All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

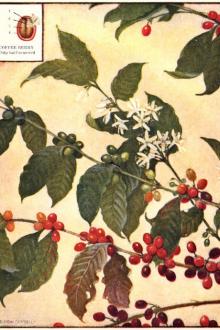

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

Great Britain began the development of coffee cultivation in its colonies in 1730. Parliament first reduced the inland duties. In many ways it has since sought to encourage British-grown coffee, building up a favoritism for it that is still reflected in Mincing Lane quotations. The Netherlands government did the same thing for Java and Sumatra; and France rendered a similar service to her own colonies.

Since Porto Rico became a part of the United States, several attempts have been made by the island government and the planters to popularize Porto Rico coffee in the United States. Scott Truxtun opened a government agency in New York in 1905. Acting upon the counsel and advice of the author, he prosecuted for several years a vigorous campaign in behalf of the Porto Rico Planters' Protective Association. The method followed for coffee was to appoint official brokers, and to certify the genuineness of the product. Owing to insufficient funds and the number of different products for which publicity was sought, the coffee campaign was only moderately successful.

Mortimer Remington, formerly with the J. Walter Thompson Company, a New York advertising agency, was appointed in 1912 commercial agent for the Porto Rico Association, composed of island producers and merchants. Some effective advertising in behalf of Porto Rico coffee was done in the metropolitan district, where a number of high-class grocers were prevailed upon to stock the product, which was packed under seal of the association. As before, however, the other products handled—including cigars, grape-fruit, pineapples, etc.—handicapped the work on coffee, and the enterprise was abandoned. Subsequent efforts by the Washington government to assist the Porto Ricans in evolving a practical plan to extend their coffee market in the United States came to naught because of too much "politics."

Beginning with the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, the government of Guatemala started a propaganda for its coffee in the United States; as the European market, which had up till then absorbed seventy-five percent of its product, was closed to it, owing to the World War. E.H. O'Brien, a coffee broker of San Francisco, directed the publicity. Some full pages were used in newspapers, but the main efforts were directed at the coffee-roasting trade. The campaign, so far as it went, was highly successful.

Costa Rica also gave special encouragement to coffee-trade interests that offered to expand the United States market for Costa Rica coffee during the World War.

For many years Colombia has been talking of making propaganda here for its coffee, but thus far nothing of a constructive character has been done.

São Paulo began in 1908 to make propaganda for its coffee by subsidizing companies and individuals in consuming countries to promote consumption of the Brazil product. A contract was entered into between the state of São Paulo and the coffee firms of E. Johnston & Company and Joseph Travers & Son, of London, to exploit Brazil coffee in the United Kingdom. Similar contracts were made with coffee firms in other European countries, notably in Italy and France. The subsidies were for five years and took the form of cash and coffee. The English company was known as the "State of São Paulo (Brazil) Pure Coffee Company, Ltd." Fifty thousand pounds sterling was granted this enterprise, which roasted and packed a brand known as "Fazenda;" promoted demonstrations at grocers' expositions; and advertised in somewhat limited fashion. The general effect upon the consumption of coffee in England was negligible, however, although at one time some five thousand grocers were said to have stocked the Fazenda brand. A feature of this propaganda was the use of the Tricolator (an American device since better known in the United States) to insure correct making of the beverage, Brazil also made propaganda for its coffee in Japan, in 1915, as part of certain undertakings involving the immigration of Japanese laborers to Brazil.

The Comité Français du Café was formed in Paris in July, 1921, to co-operate with Brazil in an enterprise designed to increase the consumption of coffee in France.

The chief fault in most of the coffee propagandas here and abroad has been the doubtful practise of subsidizing particular coffee concerns instead of spending the funds in a manner designed to distribute the benefits among the trade as a whole. This mistake, and local politics in the producing countries, have made for ultimate failure. A notable exception is the latest propaganda for Brazil coffee in the United States, where all the various interests, the the São Paulo government, the growers, exporters, importers, roasters, jobbers, and dealers, have co-operated in a plan of campaign to advertise coffee per se, and not to secure special privilege to any individual, house, or group.

Joint Coffee Trade Publicity Campaign

Twenty years ago the author began an agitation for co-operative advertising, by the coffee trade. He suggested as a slogan, "Tell the truth about coffee;" and it is gratifying to find that many of his original ideas have been embodied in the present joint coffee trade publicity campaign, now in its fourth year.

The coffee roasters at first were slow to respond to the co-operative advertising suggestion, because in those days competition was more unenlightened than now, and therefore more ruthless. It needed organization to bring the trade to a better understanding of the benefits certain to be shared by all when their individual interests were pooled in a common cause. Leaders of the best thought in the trade, however, were quick to realize that only by united effort was it possible to achieve real progress; and when it was suggested that the first step was to organize the roasting trade, the idea took so firm a hold that it only needed some one to start it to bring together in one combination the keenest minds in the business.

The coffee roasters organized their national association in 1911. The author of this work urged that co-operative advertising based upon scientific research should be done by the roasters themselves independently of the growers; but it was found impracticable to unite diverging interests on such an issue, and so the leaders of the movement bent all their energies toward promoting a campaign that would be backed jointly by growers and distributers, since both would receive equal benefit from any resulting increase in consumption. Brazil, the source of nearly three-quarters of the world's coffee, was the logical ally; and an appeal was made to the planters of that country. A party of ten leading United States roasters and importers visited Brazil in 1912 at the invitation of the federal government.

In Brazil, as in the United States, progress resulted from organization. The planters of the state of São Paulo, who produce more than one-half of all coffee used in the United States, were the first to appreciate the propaganda idea. After their attempts to interest the national government failed, the São Paulo coffee men founded the Sociedade Promotora da Defesa do café (Society to Promote the Defense of Coffee), and persuaded their state legislature to pass a law taxing every bag of coffee shipped from the plantations of that state in a period of four years. This tax, amounting to one hundred reis per bag of 132 pounds, or about two and one-half cents United States money at even exchange rates, is collected by the railroads from the shippers, and turned over to the Sociedade.

The Brazilian Society sent to the United States a special envoy, Theodore Langgaard de Menezes, to conclude arrangements; and on March 4, 1918, in New York, the pact was signed whereby São Paulo was to contribute to the publicity campaign in the United States approximately $960,000 at the rate of $240,000 a year for four years; and the members of the trade in the United States were to contribute altogether $150,000[346]. The success of the negotiations was due to the skilful management of Ross W. Weir in the United States, and to the superior salesmanship of Louis R. Gray, the Arbuckle representative in Brazil.

JOINT COFFEE TRADE PUBLICITY COMMITTEE IN UNITED STATES

Supervision of the advertising in the United States was delegated to five men, representing both the importing and roasting branches of the trade, and designated as the Joint Coffee Trade Publicity Committee of the United States. Three of these committeemen, Ross W. Weir, of New York; F.J. Ach, of Dayton, Ohio; and George S. Wright, of Boston, are roasters; and two, William Bayne, Jr., and C.H. Stoffregen, both of New York, are importers and jobbers, or green-coffee men. The committee organized with Mr. Weir as chairman, Mr. Wright as treasurer, and Mr. Stoffregen as secretary. At the invitation of the committee, C.W. Brand of Cleveland, then president of the National Coffee Roasters Association, attended committee meetings, and assisted in determining the policies of the campaign. Headquarters were established at 74 Wall Street, in the heart of the New York coffee district, with Felix Coste as secretary-manager, and Allan P. Ames as publicity director. N.W. Ayer & Son, advertising agents of Philadelphia, who had engineered the plan of campaign from the start of the movement in the National Coffee Roasters Association, handle the advertising account.

São Paulo's contribution to the advertising fund is sent in monthly instalments to the Joint Coffee Trade Publicity Committee under an agreement that it shall be expended only for magazine and newspaper space.

COPY THAT STRESSED THE HEALTHFULNESS OF COFFEE, 1919–1920 COPY THAT STRESSED THE HEALTHFULNESS OF COFFEE, 1919–1920

Supplementing this Brazilian contribution, is the fund raised by voluntary subscriptions from the coffee trade of the United States on the basis of one cent per bag handled annually. This American fund is used for the expenses of administration, for educational advertising outside of magazine and newspaper space, and for various kinds of trade promotion and dealer stimulation.

The first advertising appeared in April, 1919, in 306 leading newspapers in 182 large cities, with a total circulation of more than 16,000,000. The cities chosen represented all the centers of wholesale coffee distribution.

Magazine advertising began in June of the same year, using twenty-one periodicals, all of national circulation. This list has been changed from time to time to meet the special needs of the campaign.

More than fifty grocery-trade magazines have carried the committee's dealer advertising, although not all of these have been used continuously. Every part of the country was represented on the trade-paper list.

Full pages have been run each month in nine of the leading national medical journals. These advertisements were written by a physician of national reputation. Under the caption, "The Case for Coffee," these advertisements have discussed the properties of coffee from the physiological standpoint, and have asked the doctors to judge it fairly.

From the start the committee's advertising has been broadly educational. The properties of coffee have been discussed; charges against coffee have been answered. The housekeeper has been told how to get the best results from the coffee she buys; hotel and restaurant proprietors have been reminded that many of them owe their prosperity largely to a reputation for serving good coffee; new uses have been exploited for coffee, as a flavoring agent for desserts and other sweets; employers have been taught the important service good coffee may render in increasing the comfort and efficiency

Comments (0)