Psychology by Robert S. Woodworth (top rated ebook readers .TXT) 📕

[Footnote: A series of waggish critics has evolved the following: "First psychology lost its soul, then it lost its mind, then it lost consciousness; it still has behavior, of a kind."]

The best way of getting a true picture of psychology, and of reaching an adequate definition of its subject-matter, would be to inspect the actual work of psychologists, so as to see what kind of knowledge they are seeking. Such a survey would reveal quite a variety of problems under process of investigation, some of them practical problems, others not directly practical.

Varieties of Psychology

Differential psychology.

One line of question that always interests the beginner in psychology is as to how people differ--how different people act under the same circumstances--and why; and if we watch the professional psychologist, we often find him working at just this problem. He tests a great number of individuals to see how they

Read free book «Psychology by Robert S. Woodworth (top rated ebook readers .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Robert S. Woodworth

- Performer: -

Read book online «Psychology by Robert S. Woodworth (top rated ebook readers .TXT) 📕». Author - Robert S. Woodworth

Injury to the retina or optic nerve, occurring early in life, results in an under-development of the cortex in the occipital lobe. The nerve cells remain small and their dendrites few and meager, because they have not received their normal amount of exercise through stimulation from the eye.

Exercise, then, has the same general effect on neurones that it has on muscles; it causes them to grow and it probably also improves their internal condition so that they act more readily and more strongly. The growth, in the cortex, of dendrites and of the end-brushes of axons that interlace with the dendrites, must improve the synapses between one neurone and another, and thus make better conduction paths between one part of the cortex and another, and also between the cortex and the lower sensory and motor centers.

The law of exercise has thus a very definite meaning when {415} translated into neural terms. It means that the synapses between stimulus and response are so improved, when traversed by nerve currents in the making of a reaction, that nerve currents can get across them more easily the next time.

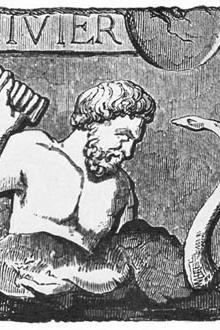

Fig. 63.--The law of exercise in terms of synapse. A nerve current is supposed to pass along this pair of neurones in the direction of the arrow. Every time it passes, it exercises the end-brush and dendrites at the synapse (for the "passage of a nerve current" really means activity on the part of the neurones through which it passes), and the after-effect of this exercise is growth of the exercised parts, and consequent improvement of the synapse as a linkage between one neurone and the other. Repeated exercise may probably bring a synapse from a very loose condition to a state of close interweaving and excellent power of transmitting the nerve current.

The more a synapse is used, the better synapse it becomes, and the better linkage it provides between some stimulus and some response. The cortex is the place where linkages are made in the process of learning, and it is there also that forgetting, or atrophy, takes place through disuse. Exercise makes a synapse closer, disuse lets it relapse into a loose and poorly conducting state.

The law of combination, also, is readily translated into {416} neural terms. The "pre-existing loose linkages" which it assumed to exist undoubtedly do exist in the form of "association fibers" extending in vast numbers from any one part of the cortex to many other parts. These fibers are provided by native constitution, but probably terminate rather loosely in the cortex until exercise has developed them. They may be compared to telephone wires laid down in the cables through the streets and extending into the houses, but still requiring a little fine work to attach them properly to the telephone instruments.

Fig. 64.--Diagram for the learning of the name of an object, transformed into a neural diagram. The vocal movement of saying the name is made in response to the auditory stimulus of hearing the name, but when the neurone in the "speech center" is thus made active, it takes up current also from the axon that reaches it from the visual center, even though the synapse between this axon and the speech neurone is far from close. This particular synapse between the visual and the speech centers, being thus exercised, is left in an improved condition. Each neurone in the diagram represents hundreds in the brain, for brain activities are carried on by companies and regiments of neurones. (Figure text: object seen, visual center name heard, auditory center, speech center, name spoken)

The diagrams illustrating different cases under the law of combination can easily be perfected into neural diagrams, though, to be sure, any diagram is ultra-simple as compared with the great number of neurones that take part in even a simple reaction.

The reader will be curious to know now much of this neural interpretation of our psychological laws is observed fact, and how much speculation. Well, we cannot as yet {417} observe the brain mechanism in actual operation--not in any detail. We have good evidence, as already outlined, for growth of the neurones and their branches through exercise.

Fig. 65.--Control, in multiplying. The visual stimulus of two numbers in a little column, has preformed linkages both with the adding response and with that of multiplying. But the mental set for adding being inactive at the moment, and that for multiplying active (because the subject means to multiply), the multiplying response is facilitated.

We have perfectly good evidence of the law of "unitary response to multiple stimuli" from the physiological study of reflex action; and we have perfectly good anatomical evidence of the convergence and divergence of neural paths of connection, as required by the law of combination. The association fibers extending from one part to another of the cortex are an anatomical fact. [Footnote: See p. 56.] Facilitation is a fact, and that means that a stimulus which could not of itself arouse a response can coöperate with another stimulus that has a direct connection with that response, and reinforce its effect. In short, all the elements required for a neural law of combination are known facts, and the only matter of doubt is whether we have built these elements together aright in our interpretation. It is not pure speculation, by any means.

{418}

EXERCISES1. Outline the chapter, in the form of a list of laws and sub-laws.

2. Review the instances of learning cited in Chapters XIII-XV, and examine whether they are covered and sufficiently accounted for by the general laws given in the present chapter.

3. Draw diagrams, like those given in this chapter, for the simpler cases, at least, that you have considered in question 2.

4. Show that response by analogy is important in the development of language. Consider metaphor, for example, and slang, and the using of an old word in a new sense (as in the case of 'rail-road').

William James devoted much thought to the problem of the mechanism of learning, habit, association, etc., and his conclusions are set forth in several passages in his Principles of Psychology, 1890, Vol. I, pp. 104-112, 554-594, and Vol. II, pp. 578-592.

Another serious consideration of the matter is given by William McDougall in his Physiological Psychology, 1905, Chapters VII and VIII.

See also Thorndike's Educational Psychology, Briefer Course, 1914, Chapter VI.

On the whole subject of association, see Howard C. Warren, A History of the Association Psychology, 1921.

{419}

PERCEPTION

You will remember the case of John Doe, who was brought before us for judgment on his behavior, as to how far it was native and how far acquired. We have since that time been occupied in hearing evidence on the case, and after mature consideration have reached a decision which we may formulate as follows: that this man's behavior is primarily instinctive or native, but that new attachments of stimulus and response, and new combinations of responses, acquired in the process of learning, have furnished him with such an assortment of habits and skilled acts of all sorts that we can scarcely identify any longer the native reactions out of which his whole behavior is built. That decision being reached, we are still not ready to turn the prisoner loose, but wish to keep him under observation for a while longer, in order to see what use he makes of this vast stock of native and acquired reactions. We wish to know how an individual, so equipped, behaves from day to day, and meets the exigencies of life. Such, in brief, is the task we have still before us.

Accordingly, one fine morning we enter our prisoner's sleeping quarters, and find him, for once, making no use of his acquired reactions, as far as we can see, and utilizing but a small fraction of his native reactions. He is, in short, asleep. We ring a bell, and he stirs uneasily. We {420} ring again, and he opens his eyes sleepily upon the bell, then spies us and sits bolt upright in bed. "Well, what . . ." He throws into action a part of his rather colorful vocabulary. He evidently sees our intrusion in an unfavorable light at first, but soon relaxes a little and "supposes he must be late for breakfast". Seeing our stenographer taking down his remarks, he is puzzled for a moment, then breaks into a loud laugh, and cries out, "Oh! This is some more psychology. Well, go as far as you like. It must have been your bell I heard in my dream just now, when I thought I saw a lot of cannibals beating the tom-tom". Having now obtained sufficient data for quite a lengthy discussion, we retire to our staff room and deliberate upon these manifestations.

"The man perceives", we agree. "By the use of his eyes and ears he discovered facts, and interpreted them in the light of his previous experience. In knowing the facts, he also got adjusted to them and governed his actions by them. But notice--a curious thing--how his perception of the facts progressed by stages from the vague and erroneous to the correct and precise. Before he was fully awake, he mistook the bell for a tom-tom; then, more fully aroused, he knew the bell. Ourselves he first saw as mere wanton intruders, then as cheerful friends who wished him no ill; finally he saw us in our true character as investigators of his behavior."

Following our man through the day's work and recreation, we find a large share of his mental activity to consist in the perception of facts. We find that he makes use of the facts, adjusting himself to them and also shaping them to suit himself. His actions are governed by the facts perceived, at the same time that they are governed by his own desires. Ascertaining how the facts stand, he takes a hand and manipulates them. He is constantly coming to know {421} fresh facts, and constantly doing something new with them. His life is a voyage of discovery, and at the same time a career of invention.

Discovery and invention!--high-sounding words, still they are applicable to everyday life. The facts observed may not be absolutely new, but at least they have always to be verified afresh, since action needs always to take account of present reality. The invention may be very limited in scope, but seldom does an hour pass that does not call for doing something a little out of the ordinary, so as to escape from a fresh trap or pluck fruit from a newly discovered bough. All of our remaining chapters might, with a little forcing, be pigeonholed under these two great heads. Discovery takes its start with the child's instinctive exploratory activity, and invention with his manipulation, and these two tendencies, perhaps at bottom one, remain closely interlinked throughout.

Some DefinitionsPerception is the culmination of the process of discovery. Discovery usually requires exploration, a search for facts; and it requires attention, which amounts to finding the facts or getting them effectively presented; and perception then consists in knowing the presented facts.

When the facts are presented to the senses, we speak of "sense perception". If they are presented to the eye, we speak of visual perception; if to the ear, of auditory perception, etc. But when we speak of a fact as being "presented" to the eye or ear, we do not necessarily mean that it is directly and completely presented; it may only be indicated. We may have before the eyes simply a sign of some fact, but perceive the fact which is the meaning of the sign. We look out of

Comments (0)