All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

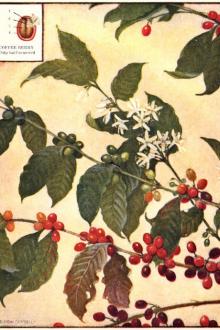

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

In Portuguese East Africa, the natives prepare and drink coffee after the approved African native fashion, but the white population follows European customs. In the Union of South Africa, Dutch and English customs prevail in making and serving the beverage.

Manners and Customs in Asia

"Arabia the Happy" deserves to be called "the Blest", if only for its gift of coffee to the world. Here it was that the virtues of the drink were first made known; here the plant first received intensive cultivation. After centuries of habitual use of the beverage, we find the Arabs, now as then, one of the strongest and noblest races of the world, mentally superior to most of them, generally healthy, and growing old so gracefully that the faculties of the mind seldom give way sooner than those of the body. They are an ever living earnest of the healthfulness of coffee.

The Arabs are proverbially hospitable; and the symbol of their hospitality for a thousand years has been the great drink of democracy—coffee. Their very houses are built around the cup of human brotherhood. William Wallace,[366] writing on Arabian philosophy, manners, and customs, says:

The principal feature of an Arab house is the kahwah or coffee room. It is a large apartment spread with mats, and sometimes furnished with carpets and a few cushions. At one end is a small furnace or fireplace for preparing coffee. In this room the men congregate; here guests are received, and even lodged; women rarely enter it, except at times when strangers are unlikely to be present. Some of these apartments are very spacious and supported by pillars; one wall is usually built transversely to the compass direction of the Ka'ba (sacred shrine of Mecca). It serves to facilitate the performance of prayer by those who may happen to be in the kahwah at the appointed times.

Several rounds of coffee, without milk or sugar, but sometimes flavored with cardamom seeds, are served to the guest at first welcome; and coffee may be had at all hours between meals, or whenever the occasion demands it. Always the beans are freshly roasted, pounded, and boiled. The Arabs average twenty-five to thirty cups (findjans) a day. Everywhere in Arabia there are to be found cafés where the beverage may be bought.

Ships of the Desert Laden with Coffee, Arabia

Those of the lower classes are thronged throughout the day. In front, there is generally a porch or bench where one may sit. The rooms, benches, and little chairs lack the cleanliness and elegance of the one-time luxurious "caffinets" of cities like Damascus and Constantinople, but the drink is the same. There is not in all Yemen a single market town or hamlet where one does not find upon some simple hut the legend, "Shed for drinking coffee".

The Arab drinks water before taking coffee, but never after it. "Once in Syria", says a traveler, "I was recognized as a foreigner because I asked for water just after I had taken my coffee. 'If you belonged here', said the waiter, 'you would not spoil the taste of coffee in your mouth by washing it away with water.'"

It is an adventure to partake of coffee prepared in the open, at a roadside inn, or khan, in Arabia by an araba, or diligence driver. He takes from his saddle-bag the ever-present coffee kit, containing his supply of green beans, of which he roasts just sufficient on a little perforated iron plate over an open fire, deftly taking off the beans, one at a time, as they turn the right color. Then he pounds them in a mortar, boils his water in the long, straight-handled open boiler, or ibrik (a sort of brass mug or jezveh), tosses in the coffee powder, moving the vessel back and forth from the fire as it boils up to the rim; and, after repeating this maneuver three times, pours the contents foaming merrily into the little egg-like serving cups.

Cafée sultan, or kisher, the original decoction, made from dried and toasted coffee hulls, is still being drunk in parts of Arabia and Turkey.

Coffee in Arabia is part of the ritual of business, as in other Oriental countries. Shop-keepers serve it to the customer before the argument starts. Recently, a New York barber got some valuable publicity because he regaled his customers with tea and music. It was "old stuff". The Arabian and Turkish barber shops have been serving coffee, tobacco, and sweetmeats to their customers for centuries.

For a faithful description of the ancient coffee ceremony of the Arabs, which, with slight modification, is still observed in Arabian homes, we turn to Palgrave. First he describes the dwelling and then the ceremony:

The K'hāwah was a large oblong hall, about twenty feet in height, fifty in length, and sixteen, or thereabouts, in breadth; the walls were coloured in a rudely decorative manner with brown and white wash, and sunk here and there into small triangular recesses, destined to the reception of books, though of these Ghafil at least had no over-abundance, lamps, and other such like objects. The roof of timber, and flat; the floor was strewed with fine clean sand, and garnished all round alongside of the walls with long strips of carpet, upon which cushions, covered with faded silk, were disposed at suitable intervals. In poorer houses felt rugs usually take the place of carpets.

In one corner, namely, that furthest removed from the door, stood a small fireplace, or, to speak more exactly, furnace, formed of a large square block of granite, or some other hard stone, about twenty inches each way; this is hollowed inwardly into a deep funnel, open above, and communicating below with a small horizontal tube or pipe-hole, through which the air passes, bellows-driven, to the lighted charcoal piled up on a grating about half-way inside the cone. In this manner the fuel is soon brought to a white heat, and the water in the coffee-pot placed upon the funnel's mouth is readily brought to boil. The system of coffee furnaces is universal in Djowf and Djebel Shomer, but in Nejed itself, and indeed in whatever other yet more distant regions of Arabia I visited to the south and east, the furnace is replaced by an open fireplace hollowed in the ground floor, with a raised stone border, and dog-irons for the fuel, and so forth, like what may be yet seen in Spain. This diversity of arrangement, so far as Arabia is concerned, is due to the greater abundance of firewood in the south, whereby the inhabitants are enabled to light up on a larger scale; whereas throughout the Djowf and Djebel Shomer wood is very scarce, and the only fuel at hand is bad charcoal, often brought from a considerable distance, and carefully husbanded.

This corner of the K'hāwah is also the place of distinction whence honour and coffee radiate by progressive degrees round the apartment, and hereabouts accordingly sits the master of the house himself, or the guests whom he more especially delighteth to honour.

On the broad edge of the furnace or fireplace, as the case may be, stands an ostentatious range of copper coffee-pots, varying in size and form. Here in the Djowf their make resembles that in vogue at Damascus; but in Nejed and the eastern districts they are of a different and much more ornamental fashioning, very tall and slender, with several ornamental circles and mouldings in elegant relief, besides boasting long beak-shaped spouts and high steeples for covers. The number of these utensils is often extravagantly great. I have seen a dozen at a time in a row by one fireside, though coffee-making requires, in fact, only three at most. Here in the Djowf five or six are considered to be the thing; for the south this number must be doubled; all this to indicate the riches and munificence of their owner, by implying the frequency of his guests and the large amount of coffee that he is in consequence obliged to have made for them.

Behind this stove sits, at least in wealthy houses, a black slave, whose name is generally a diminutive in token of familiarity or affection; in the present case it was Soweylim, the diminutive of Sālim. His occupation is to make and pour out the coffee; where there is no slave in the family, the master of the premises himself, or perhaps one of his sons, performs that hospitable duty; rather a tedious one, as we shall soon see.

We enter. On passing the threshold it is proper to say, "Bismillah, i.e., in the name of God;" not to do so would be looked on as a bad augury alike for him who enters and for those within. The visitor next advances in silence, till on coming about half-way across the room, he gives to all present, but looking specially at the master of the house, the customary "Es-salamu'aleykum," or "Peace be with you," literally, "on you." All this while every one else in the room has kept his place, motionless, and without saying a word. But on receiving the salaam of etiquette, the master of the house rises, and if a strict Wahhābee, or at any rate desirous of seeming such, replies with the full-length traditionary formula. "W' 'aleykumu-s-salāmu, w'rahmat' Ullahi w'barakátuh," which is, as every one knows, "And with (or, on) you be peace, and the mercy of God, and his blessings." But should he happen to be of anti-Wahhābee tendencies the odds are that he will say "Marhaba," or "Ahlan w' sahlan," i.e., "welcome" or "worthy, and pleasurable," or the like; for of such phrases there is an infinite, but elegant variety.

All present follow the example thus given, by rising and saluting. The guest then goes up to the master of the house, who has also made a step or two forwards, and places his open hand in the palm of his host's, but without grasping or shaking, which would hardly pass for decorous, and at the same time each repeats once more his greeting, followed by the set phrases of polite enquiry, "How are you?" "How goes the world with you?" and so forth, all in a tone of great interest, and to be gone over three or four times, till one or other has the discretion to say "El hamdu l'illāh," "Praise be to God", or, in equivalent value, "all right," and this is a signal for a seasonable diversion to the ceremonious interrogatory.

The guest then, after a little contest of courtesy, takes his seat in the honoured post by the fireplace, after an apologetical salutation to the black slave on the one side, and to his nearest neighbour on the other. The best cushions and newest looking carpets have been of course prepared for his honoured weight. Shoes or sandals, for in truth the latter alone are used in Arabia, are slipped off on the sand just before reaching the carpet, and there they remain on the floor close by. But the riding stick or wand, the inseparable companion of every true Arab, whether Bedouin or

Comments (0)