All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

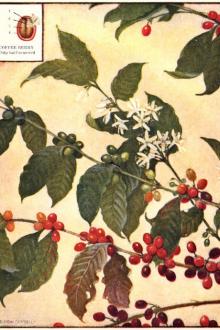

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

Coffee Drinking in the United States

Is the United States using more coffee than formerly, allowing for the increase in population? Of course there are sporadic increases, in particular years and groups of years, and they may indicate to the casual observer that our coffee drinking is mounting rapidly. And then there is the steadily growing import figure, double what it was within the memory of a man still young.

Import price and per capita consumption of coffee in the United States for the fiscal years 1851 to 1914, in five-year averages. Solid line represents import price per pound. Dotted line represents per capita consumption

But the apparent growth in any given year is a matter of comparison with a nearby year, and there are declines as well as jumps; and, as for the gradual growth, it must always be remembered that, according to the Census Bureau, some 1,400,000 more people are born into this country every year, or enter its ports, than are removed by death or emigration. At the present rate this increase would account for about 17,000,000 pounds more coffee each year than was consumed in the year before.

The question is: Do Mr. Citizen, or Mrs. Citizen, or the little Citizens growing up into the coffee-drinking age, pass his or her or their respective cups along for a second pouring where they used to be satisfied with one, or do they take a cup in the evening as well as in the morning, or do they perhaps have it served to them at an afternoon reception where they used to get something else? In other words, is the coffee habit becoming more intensive as well as more extensive?

There are plenty of very good reasons why it should have become so in the last twenty-five or thirty years; for the improvements in distributing, packing, and preparing coffee have been many and notable. It is a far cry these days from the times when the housewife snatched a couple of minutes amid a hundred other kitchen duties to set a pan over the fire to roast a handful of green coffee beans, and then took two or three more minutes to pound or grind the crudely roasted product into coarse granules for boiling.

For a good many years, the keenest wits of the coffee merchants, not only of the United States but of Europe as well, have been at work to refine the beverage as it comes to the consumer's cup; and their success has been striking. Now the consumer can have his favorite brand not only roasted but packed air-tight to preserve its flavor; and made up, moreover, of growths brought from the four corners of the earth and blended to suit the most exacting taste. He can buy it already ground, or he can have it in the form of a soluble powder; he can even get it with the caffein element ninety-nine percent removed. It is preserved for his use in paper or tin or fiber boxes, with wrappings whose attractive designs seem to add something in themselves to the quality. Instead of the old coffee pot, black with long service, he has modern shining percolators and filtration devices; with a new one coming out every little while, to challenge even these. Last but not least, he is being educated to make it properly—tuition free.

It would be surprising, with these and dozens of other refinements, if a far better average cup of coffee were not produced than was served forty years ago, and if the coffee drinker did not show his appreciation by coming back for more.

As a matter of fact, the figures show that he does come back for more. We do not refer to the figures of the last two years, which indeed are higher than those for many preceding years, but to the only averages that are of much significance in this connection; namely, those for periods of years going back half a century or more. Five-year averages back to the Civil War show increasing per capita consumption for continental United States (see table).

Five-Year Per Capita Consumption Figures Five-year

Period Per capita

Five-year

Period Per capita

1867–71 6.38 1897–1901 10.52 1872–76 7.03 1902–06 11.50 1877–81 7.53 1907–11 10.21 1882–86 9.09 1912–16 10.02 1887–91 8.07 1917–21 11.39 1892–96 8.63

It will be seen that the gain has been a decided one, fairly steady, but not exactly uniform. In the fifty years, John Doe has not quite come to the point where he hands up his cup for a second helping and keeps a meaningful silence. Instead, he stipulates, "Don't fill it quite full; fill it about five-sixths as full as it was before." That is a substantial gain, and one that the next fifty years can hardly be expected to duplicate, in spite of the efforts of our coffee advertisers, our inventors, and our vigorous importers and roasters.

The most striking feature of this fifty-year growth was the big step upward in 1897, when the per capita rose two pounds over the year before and established an average that has been pretty well maintained since. Something of the sort may have taken place again in 1920, when there was a three-pound jump over the year before. It will be interesting to see whether this is merely a jump or a permanent rise; whether our coffee trade has climbed to a hilltop or a plateau.

In this connection it should be noted that the government's per capita coffee figures apply only to continental United States, and that in computing them all the various items of trade of the non-contiguous possessions (not counting the Philippines, whose statistics are kept entirely separate from those of the United States proper) are carefully taken into account.

But for the benefit of students of coffee figures it should be added that this method does not result in a final figure except for one year in ten. The reason is that between censuses the population of the country is determined only by estimates; and these estimates (by the U.S. Bureau of the Census) are based on the average increase in the preceding census decade. The increase between 1910 and 1920, for instance, is divided by 120, the number of months in the period, and this average monthly increase is assumed to be the same as that of the current year and of other years following 1920. Until new figures are obtained in 1930, the monthly increase will continue to be estimated at the same rate as the increase from 1910 to 1920, or about 118,000. This figure will be used in computing the per capita coffee consumption. But when the 1930 figures are in, it may be found that the estimates were too low or too high, and the per capita figures for all intervening years will accordingly be subject to revision. This will not amount to much, probably five-hundredths of a pound at most; but it is evident that between 1920 and 1930 all per capita consumption figures issued by the government are to be considered as provisional to that extent at least.

In the 1920 Statistical Abstract the government has revised its per capita coffee and tea figures to conform to actual instead of estimated population figures between 1910 and 1920, with the result that these figures are slightly different from those published in previous editions of the Abstract. Figures from 1890 to 1910 have also been slightly changed, as they were originally computed by using population figures as of June 1, whereas it is desirable to have computations based on July 1 estimates to make them conform to present per capita figures.

Reviewing the 1921 Trade in the United States

According to the latest available foreign trade summaries issued by the government, the United States bought more coffee in 1921 than in any previous calendar year of our history, although the total imports did not quite reach the highest fiscal-year mark. Our purchases passed the 1920 mark by more than 40,000,000 pounds and were higher than those of two years ago by 3,500,000 pounds.

But this record was made only in actual amounts shipped, as the value of imported coffee was far below that of immediately preceding years. Coffee values, however, fell off less than the average values for all imports, the decrease for coffee being forty-three percent and for the country's total imports fifty-two percent.

Exports of coffee were somewhat less in quantity than in 1920, and about the same as in 1919; although the value, like that of imports, was considerably less than in either previous year.

Re-exports of foreign coffee were considerably below the 1920 mark, in both quantity and value, and indeed were less than in several years. The amount of tea re-exported to foreign countries was only about half that shipped out in 1920, showing a continuation of the tendency of the United States to discontinue its services as a middleman, which raised the through traffic in tea several million pounds during the dislocation of shipping.

Actual figures of amounts and values of gross coffee imports for the three calendar years, 1919–1921, have been as follows:

This represents a gain of three and three-tenths percent over 1920 in quantity and of only about one-fifth of one percent over 1919. The decrease in value in 1921 was forty-three percent from the figures for 1920 and forty-five percent from those of 1919.

Domestic exports of coffee, mostly from Hawaii and Porto Rico, amounted to 34,572,967 pounds valued at $5,895,606, as compared with 36,757,443 pounds valued at $9,803,574 in the calendar year 1920, or a decrease of six percent in quantity and forty percent in value. In 1919 domestic exports were 34,351,554 pounds, having a value of $8,816,581, practically the same in quantity, but showing a falling off of thirty-three percent in value.

Re-exports of foreign coffee amounted to 36,804,684 pounds in 1921, having a value of $3,911,847, a decline of twenty-five percent from the 49,144,691 pounds of 1920 and of fifty-four percent from the 81,129,691 pounds of 1919; whereas in point of value there was a decrease of fifty-six percent from 1920, which was $9,037,882, and of eighty-eight percent from that of 1919, which was $16,815,468.

The average value per pound of the imported coffee, according to these figures, works out at little more than half that of either 1920 or 1919, illustrating the precipitate drop of prices when the depression came on. The pound value in 1921 was 10.6c.; for 1920, 19.4c.; and for 1919, 19.5c. These values are derived from the valuations placed on shipments at the point of export, the "foreign valuation" for which the much discussed "American valuation" is proposed as a substitute. They accordingly do not take into account costs of freight, insurance, etc.

It is interesting to note that the average valuation of 10.6c. a pound for coffee shipped during the calendar year is a substantial drop from the 13.12c. a pound that was the average for the fiscal year 1921, showing that the decline in values continued during the last half of the calendar year.

Coffee imports in 1921 continued to run in about the same well-worn channels as in previous years, according to the figures showing the trade with the producing countries. The United States, as heretofore, drew almost its whole supply from its neighbors on this side of the globe; the countries to the south furnishing ninety-seven percent of the total entering our ports. The three chief countries of South America contributed eighty-five percent; and the share of Brazil alone was sixty-two and five-tenths percent.

Brazil's progress to her normal pre-war position in our coffee trade is rather slow, although she continues

Comments (0)