almost been turned into the paths of goodness and righteousness, and mostly by little Agnes herself, and when I think of that cruel, wicked, unscrupulous girl, I have no patience. Frosty, I have helped you—you must let little Agnes help Irene now. Don't be frightened. I shall be next door to them, and nothing can possibly happen to the child; but she must come back."

Miss Frost stood aside.

"Really, Rosamund," she said, "I do admit the strength of your words. I know how good—how more than good—you have been; but, at the same time, I feel she is my little sister, and Irene has taken her away."

"For the present, I grant it, and I am sorry; but not for always. Let her have her back now, for a time at least—to-night at any rate."

"Very well, you must manage it your own way."

Poor Miss Frost wrung her hands in nervous terror. She thought of that awful moment when she had swallowed the wood-lice. She thought of the terrible appearance of James when the wasps had stung him. She remembered another occasion when she had found a leech in her bed. Oh, how terrible Irene had been! And there was Miss Carter, who had nearly lost her life in the boat. Then there was Hughie—something very queer had happened to Hughie on one occasion, only Hughie was no coward. He was brave and practical. But then, again, there was Irene herself—Irene so altered, so sweet to little Agnes, so kind about Hughie. Poor Miss Frost was so torn between her diverse emotions that she scarcely knew what to do.

Meanwhile Rosamund had gone into the room. She made a slight noise, and Agnes, only half-asleep, opened her dark eyes and fixed them on Rosamund's face.

"What is it? Is there a toad in the room?" she said.

"Don't be silly, Agnes," said Rosamund. "I really have no patience with you. Now, what is the matter? Sit up in bed and tell me."

Rosamund did not mean to be unkind, nor did she speak in an unkind way, although her words sounded somewhat determined.

"I want to speak to you, Agnes," she said. "You were told stories—and very exaggerated they doubtless were—by Lucy Merriman when Irene and I were at The Follies to-day."

"I was told frightful stories all about Irene."

"Then do you mean to tell me you don't love her any more?"

"I shall always love her; but if she were to do such a thing to me it would kill me."

"She would never do such a thing to you. Now, I will tell you something about her. She used to be a wild and very naughty child. People were afraid of her, and she had nothing else to occupy her time but to add to their terrors. Then I came across her path, and I was not a bit afraid of her. In short, I think I helped her not to be so naughty. But I did not do half the good you have done."

"I?" said little Agnes, in amazement.

"Yes, you, Aggie—you; for you loved her, and you helped her to be good by simply trusting her, and by clinging to her and thinking her all that is good and beautiful. Between us—you and me—we were softening her, and she will be a splendid woman some day, not a poor, miserable wretch, half-wild, but good and true and noble."

"I like women of that sort," said little Agnes, in a fervor of enthusiasm.

"And that is what your own Irene will be, provided that you do not give her up."

"I give her up?" said little Agnes. "But I never will."

"You gave her up to-night when you refused to sleep in the room with her. She is in my room now, trembling all over, terrified, grieved, amazed. Oh, Aggie, why did you do it?"

"I was frightened," whispered Agnes. "I suppose I am a coward."

"You certainly are a very great coward, and I am surprised at you, for Irene would no more hurt you than a mother would her own little child. You have got to come back to her in my arms, and you have got to tell her that you love her more than ever, and that you trust her more than ever. Now, will you or will you not? If you will not, I believe that all our efforts will be fruitless, and Irene will become just as bad as ever. But if you do, you will have done a brave and noble act. You are not a coward, Agnes; you are a girl with a good deal of character, when all is said and done, and you ought to exercise it now for your friend. Just think what she has done for you. Think what she has done for your sister, and"——

"It was to Emmie that she gave the awful wood-lice," said Agnes.

"She did it as an ignorant girl, not in the least knowing the danger and the naughtiness of her own trick. I do not pretend to defend her; but she would not do such a thing now to anybody, and certainly not to you. And yet, because you hear a few bad stories about her, you give up the girl who has sheltered and loved and petted you; who has influenced Lady Jane to make your brother a gentleman, not a shopman; who will help you all through your life, as you, darling, are helping her. Oh! I know you are a little girl, and cannot understand perhaps all that I say; but if you give Irene up to-night I shall be in despair."

Tears came to Rosamund's bright eyes. She sat quite still, looking at the child.

"I won't give her up! I won't be frightened at all. I will run back to her now."

"There's a darling! Go this very second. Where are your slippers? Here is your little blue dressing-gown. You will find her in my room. I won't go back for a minute or two, for I will explain to Frosty. Now, off with you, and remember that I am close to you; but you needn't even think of that, for Irene herself would fight the fiercest and most savage creature to shield and protect you, little Agnes."

It seemed to little Agnes as Rosamund spoke that the terrors that Lucy's words had inspired rolled away as though they had never existed. The brightness came back to her pretty dark eyes. She put her small feet into her little felt slippers, wrapped herself round with her little blue dressing-gown, and ran down the corridor. It was too late for any of the girls to be up, and the corridor was deserted. Lucy had gone to bed, to wrestle and cry and wonder by what possible means she could revenge herself on Rosamund Cunliffe.

Irene was sitting in Rosamund's room, feeling more and more that wild living thing inside her—that wild thing that would not be subdued, that would rise up and urge her to desperate actions. Then all of a sudden there came the patter of small feet, and those feet stopped, not at Rosamund's door, but at her own. It was opened and a little face peeped in. Irene, in Rosamund's room, could not see the face, but she heard the sound, and her heart seemed to stand still. She rose softly, opened the door of communication between the two rooms, and peeped in.

With a cry, Agnes flew to her side.

"Oh, Irene! I have come back. I couldn't sleep in Frosty's bed. I thought—I did think—oh, don't ask me any questions! Just let me sleep with you to-night. And oh, Irene, don't be angry with me!"

"I angry with you?" said Irene, melted on the spot. "No, I won't ask a single question, you sweet, you dear, you treasure! Yes, we will sleep together. Yes, little Agnes, I love you with all my heart for ever and for ever."

CHAPTER XXV. REVENGE.After this incident there was peace in the school for some time; Lucy was defeated. Agnes was more Irene's chosen chum and adored little friend than ever. The child seemed to have completely lost her terrors, and she gave Miss Frost rather less than more of her society. Rosamund watched in silent trepidation. If only Lucy would not interfere! But she did not trust Lucy, nor did she trust another girl in the school, Phyllis Flower, who—small, thin, plain, but clever—had suddenly become Lucy's right-hand. At first Phyllis had rather shrunk away from Lucy, but now she was invariably with her. They talked a good deal, and in low tones, as though they had a great many secrets which they shared each with the other. On one occasion, towards mid-term, when all the girls had settled comfortably to their tasks and life seemed smooth and harmonious once more, even Irene being no longer regarded with dislike and terror by the rest of the girls, Lucy Merriman and Phyllis Flower took a walk together.

"I am very glad we have this chance of being alone," said Lucy, "for I want to speak to you."

"What do you want to say?" asked Phyllis. She was flattered by Lucy's confidence, for some of the girls admired this prim though rather handsome girl very much. Besides, was she not the daughter of their own master and mistress? Had she not a sort of position in the school which the rest of them would have envied a good deal? Lucy was beginning to exercise her power in more than one direction, and she and Rosamund between them really headed two parties in the small school. Of course, Phyllis Flower belonged altogether to Lucy's party.

"Well, what is it?" she said. "What do you want to say to me?"

"It is this," said Lucy. "I am quite determined to have my revenge on that horrid Rosamund and that odious Irene."

"I wish you wouldn't think so much about them. They are quite happy now, and don't do anybody any special harm."

"But that is just it. Rosamund ought never to have been readmitted to the school, and Irene is not the sort of girl who should have come here."

"Well, she seems a very nice sort—not that I know much about her."

"You had better not say that again in my presence, Phyllis—that is, if you wish me to remain your friend."

"Then I won't, dear," said Phyllis, "for certainly I do wish you to be my friend."

"I hate Irene," said Lucy, "and I hate Rosamund, and I hate that little sneak Agnes Frost, who tries to worm herself into everybody's good favor."

"Oh, no, she doesn't! She thinks of no one in all the world but Irene."

"I am surprised at that," said Lucy. "I imagined I had put a spoke in that wheel. I was very much amazed when I saw them thicker than ever the very next day. She is the sort of child who would tell tales out of school. I know the sort—detestable! She is a little pitcher with long ears. She is all that is vulgar and second-rate."

"Perhaps

Comments (0)