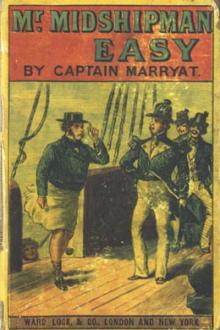

Mr. Midshipman Easy by Frederick Marryat (top 10 inspirational books txt) 📕

"You are correct, Doctor," replied Mr Easy, "and her head proves that she is a modest young woman, with strong religious feeling, kindness of disposition, and every other requisite."

"The head may prove it all for what I know, Mr Easy, but her conduct tells another tale."

"She is well fitted for the situation, ma'am," continued the Doctor.

"And if you please, ma'am," rejoined Sarah, "it was such a little one."

"Shall I try the baby, ma'am?" said the monthly nurse, who had listened in silence. "It is fretting so, poor thing, and has its dear little fist right down its throat."

Dr Middleton gave the signa

Read free book «Mr. Midshipman Easy by Frederick Marryat (top 10 inspirational books txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Frederick Marryat

- Performer: -

Read book online «Mr. Midshipman Easy by Frederick Marryat (top 10 inspirational books txt) 📕». Author - Frederick Marryat

“Without a crew or provisions-yachts don’t sail with a clean swept hold, or gentlemen without a spare shirt-we have nothing but two gallons of water and two pairs of pistols.”

“I have it,” said Jack-“we are two young gentlemen in our own boat who went out to Cozo with pistols to shoot sea-mews, were caught in a gale, and blown down to Sicily-that will excite interest.”

“That’s the best idea yet, as it will account for our having nothing in the boat. Well, then, at all events, we will get rid of the bodies; but suppose they are not dead-we cannot throw them overboard alive,-that will be murder.”

“Very true,” replied Jack, “then we must shoot them first, and toss them overboard afterwards.”

“Upon my soul, Easy, you are an odd fellow: however, go and examine the men, and we’ll decide that point by-and-bye: you had better keep your pistol ready cocked, for they may be shamming.”

“Devil a bit of sham here, anyhow,” replied Jack, pulling at the body of the padrone, “and as for this fellow you shot, you might put your fist into his chest. Now for the third,’ continued Jack, stepping over the strengthening piece-“he’s all among the baskets. I say, my cock, are you dead?” and Jack enforced his question with a kick in the ribs. The man groaned. “That’s unlucky, Gascoigne, but however, I’ll soon settle him,” said Jack, pointing his pistol.

“Stop, Jack,” cried Gascoigne, “it really will be murder.”

“No such thing, Ned; I’ll just blow his brains out, and then I’ll come aft and argue the point with you.”

“Now do oblige me by coming aft and arguing the point first. Do, Jack, I beg of you-I entreat you.”

“With all my heart,” replied Jack, resuming his seat by Gascoigne; “I assert, that in this instance killing’s no murder. You will observe, Ned, that by the laws of society, any one who attempts the life of another has forfeited his own; at the same time, as it is necessary that the fact should be clearly proved, and justice be duly administered, the parties are tried, convicted, and then are sentenced to the punishment.”

“I grant all that.”

“In this instance the attempt has been clearly proved; we are the witnesses, and are the judges and jury, and society in general, for the best of all possible reasons, because there is nobody else. These men’s lives, being therefore forfeited to society, belong to us; and it does not follow because they were not all killed in the attempt, that therefore they are not now to be brought out for punishment. And as there is no common hangman here, we, of course, must do this duty as well as every other. I have now clearly proved that I am justified in what I am about to do. But the argument does not stop there-self-preservation is the first law of nature, and if we do not get rid of this man, what is the consequence?-that we shall have to account for his being wounded, and then, instead of judges, we shall immediately be placed in the position of culprits, and have to defend ourselves without witnesses. We therefore risk our lives from a misplaced lenity towards a wretch unworthy to live.”

“Your last argument is strong, Easy, but I cannot consent to your doing what may occasion you uneasiness hereafter when you think of it.”

“Pooh! nonsense-I am a philosopher.”

“Of what school, Jack? Oh, I presume you are a disciple of Mesty’s. I do not mean to say that you are wrong, but still hear my proposition. Let us lower down the sail, and then I can leave the to assist you. We will clear the vessel of everything except the man who is still alive. At all events we may wait a little, and if at last there is no help for it, I will then agree with you to launch him overboard, even if he is not quite dead.”

“Agreed; even by your own making out, it will be no great sin. He is half dead already-I only do half the work of tossing him over, so it will be only quarter murder on my part, and he would have shown no quarter on his.” Here Jack left off arguing and punning, and went forward and lowered down the sail. “I’ve half a mind to take my doubloons back,” said Jack, as they launched over the body of the padrone, “but he may have them-I wonder whether they’ll ever turn up again.”

“Not in our time, Jack,” replied Gascoigne.

The other body, and all the basket lumber, &c., were then tossed over, and the boat was cleared of all but the man who was not yet dead.

“Now let’s examine the fellow, and see if he has any chance of recovery,” said Gascoigne.

The man lay on his side; Gascoigne turned him over and found that he was dead.

“Over with him, quick,” said Jack, “before he comes to life again.”

The body disappeared under the wave-they again hoisted the sail. Gascoigne took the helm, and our hero proceeded to draw water and wash away the stains of blood; he then cleared the boat of vine-leaves and rubbish, with which it was strewed, swept it clean fore and aft, and resumed his seat by his comrade.

“There,” said Jack, “now we’ve swept the decks, we may pipe to dinner. I wonder whether there is anything to eat in the locker.”

Jack opened it, and found some bread, garlic, sausages, a bottle of aquadente, and a jar of wine.

“So the padrone did keep his promise, after all.”

“Yes, and had you not tempted him with the sight of so much gold, might now have been alive.”

“To which I reply, that if you had not advised our going off in a speronare, he would now have been alive.”

“And if you had not fought a duel, I should not have given the advice.”

“And if the boatswain had not been obliged to come on board without his trousers at Gibraltar, I should not have fought a duel.”

“And if you had not joined the ship, the boatswain would have had his trousers on.”

“And if my father had not been a philosopher, I should not have gone to sea; so that it is all my father’s fault, and he has killed four men off the coast of Sicily without knowing it–cause and effect. After all. there’s nothing like argument; so, having settled that point, let us go to dinner.”

Having finished their meal, Jack went forward and observed the land ahead; they steered the same course for three or four hours.

“We must haul our wind more,” said Gascoigne; “it will not do to put into any small town; we have now to choose whether we shall land on the coast and sink the speronare, or land at some large town.”

“We must argue that point,” replied Jack.

“In the meantime, do you take the helm, for my arm is quite tired,” replied Gascoigne: “you can steer well enough: by-the-bye, I may as well look at my shoulder, for it is quite stiff.” Gascoigne pulled off his coat, and found his shirt bloody and sticking to the wound, which, as we before observed, was slight. He again took the helm, while Jack washed it clean, and then bathed it with aquadente.

“Now take the helm again,” said Gascoigne; “I’m on the sick list.”

“And as surgeon-I’m an idler,” replied Jack; “but what shall we do?” continued he; “abandon the speronare at night and sink her, or run in for a town?”

“We shall fall in with plenty of boats and vessels if we coast it up to Palermo, and they may overhaul us.”

“We shall fall in with plenty of people if we go on shore, and they will overhaul us.”

“Do you know, Jack, that I wish we were back and alongside of the Harpy, I’ve had cruising enough.”

“My cruises are so unfortunate,” replied Jack; “they are too full of adventure; but then I have never yet had a cruise on shore. Now, if we could only get to Palermo, we should be out of all our difficulties.”

“The breeze freshens, Jack,” replied Gascoigne; “and it begins to look very dirty to windward. I think we shall have a gale.”

“Pleasant-I know what it is to be short-handed in a gale; however, there’s one comfort, we shall not be blown off-shore this time.”

“No, but we may be wrecked on a lee shore. She cannot carry her whole sail, Easy; we must lower it down, and take in a reef; the sooner the better, for it will be dark in an hour. Go forward and lower it down, and then I’ll help you.”

Jack did so, but the sail went into the water, and he could not drag it in.

“Avast heaving,” said Gascoigne, “till I throw her up and take the wind out of it.”

This was done: they reefed the sail, but could not hoist it up: if Gascoigne left the helm to help Jack, the sail filled; if he went to the helm and took the wind out of the sail, Jack was not strong enough to hoist it. The wind increased rapidly, and the sea got up; the sun went down, and with the sail half hoisted, they could not keep to the wind, but were obliged to run right for the land. The speronare flew, rising on the crest of the waves with half her keel clear of the water: the moon was already up, and gave them light enough to perceive that they were not five miles from the coast, which was lined with foam.

“At all events they can’t accuse us of running away with the boat,” observed Jack; “for she’s running away with us.’

“Yes,” replied Gascoigne, dragging at the tiller with all his strength; “she has taken the bit between her teeth.”

“I wouldn’t care if I had a bit between mine,” replied Jack; “for I feel devilish hungry again. What do you say, Ned?”

“With all my heart,” replied Gascoigne; “but, do you know, Easy, it may be the last meal we ever make.”

“Then I vote it’s a good one-but why so, Ned?”

“In half an hour, or thereabouts, we shall be on shore.”

“Well, that’s where we want to go.”

“Yes, but the sea runs high, and the boat may be dashed to pieces on the rocks.”

“Then we shall be asked no questions about her or the men.”

“Very true, but a lee shore is no joke; we may be knocked to pieces as well as the boat-even swimming may not help us. If we could find a cove or sandy beach, we might perhaps manage to get on shore.”

“Well,” replied Jack, “I have not been long at sea, and, of course, cannot know much about these things. I have been blown off shore, but I never have been blown on. It may be as you say, but I do not see the great danger-let’s run her right up on the beach at once.”

“That’s what I shall try to do,” replied Gascoigne, who had been four years at sea, and knew very well what he was about.

Jack handed him a huge piece of bread and sausage.

“Thank ye, I cannot eat.”

“I can,” replied Jack, with his mouth full.

Jack ate while Gascoigne steered; and the rapidity with which the speronare rushed to the beach was almost frightful. She darted like an arrow from wave to wave, and appeared as if mocking their attempts as they curled their summits almost over her narrow stern. They were within a mile of the beach, when Jack, who had finished his supper, and was looking at the foam boiling

Comments (0)