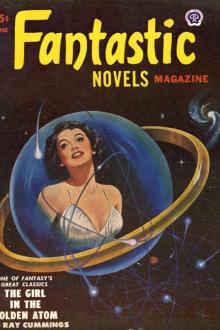

The Girl in the Golden Atom by Raymond King Cummings (online e book reader .txt) 📕

"You are quite right," said the Doctor; "but you did mention yourself that you hoped to provide proof."

The Chemist hesitated a moment, then made his decision. "I will tell you the rest," he said.

"After the destruction of the microscope, I was quite at a loss how to proceed. I thought about the problem for many weeks. Finally I decided to work along another altogether different line--a theory about which I am surprised you have not already questioned me."

He paused, but no one spoke.

"I am hardly ready with proof to-night," he resumed after a moment. "Will you all take dinner with me here at the club one week from to-night?" He read affirmation in the glance of each.

"Good. That's settled," he said, rising. "At seven, then."

"But what was the theory you expected us to question you about?" asked the Very Young Man.

Read free book «The Girl in the Golden Atom by Raymond King Cummings (online e book reader .txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Raymond King Cummings

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Girl in the Golden Atom by Raymond King Cummings (online e book reader .txt) 📕». Author - Raymond King Cummings

Aura saw it the same instant. She looked up helplessly to the Very Young Man above her; then she turned and ran down the gully.

The Very Young Man stood transfixed. It was a sheer drop of forty feet or more to the gully floor beneath him. There was seemingly nothing that he could do in those few terrible seconds, and yet with subconscious, instinctive reasoning, he did the one and only thing possible. A loose mass of the jagged, gold quartz hung over the gully wall. Frantically he tore at it—pried loose with feet and hands a bowlder that hung poised. As the lizard approached, the loosened rock slid forward, and dropped squarely upon the reptile's broad back.

It was a bowlder nearly as large as the Very Young Man himself, but the gigantic reptile shook it off, writhing and twisting for an instant, and hurling the smaller loose rocks about the floor of the gully with its struggles.

The Very Young Man cast about for another missile, but there were none at hand. Aura, at the confusion, had stopped about two hundred feet away.

"Run!" shouted the Very Young Man. "Hide somewhere! Run!"

The lizard, momentarily stunned, recovered swiftly. Again it started forward, seemingly now as alert as before. And then, without warning, in the air above his head the Very Young Man heard the rush of gigantic wings. A tremendous grey body swooped past him and into the gully—a bird larger in proportion than the lizard itself.... It was the little sparrow the Chemist had sent in from the outside world—maddened now by thirst and hunger, which to the reptile had been much more endurable.

The Very Young Man, shouting again to Aura to run, stood awestruck, watching the titanic struggle that was raging below him. The great lizard rose high on its forelegs to meet this enemy. Its tremendous jaws opened—and snapped closed; but the bird avoided them. Its huge claws gripped the reptile's back; its flapping wings spread the sixty foot width of the gully as it strove to raise its prey into the air. The roaring of these enormous wings was deafening; the wind from them as they came up tore past the Very Young Man in violent gusts; and as they went down, the suction of air almost swept him over the brink of the precipice. He flung himself prone, clinging desperately to hold his position.

The lizard threshed and squirmed. A swish of its enormous tail struck the gully wall and brought down an avalanche of loose, golden rock. But the giant bird held its grip; its bill—so large that the Very Young Man's body could easily have lain within it—pecked ferociously at the lizard's head.

It was a struggle to the death—an unequal struggle, though it raged for many minutes with an uncanny fury. At last, dragging its adversary to where the gully was wider, the bird flapped its wings with freedom of movement and laboriously rose into the air.

And a moment later the Very Young Man, looking upward, saw through the magic diminishing glass of distance, a little sparrow of his own world, with a tiny, helpless lizard struggling in its grasp.

"Aura! Don't cry, Aura! Gosh, I don't want you to cry—everything's all right now."

The Very Young Man sat awkwardly beside the frightened girl, who, overcome by the strain of what she had been through, was crying silently. It was strange to see Aura crying; she had always been such a Spartan, so different from any other girl he had ever known. It confused him.

"Don't cry, Aura," he repeated. He tried clumsily to soothe her. He wanted to thank her for what she had done in risking her life to find him. He wanted to tell her a thousand tender things that sprang into his heart as he sat there beside her. But when she raised her tear-stained face and smiled at him bravely, all he said was:

"Gosh, that was some fight, wasn't it? It was great of you to come down after me, Aura. Are they waiting for us up there?" And then when she nodded:

"We'd better hurry, Aura. How can we ever find them? We must have come miles from where they are."

She smiled at him quizzically through her tears.

"You forget, Jack, how small we are. They are waiting on the little ledge for us—and all this country—" She spread her arms toward the vast wilderness that surrounded them—"this is all only a very small part of that same ledge on which they are standing."

It was true; and the Very Young Man realized it at once.

Aura had both drugs with her. They took the one to increase their size, and without mishap or moving from where they were, rejoined those on the little ledge who were so anxiously awaiting them.

For half an hour the Very Young Man recounted his adventure, with praises of Aura that made the girl run to her sister to hide her confusion. Then once more the party started its short climb out of the valley of the scratch. In ten minutes they were all safely on the top—on the surface of the ring at last.

CHAPTER XL THE ADVENTURERS' RETURNThe Banker, lying huddled in his chair in the clubroom, awoke with a start. The ring lay at his feet—a shining, golden band gleaming brightly in the light as it lay upon the black silk handkerchief. The Banker shivered a little for the room was cold. Then he realized he had been asleep and looked at his watch. Three o'clock! They had been gone seven hours, and he had not taken the ring back to the Museum as they had told him to. He rose hastily to his feet; then as another thought struck him, he sat down again, staring at the ring.

The honk of an automobile horn in the street outside aroused him from his reverie. He got to his feet and mechanically began straightening up the room, packing up the several suit-cases. Then with obvious awe, and a caution that was almost ludicrous, he fixed the ring in its frame within the valise prepared for it. He lighted the little light in the valise, and, every moment or two, went back to look searchingly down at the ring inside.

When everything was packed the Banker left the room, returning in a moment with two of the club attendants. They carried the suit-cases outside, the Banker himself gingerly holding the bag containing the ring.

"A taxi," he ordered when they were at the door. Then he went to the desk, explaining that his friends had left earlier in the evening and that they had finished with the room.

To the taxi-driver he gave a number that was not the Museum address, but that of his own bachelor apartment on Park Avenue. It was still raining as he got into the taxi; he held the valise tightly on his lap, looking into it occasionally and gruffly ordering the chauffeur to drive slowly.

In the sumptuous living-room of his apartment he spread the handkerchief on the floor under the center electrolier and laid the ring upon it. Dismissing the astonished and only half-awake butler with a growl, he sat down in an easy-chair facing the ring, and in a few minutes more was again fast asleep.

In the morning when the maid entered he was still sleeping. Two hours later he rang for her, and gave tersely a variety of orders. These she and the butler obeyed with an air that plainly showed they thought their master had taken leave of his senses.

They brought him his breakfast and a bath-robe and slippers. And the butler carried in a mattress and a pair of blankets, laying them with a sigh on the hardwood floor in a corner of the room.

Then the Banker waved them away. He undressed, put on his bath-robe and slippers and sat down calmly to eat his breakfast. When he had finished he lighted a cigar and sat again in his easy-chair, staring at the ring, engrossed with his thoughts. Three days he would give them. Three days, to be sure they had made the trip successfully. Then he would take the ring to the Museum. And every Sunday he would visit it; until they came back—if they ever did.

The Banker's living-room with its usually perfect appointments was in thorough disorder. His meals were still being served him there by his dismayed servants. The mattress still lay in the corner; on it the rumpled blankets showed where he had been sleeping. For the hundredth time during his long vigil the Banker, still wearing his dressing-gown and slippers and needing a shave badly, put his face down close to the ring. His heart leaped into his throat; his breath came fast; for along the edge of the ring a tiny little line of figures was slowly moving.

He looked closer, careful lest his laboured breathing blow them away. He saw they were human forms—little upright figures, an eighth of an inch or less in height—moving slowly along one behind the other. He counted nine of them. Nine! he thought, with a shock of surprise. Why, only three had gone in! Then they had found Rogers, and were bringing him and others back with him!

Relief from the strain of many hours surged over the Banker. His eyes filled with tears; he dashed them away—and thought how ridiculous a feeling it was that possessed him. Then suddenly his head felt queer; he was afraid he was going to faint. He rose unsteadily to his feet, and threw himself full-length upon the mattress in the corner of the room. Then his senses faded. He seemed hardly to faint, but rather to drift off into an involuntary but pleasant slumber.

With returning consciousness the Banker heard in the room a confusion of many voices. He opened his eyes; the Doctor was sitting on the mattress beside him. The Banker smiled and parted his lips to speak, but the Doctor interrupted him.

"Well, old friend!" he cried heartily. "What happened to you? Here we are back all safely."

The Banker shook his friend's hand with emotion; then after a moment he sat up and looked about him. The room seemed full of people—strange looking figures, in extraordinary costumes, dirty and torn. The Very Young Man crowded forward.

"We got back, sir, didn't we?" he said.

The Banker saw he was holding a young girl by the hand—the most remarkable-looking girl, the Banker thought, that he had ever beheld. Her single garment, hanging short of her bare knees, was ragged and dirty; her jet black hair fell in tangled masses over her shoulders.

"This is Aura," said the Very Young Man. His voice was full of pride; his manner ingenuous as a child's.

Without a trace of embarrassment the girl smiled and with a pretty little bending of her head, held down her hand to the astonished Banker, who sat speechless upon his mattress.

Loto pushed forward. "That's mamita over there," he said, pointing. "Her name is Lylda; she's Aura's sister."

The Banker recovered his wits. "Well, and who are you, little man?" he asked with a smile.

"My name is Loto," the little boy answered earnestly. "That's my father." And he pointed across the room to where the Chemist was coming forward to join them.

CHAPTER XLI THE FIRST CHRISTMASChristmas Eve in a little village of Northern New York—a white Christmas, clear and cold. In the dark, blue-black of the sky the glittering stars were spread thick; the brilliant moon poured down its silver light over the whiteness of the sloping roof-tops, and upon the ghostly white, silently drooping trees. A heaviness hung in the frosty air—a stillness broken only by the tinkling of sleigh-bells or sometimes by the merry laughter of the passers-by.

At the outskirts of the village, a little back from the road, a farmhouse lay snuggled up between two huge apple-trees—an old-fashioned, rambling farmhouse with a steeply

Comments (0)