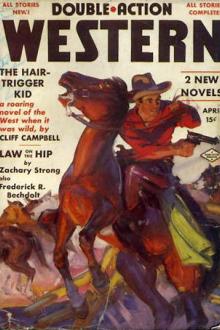

The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕

"The curtain ain't up," said the sheriff, "but I reckon that the stage is set and that they's gunna be an entrance pretty pronto."

"Here's somebody coming," said Georgia, gesturing toward the farther end of the street.

"Yeah," said the sheriff, "but he's comin' too slow to mean anything."

"Slow and earnest wins the race," said another.

They were growing impatient; like a crowd at a bullfight, when the entrance of the matador is delayed too long.

"We're wasting the day," said Milman to his family. "That's a long ride ahead of us."

"Don't go now," said Georgia. "I've got a tingle in my finger tips that says something is going to happen."

Other voices were rising, jesting, laughing, when some one called out something at the farther end of the veranda, and instantly there was a wave of silence that spread upon them all.

"What is it?" whispered Milman to the sheriff.

"Shut up!" said the sheriff. "They say th

Read free book «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕». Author - Max Brand

that’s all. There’s too darn many boys and fools along on this trip to

suit me. They got the place all cluttered up.”

“Aw—go to the dickens,” said the other suddenly. “You’ve got your

stomach soured and your head turned because some of the boys has been

fool enough to laugh at some of your bum jokes. I’m glad you’ve turned

your ankle. I wish you’d broke it, and your head along with it!”

“I’m going to wring your neck,” said the Kid, “when I get fixed of this.”

“Yeah?” demanded the other. “You’re gonna wring my neck, are you? Why,

you sucker, I could eat you in a salad and not know that you was there.

You make me sick!”

He turned on his heel with his final declaration and strode away.

He had used the strongest expression that the law allows. Swearing in its

most violent forms is as common as dust on the Western range, but there

is nothing in the entire, powerfu! range of the vocabulary which has the

meaning of the heartfelt statement: “You make me sick!” It takes the

heart out of the man addressed. It leaves him crumpled. It does not even

lead to a fight, usually. And the victim feels that he has been

criticized, not insulted.

“You make me sick!” said the puncher of the Dixon crowd, and then walked

away.

But the Kid, behind him, felt none of the usual qualms following this

speech. Instead, he could not help smiling. And that little touch of

triumph warmed his blood as thoroughly as an hour beside a steaming fire.

He went on in the same hobbling gait until the other had disappeared

among the shadows.

Then he stepped out freely and silently, and in another moment, found

himself between the last wagon and a heap of stuff which had been in part

unloaded from it.

Between the two objects he was comparatively safe.

And now that he was here, what was he to do?

He had not, in fact, the slightest idea. He had come down here with a

vague purpose of making trouble for the Dixonites; and he had even a sort

of dream-like consciousness of what that trouble might be.

In the first place, he might, however, work among the heaped pieces of

freight and come close enough to the fire to overhear some of the talk.

If he could learn the intimate plans of the enemy, that might give him a

clue on which to build his plans. So he went forward among the coils of

barbed wire, glimmering like silver where the highlights touched them.

And there were boxes of provisions, a pile of extra saddles and other

equipment. Through these he wriggled, until he had the groups around the

fire under his eyes.

Eight men were in view. Of these, five were obscure heaps in their

blankets, sleeping the sleep of the tired. Only one face could be seen.

The man lay on his back, his mouth open. Now and then he snored and

snorted in his sleep.

It was Peg Garret, well-known to the Kid, who recognized that face and

remembered the villainy of the owner of it. It was as though he were

suddenly put in touch with the evil of the entire crowd. Hand-picked for

cruelty and hard hearts, beyond a doubt.

Two others sat with a blanket between them, rolling dice, muttering,

throwing out and raking in money as they won and lost. For such a quiet

game the stakes were high, which told the Kid that these rascals had had

a fat advance payment for this work of theirs. To their right was Champ

Dixon, with his profile toward the Kid. As for the two gamblers, they

were Dolly Smith of gunfighting fame, a little, blond, smooth-faced boy

of nineteen with a reputation like dynamite; the other was the somber

face of Canuck Joe, who had a passion for fighting when the lights were

out. Bare hands were his favored weapons then, or a knife to fee! for the

throat of another in the dark.

Just then, into the light of the fire stepped a beetle-browed youth who

took out a red-and-yellow handkerchief and with it wiped his eyes. For

the thin dust cast up by the milling cattle was constantly blowing in the

air. Usually, it was hardly perceptible, but now and again a denser cloud

would roll in, red-stained above the fire. One of those clouds was

passing now, the newcomer snorted and grunted.

“Damn dirty work,” said he.

“What’s doin’, Jip?” asked Dixon.

“Aw, nothin’ much,” said Jip, whose voice the Kid recognized as that of

his recent companion in the shadow. “The cows is still workin’ up and

down the fences, but they ain’t gonna bust through. The boys is keepin’

them back, and the cows is gettin’ used to holdin’ off. They ain’t got no

nerve, these here beeves. They got no more nerve than old man Milman and

his crew. They’re tender, that’s what they are.”

“Yeah,” said Dixon. “They’re tender. I seen five thousand head down on

Chris Porter’s ranch in Arizona that would of beat in a stone wall with

their heads if they wanted that bad to get at water. They ain’t got no

brains, these cows. They’re stall-fed, what you might say.”

“Yeah, they’re stall-fed,” said the other. “Darn the dust. I’m gonna

taste it for a month.”

“No, you won’t, son. One shot of redeye will take the taste out of your

mouth.”

“Tell Bolony Joe to open up and pass around a little of the hot stuff,

will you, Champ?”

“Will I? I will not,” said Dixon. “I ain’t gonna have no bunch of drunks

on my hands.”

Jim made a cigarette.

“Larry has gone and got himself a sprained ankle,” said Jip.

“Hold on!” exclaimed Dixon. “How’d the fool do that?”

“Aw, he just goes down and gives himself a tumble by the creek, that’s

all.”

“Did he sprain it bad?” growled Dixon.

“He can’t walk, hardly. That’s how badly.”

“If he can walk at all, he can ride a lot.”

“Aw, maybe.”

“Where is he?”

“I dunno. I don’t care. He makes me sick,” observed Jip.

“What’s the matter with you and Larry? Larry’s all right,” broke in

little Dolly Smith.

“Is he? You have him then. I don’t want him,” said Jip. “He’s too blame

sour. Somebody’s gone and told Larry that he’s funny.”

“He is funny,” said Dolly. “I always get a good big laugh out of Larry.

The way he has of talking makes me laugh.”

“It don’t make me none,” replied Jip. “He makes me sick. That’s all.”

“What for does he make you sick?”

“He’s so blame sour. I wanted to help him to his blankets. He cursed me.

That’s what he done. He’s sour.”

“Give him some castor oil, Champ,” advised Dolly. “He’s very sick. Larry

makes him sick.”

“Yeah?” said Jip, raising his voice. “You don’t make me none too darn

well, yourself, as far as that goes.”

“Is that so?” said Dolly, jerking up his head like a bird on a branch

that sees trouble ahead. “Maybe I’m gonna make you feel a lot unweller,

before I get through.”

“You little sawed-off, pink-faced, pig-eyed runt,” said Jip, thoroughly

aroused. “You come out here and I’ll tell you something that your ma and

pa would like to hear!”

“You set where you are,” broke in Champ Dixon. “Jip, you back up.”

“I ain’t gonna take none of his backwash,” declared Jip.

“Who’s started all the fuss?” asked Champ. “You have. You come in here

and break up the party. How old are you, kid?”

“I said that Larry was a bust,” said Jip. “I told him to his own face.

‘You make me sick,’ I says to him. I told him off, is what I done.”

“If you said that, Larry would punch you in the eye,” observed little

Dolly Smith. “You wouldn’t never dare to say that to Larry. He’s got a

wallop like a mule. I seen him once in a Phoenix barroom when a couple of

elbows comes in to straighten out a fuss. They started something when

they got to Larry. And he done all the finishing. You keep your hands off

of Larry, kid, or you’re gonna lose about ten years’ growth one of these

days.”

“Thanks,” said Jip. “I tell you, Larry makes me sick. His idea of

kidding, it makes me sick too. ‘Who are you?’ says I, as he comes

crawlin’ along. ‘I’m the Kidl’ says he.”

Both Dolly and Canuck Joe put back their heads and laughed at this last

remark.

“He said he was the Kid,” Dolly Smith said, chuckling. “That’s pretty

good, Canuck, ain’t it?”

“That’s kind of funny,” said Canuck Joe, and laughed more loudly than

before.

“Shut up your faces,” said one of the sleepers, wakening.

“Yeah, pipe down,” advised Champ Dixon. “The boys has gotta get some

sleep, don’t they?”

“I’ll tel! you the trouble with you Dolly—” began Jip. Champ Dixon

raised one finger.

“Jip, you hear me? You back up.”

Jip glowered at his leader.

But that raised forefinger and that quiet voice had a meaning that was

very definite. He turned on his heel and retreated into the night,

declaring over his shoulder, that he was “sick of the whole business

anyway.”

Dolly Smith glared after him.

“Jip is only a fool kid,” said Dixon. “He’s all right.”

“Is he?” said Dolly coldly. “Where’s his call to come around here with

his back fur all standin’, I’d like to know? You hear that, Champ,” he

went on, “when Jip asked Larry who he was: ‘I’m the Kid,’ says he. That’s

pretty good, ain’t it?”

“Yeah, that’s rich,” Champ Dixon said, laughing. “The Kid is gonna come a

bust one of these days,” he added darkly.

“Sure he’s gonna come a bust,” remarked Dolly Smith. “But I don’t wanta

try the bustin’. Not till I’ve got my full growth. He’s too hot for the

kind of gloves that I wear.”

Canuck Joe thoughtfully spread out his own great hands and examined them

in the firelight as though they had a special and new meaning to him at

that moment.

“I dunno,” said he, doubtfully.

“You never seen him go,” said Dolly Smith. “I seen him go, though. Have

you ever seen that sweetheart work, Champ?”

“Yeah, I seen him work,” said Champ.

“He loves it, don’t he?”

“Yeah, he loves it, all right,” said Champ.

“He’s a ring-tai! little snake-eatin’ weasel, is what he is,” said Dolly

Smith fondly. “I seen him work one evening in Carson City. The dust he

raised, you couldn’t see your way for a week, in that town. I wonder how

Chip Graham is? I wonder what they’ll do with Chip?” he continued,

altering his voice.

“Shay’s gonna take care of that,” said Champ Dixon curtly. “There won’t

nothing happen to Chip. Shay ain’t that much a fool to let a good boy

like Chip down. He’ll stand by him.”

“He better, I’ll tell a man. If anything happens to Chip, there’s gonna

be a bust, I tell you. I’ll be right there at the busting, too. Too bad

you couldn’t get the Kid in on this here deal.”

“Well I tried to.”

“What did he say?”

“I’ll tell you something, Dolly. The Kid’s gone and

Comments (0)