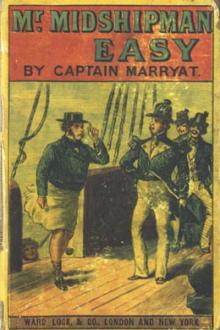

Mr. Midshipman Easy by Frederick Marryat (top 10 inspirational books txt) 📕

"You are correct, Doctor," replied Mr Easy, "and her head proves that she is a modest young woman, with strong religious feeling, kindness of disposition, and every other requisite."

"The head may prove it all for what I know, Mr Easy, but her conduct tells another tale."

"She is well fitted for the situation, ma'am," continued the Doctor.

"And if you please, ma'am," rejoined Sarah, "it was such a little one."

"Shall I try the baby, ma'am?" said the monthly nurse, who had listened in silence. "It is fretting so, poor thing, and has its dear little fist right down its throat."

Dr Middleton gave the signa

Read free book «Mr. Midshipman Easy by Frederick Marryat (top 10 inspirational books txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Frederick Marryat

- Performer: -

Read book online «Mr. Midshipman Easy by Frederick Marryat (top 10 inspirational books txt) 📕». Author - Frederick Marryat

“It’s very true,” observed the Governor, “that Mr Easy was of service to you when you were appointed; but allow me to observe, that for your ship, your prize-money, and for your windfall, you have been wholly indebted to your own gallantry, in both senses of the word; still Mr Easy is a fine generous fellow, and so is his son, I can tell you. By-the-bye, I had a long conversation with him the other day.”

“About himself?”

“Yes, all about himself. He appears to me to have come into the service without any particular motive, and will be just as likely to leave it in the same way. He appears to be very much in love with that Sicilian nobleman’s daughter. I find that he has written to her, and to her brother, since he has been here.”

“That he came into the service in search of what he never will find in this world, I know very well; and I presume that he has found that out-and that he will follow up the service is also very doubtful; but I do not wish that he should leave it yet, it is doing him great good,” replied Captain Wilson.’

“I agree with you there-I have great influence with him, and he shall stay yet awhile. He is heir to a very large fortune, is he not?”

“A clear eight thousand pounds a year, if not more.”

“If his father dies he must, of course, leave; a midshipman with eight thousand pounds a year would indeed be an anomaly.”

“That the service could not permit. It would be as injurious to himself as it would to others about him. At present, he has almost, indeed I may say quite, an unlimited command of money.”

“That’s bad, very bad. I wonder he behaves so well as he does.”

“And so do I: but he really is a very superior lad, with all his peculiarities, and a general favourite with those whose opinions and friendship are worth having.”

“Well, don’t curb him too tight-for really he does not require it. He goes very well in a snaffle.”

“Philosophy made Easy,” upon agrarian principles, the subject of some uneasiness to our hero-The first appearance, but not the last, of an important personage.

The conversation was here interrupted by a mail from England which they had been expecting. Captain Wilson retired with his letters; the Governor remained equally occupied; and our hero received the first letter ever written to him by his father. It ran “as follows:-

“MY DEAR SON, “I have many times taken up my pen with the intention of letting you know how things went on in this country. But as I can perceive around but one dark horizon of evil, I have as often laid it down again without venturing to make you unhappy with such bad intelligence.

“The account of your death, and also of your unexpectedly being yet spared to us, were duly received, and I trust, I mourned and rejoiced on each occasion with all the moderation characteristic of a philosopher. In the first instance I consoled myself with the reflection that the world you had left was in a state of slavery, and pressed down by the iron arm of despotism, and that to die was gain, not only in all the parson tells us, but also in our liberty; and, at the second intelligence, I moderated my joy for nearly about the same reasons, resolving, notwithstanding what Dr Middleton may say, to die as I have lived, a true philosopher.

“The more I reflect the more am I convinced that there is nothing required to make this world happy but equality, and the rights of man being duly observed-in short, that everything and everybody should be reduced to one level. Do we not observe that it is the law of nature-do not brooks run into rivers-rivers into seas-mountains crumble down upon the plains?-are not the seasons contented to equalise the parts of the earth? Why does the sun run round the ecliptic, instead of the equator, but to give an equal share of his heat to both sides of the world? Are we not all equally born in misery? does not death level us all aequo pede, as the poet hath? are we not all equally hungry, thirsty, and sleepy, and thus levelled by our natural wants? And such being the case, ought we not to have our equal share of good things in this world, to which we have undoubted equal right? Can any argument be more solid or more level than this, whatever nonsense Dr Middleton may talk?

“Yes, my son, if it were not that I still hope to see the sun of justice arise, and disperse the manifold dark clouds which obscure the land-if I did not still hope, in my time, to see an equal distribution of property-an Agrarian law passed by the House of Commons, in which all should benefit alike - I would not care how soon I left this vale of tears, created by tyranny and injustice. At present, the same system is carried on; the nation is taxed for the benefit of the few, and it groans under oppression and despotism; but I still do think that there is, if I may fortunately express myself, a bright star in the west; and signs of the times which comfort me. Already we have had a good deal of incendiarism about the country, and some of the highest aristocracy have pledged themselves to raise the people above themselves, and have advised sedition and conspiracy; have shown to the debased and unenlightened multitude that their force is physically irresistible, and recommended them to make use of it, promising that if they hold in power, they will only use that power to the abolition of our farce of a constitution, of a church, and of a king; and that if the nation is to be governed at all, it shall only be governed by the many. This is cheering. Hail, patriot lords! all hail! I am in hopes yet that the great work will be achieved, in spite of the laughs and sneers and shakes of the head, which my arguments still meet with from that obstinate fellow, Dr Middleton.

“Your mother is in a quiet way; she has given over reading and working, and even her knitting, as useless; and she now sits all day long at the chimney corner twiddling her thumbs, and waiting, as she says, for the millennium. Poor thing! she is very foolish with her ideas upon this matter, but as usual I let her have her own way in everything, copying the philosopher of old, who was tied to his Xantippe.

“I trust, my dear son, that your principles have strengthened with your years and fortified with your growth, and that, if necessary, you will sacrifice all to obtain what in my opinion will prove to be the real millennium. Make all the converts you can, and believe me to be, “Your affectionate father, and true guide, “Nicodemus Easy.”

Jack, who was alone, shook his head as he read this letter, and then laid it down with a pish! He did it involuntarily, and was surprised at himself when he found that he had so done. “I should like to argue the point,” thought Jack, in spite of himself; and then he threw the letter on the table, and went into Gascoigne’s room, displeased with his father and with himself. He asked Ned whether he had received any letters from England, and, it being near dinnertime, went back to dress. On his coming down into the receiving room with Gascoigne, the Governor said to them,–

“As you both speak Italian, you must take charge of a Sicilian officer, who has come here with letters of introduction to me, and who dines here to-day.”

Before dinner they were introduced to the party in question, a slight-made, well-looking young man, but still there was an expression in his countenance which was not agreeable. In compliance with the wishes of the Governor, Don Mathias, for so he was called, was placed between our two midshipmen, who immediately entered into conversation with him, being themselves anxious to make enquiries about their friends at Palermo. In the course of conversation, Jack enquired of him whether he was acquainted with Don Rebiera, to which the Sicilian answered in the affirmative, and they talked about the different members of the family. Don Mathias, towards the close of the dinner, enquired of Jack by what means he had become acquainted with Don Rebiera, and Jack, in reply, narrated how he and his friend Gascoigne had saved him from being murdered by two villains; after this reply the young officer appeared to be less inclined for conversation, but before the party broke up, requested to have the acquaintance of our two midshipmen. As soon as he was gone, Gascoigne observed in a reflective way, “I have seen that face before, but where I cannot exactly say; but you know, Jack, what a memory of people I have, and I have seen him before, I am sure.”

“I can’t recollect that ever I have,” replied our hero, “but I never knew anyone who could recollect in that way as you do.”

The conversation was then dropped between them, and Jack was for some time listening to the Governor and Captain Wilson, for the whole party were gone away, when Gascoigne, who had been in deep thought since he had made the observation to Jack, sprang up.

“I have him at last!” cried he.

“Have who?’ demanded Captain Wilson.

“That Sicilian officer-I could have sworn that I had seen him before.”

“That Don Mathias?”

“No, Sir Thomas! He is not Don Mathias! He is the very Don Silvio who was murdering Don Rebiera, when we came to his assistance and saved him.”

“I do believe you are right, Gascoigne.”

“I’m positive of it,” replied Gascoigne; “I never made a mistake in my life.”

“Bring me those letters, Easy,” said the Governor, “and let us see what they say of him. Here it is-Don Mathias de Alayeres. You may be mistaken, Gascoigne; it is a heavy charge you are making against this young man.”

“Well, Sir Thomas, if that is not Don Silvio, I’d forfeit my commission if I had it here in my hand. Besides, I observed the change in his countenance when we told him it was Easy and I who had come to Don Rebiera’s assistance; and did you observe after that, Easy, that he hardly said a word.”

“Very true,” replied Jack.

“Well, well, we must see to this,” observed the Governor; “if so, this letter of introduction must be a forgery.”

The party then retired to bed, and the next morning, while Easy was in Gascoigne’s room talking over their suspicions, letters from Palermo were brought up to him. They were in answer to those written by Jack on his arrival at Malta: a few lines from Don Rebiera, a small note from Agnes, and a voluminous detail from his friend Don Philip, who informed him of the good health of all parties, and of their goodwill towards him; of Agnes being as partial as ever; of his having spoken plainly, as he had promised Jack, to his father and mother relative to the mutual attachment; of their consent being given, and then withheld, because Father Thomaso, their confessor, would not listen to the union of Agnes with a heretic; but nevertheless telling Jack that this would be got over through the medium of his brother and himself, who were determined that their sister and he should not be made unhappy about such a trifle. But the latter part of the letter contained intelligence equally important, which was, that Don Silvio had again attempted the life of their father, and would

Comments (0)