All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

The coffee tree, scientifically known as Coffea arabica, is native to Abyssinia and Ethiopia, but grows well in Java, Sumatra, and other islands of the Dutch East Indies; in India, Arabia, equatorial Africa, the islands of the Pacific, in Mexico, Central and South America, and the West Indies. The plant belongs to the large sub-kingdom of plants known scientifically as the Angiosperms, or Angiospermæ, which means that the plant reproduces by seeds which are enclosed in a box-like compartment, known as the ovary, at the base of the flower. The word Angiosperm is derived from two Greek words, sperma, a seed, and aggeion, pronounced angeion, a box, the box referred to being the ovary.

This large sub-kingdom is subdivided into two classes. The basis for this division is the number of leaves in the little plant which develops from the seed. The coffee plant, as it develops from the seed, has two little leaves, and therefore belongs to the class Dicotyledoneæ. This word dicotyledoneæ is made up of the two Greek words, di(s), two, and kotyledon, cavity or socket. It is not necessary to see the young plant that develops from the seed in order to know that it had two seed leaves; because the mature plant always shows certain characteristics that accompany this condition of the seed.

In every plant having two seed leaves, the mature leaves are netted-veined, which is a condition easily recognized even by the layman; also the parts of the flowers are in circles containing two or five parts, but never in threes or sixes. The stems of plants of this class always increase in thickness by means of a layer of cells known as a cambium, which is a tissue that continues to divide throughout its whole existence. The fact that this cambium divides as long as it lives, gives rise to a peculiar appearance in woody stems by which we can, on looking at the stem of a tree of this type when it has been sawed across, tell the age of the tree.

In the spring the cambium produces large open cells through which large quantities of sap can run; in the fall it produces very thick-walled cells, as there is not so much sap to be carried. Because these thin-walled open cells of one spring are next to the thick-walled cells of the last autumn, it is very easy to distinguish one year's growth from the next; the marks so produced are called annual rings.

We have now classified coffee as far as the class; and so far we could go if we had only the leaves and stem of the coffee plant. In order to proceed farther, we must have the flowers of the plant, as botanical classification goes from this point on the basis of the flowers. The class Dicotyledoneæ is separated into sub-classes according to whether the flower's corolla (the showy part of the flower which ordinarily gives it its color) is all in one piece, or is divided into a number of parts. The coffee flower is arranged with its corolla all in one piece, forming a tube-shaped arrangement, and accordingly the coffee plant belongs to the sub-class Sympetalæ, or Metachlamydeæ, which means that its petals are united.

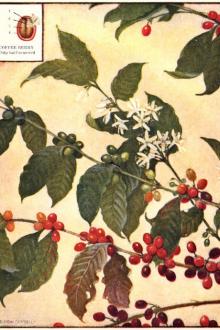

From a drawing by Ch. Emonts in Jardin's Le Caféier et Le Café

The next step in classification is to place the plant in the proper division under the sub-class, which is the order. Plants are separated into orders according to their varied characteristics. The coffee plant belongs to an order known as Rubiales. These orders are again divided into families. Coffee is placed in the family Rubiaceæ, or Madder Family, in which we find herbs, shrubs or trees, represented by a few American plants, such as bluets, or Quaker ladies, small blue spring flowers, common to open meadows in northern United States; and partridge berries (Mitchella repens).

The Madder Family has more foreign representatives than native genera, among which are Coffea, Cinchona, and Ipecacuanha (Uragoga), all of which are of economic importance. The members of this family are noted for their action on the nervous system. Coffee, as is well known, contains an active principle known as caffein which acts as a stimulant to the nervous system and in small quantities is very beneficial. Cinchona supplies us with quinine, while Ipecacuanha produces ipecac, which is an emetic and purgative.

The families are divided into smaller sections known as genera, and to the genus Coffea belongs the coffee plant. Under this genus Coffea are several sub-genera, and to the sub-genus Eucoffea belongs our common coffee, Coffea arabica. Coffea arabica is the original or common Java coffee of commerce. The term "common" coffee may seem unnecessary, but there are many other species of coffee besides arabica. These species have not been described very frequently; because their native haunts are the tropics, and the tropics do not always offer favorable conditions for the study of their plants.

All botanists do not agree in their classification of the species and varieties of the coffea genus. M.E. de Wildman, curator of the royal botanical gardens at Brussels, in his Les Plantes Tropicales de Grande Culture, says the systematic division of this interesting genus is far from finished; in fact, it may be said hardly to be begun.

Coffea arabica we know best because of the important rôle it plays in commerce.

The coffee plant most cultivated for its berries is, as already stated, Coffea arabica, which is found in tropical regions, although it can grow in temperate climates. Unlike most plants that grow best in the tropics, it can stand low temperatures. It requires shade when it grows in hot, low-lying districts; but when it grows on elevated land, it thrives without such protection. Freeman[94] says there are about eight recognized species of coffea.

From a drawing by Ch. Emonts in Jardin's Le Caféier et Le Café

Coffea Arabica

Coffea arabica is a shrub with evergreen leaves, and reaches a height of fourteen to twenty feet when fully grown. The shrub produces dimorphic branches, i.e., branches of two forms, known as uprights and laterals. When young, the plants have a main stem, the upright, which, however, eventually sends out side shoots, the laterals. The laterals may send out other laterals, known as secondary laterals; but no lateral can ever produce an upright. The laterals are produced in pairs and are opposite, the pairs being borne in whorls around the stem. The laterals are produced only while the joint of the upright, to which they are attached, is young; and if they are broken off at that point, the upright has no power to reproduce them. The upright can produce new uprights also; but if an upright is cut off, the laterals at that position tend to thicken up. This is very desirable, as the laterals produce the flowers, which seldom appear on the uprights. This fact is utilized in pruning the coffee tree, the uprights being cut back, the laterals then becoming more productive. Planters generally keep their trees pruned down to about six feet.

The leaves are lanceolate, or lance-shaped, being borne in pairs opposite each other. They are three to six inches in length, with an acuminate apex, somewhat attenuate at the base, with very short petioles which are united with the short interpetiolar stipules at the base. The coffee leaves are thin, but of firm texture, slightly coriaceous. They are very dark green on the upper surface, but much lighter underneath. The margin of the leaf is entire and wavy. In some tropical countries the natives brew a coffee tea from the leaves of the coffee tree.

The coffee flowers are small, white, and very fragrant, having a delicate characteristic odor. They are borne in the axils of the leaves in clusters, and several crops are produced in one season, depending on the conditions of heat and moisture that prevail in the particular season. The different blossomings are classed as main blossoming and smaller blossomings. In semi-dry high districts, as in Costa Rica or Guatemala, there is one blossoming season, about March, and flowers and fruit are not found together, as a rule, on the trees. But in lowland plantations where rain is perennial, blooming and fruiting continue practically all the year; and ripe fruits, green fruits, open flowers, and flower buds are to be found at the same time on the same branchlet, not mixed together, but in the order indicated.

The flowers are also tubular, the tube of the corolla dividing into five white segments. Dr. P.J.S. Cramer, chief of the division of plant breeding, Department of Agriculture, Netherlands India, says the number of petals is not at all constant, not even for flowers of the same tree. The corolla segments are about one-half inch in length, while the tube itself is about three-eighths of an inch long. The anthers of the stamens, which are five in number, protrude from the top of the corolla tube, together with the top of the two-cleft pistil. The calyx, which is so small as to escape notice unless one is aware of its existence, is annular, with small, tooth-like indentations.

While the usual color of the coffee flower is white, the fresh stamens and pistils may have a greenish tinge, and in some cultivated species the corolla is pale pink.

The size and condition of the flowers are entirely dependent on the weather. The flowers are sometimes very small, very fragrant, and very numerous; while at other times, when the weather is not hot and dry, they are very large, but not so numerous. Both sets of flowers mentioned above "set fruit," as it is called; but at times, especially in a very dry season, they bear flowers that are few in number, small, and imperfectly formed, the petals frequently being green instead of white. These flowers do not set fruit. The flowers that open on a dry sunny day show a greater yield of fruit than those that open on a wet day, as the first mentioned have a better chance of being pollinated by the insects and the wind. The beauty of a coffee estate in flower is of a very fleeting character. One day it is a snowy expanse of fragrant white blossoms for miles and miles, as far as the eye can see, and two days later it reminds one of the lines from Villon's Des Dames du Temps Jadis.

Where are the snows of yesterday?

The winter winds have blown them all away.

But here, the winter winds are not to blame: the soft, gentle breezes of the perpetual summer have wrought the havoc, leaving, however, a not unpleasing picture of dark, cool, mossy green foliage.

The flowers are beautiful, but the eye of the planter sees in them not alone beauty and fragrance. He looks far beyond, and in his mind's eye he sees bags and bags of green coffee, representing to him the goal and reward of all his toil. After the flowers droop, there appear

Comments (0)