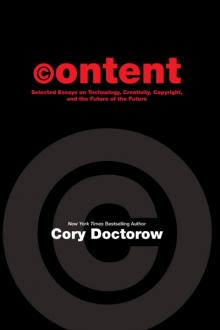

Content by Cory Doctorow (first e reader txt) 📕

And so it has been for the last 13 years. The companies that claim the ability to regulate humanity's Right to Know have been tireless in their endeavors to prevent the inevitable. The won most of the legislative battles in the U.S. and abroad, having purchased all the government money could buy. They even won most of the contests in court. They created digital rights management software schemes that behaved rather like computer viruses.

Indeed, they did about everything they could short of seriously examining the actual economics of the situation - it has never been proven to me that illegal downloads are more like shoplifted goods than viral marketing - or trying to come up with a business model that the market might embrace.

Had it been left to the stewardship of the usual suspects, there would scarcely be a word or a note online that you didn't have to pay to experience. There would be increasingly little free speech or any consequence, since free speech is not something anyone can o

Read free book «Content by Cory Doctorow (first e reader txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Cory Doctorow

- Performer: 1892391813

Read book online «Content by Cory Doctorow (first e reader txt) 📕». Author - Cory Doctorow

And here, finally, is the answer to the “Mostly harmless” problem. Ford’s editor can trim his verbiage to two words, but they need not stay there — Arthur, or any other user of the Guide as we know it today [fn: that is, in the era where we understand enough about technology to know the difference between a microprocessor and a hard-drive] can revert to Ford’s glorious and exhaustive version.

Think of it: a Guide without space restrictions and without editors, where any Vogon can publish to his heart’s content.

Lovely.

$$$$

Warhol is Turning in His Grave

(Originally published in The Guardian, November 13, 2007)

The excellent little programmer book for the National Portrait Gallery’s current show POPARTPORTRAITS has a lot to say about the pictures hung on the walls, about the diverse source material the artists drew from in producing their provocative works. They cut up magazines, copied comic books, drew in trademarked cartoon characters like Minnie Mouse, reproduced covers from Time magazine, made ironic use of the cartoon figure of Charles Atlas, painted over an iconic photo of James Dean or Elvis Presley — and that’s just in the first room of seven.

The programmer book describes the aesthetic experience of seeing these repositioned icons of culture high and low, the art created by the celebrated artists Poons, Rauschenberg, Warhol, et al by nicking the work of others, without permission, and remaking it to make statements and evoke emotions never countenanced by the original creators.

However, the book does not say a word about copyright. Can you blame it? A treatise on the way that copyright and trademark were — had to be — trammeled to make these works could fill volumes. Reading the programmer book, you have to assume that the curators’ only message about copyright is that where free expression is concerned, the rights of the creators of the original source material appropriated by the pop school take a back seat.

There is, however, another message about copyright in the National Portrait Gallery: it’s implicit in the “No Photography” signs prominently placed throughout the halls, including one right by the entrance of the POPARTPORTRAITS exhibition. This isn’t intended to protect the works from the depredations of camera-flashes (it would read NO FLASH PHOTOGRAPHY if this were so). No, the ban on pictures is in place to safeguard the copyright in the works hung on the walls — a fact that every gallery staffer I spoke to instantly affirmed when I asked about the policy.

Indeed, it seems that every square centimeter of the Portrait Gallery is under some form of copyright. I wasn’t even allowed to photograph the NO PHOTOGRAPHS sign. A museum staffer explained that she’d been told that the typography and layout of the NO PHOTOGRAPHS legend was, itself, copyrighted. If this is true, then presumably, the same rules would prevent anyone from taking any pictures in any public place — unless you could somehow contrive to get a shot of Leicester Square without any writing, logos, architectural facades, or images in it. I doubt Warhol could have done it.

What’s the message of the show, then? Is it a celebration of remix culture, reveling in the endless possibilities opened up by appropriating and re-using without permission?

Or is it the epitaph on the tombstone of the sweet days before the UN’s chartering of the World Intellectual Property Organization and the ensuing mania for turning everything that can be sensed and recorded into someone’s property?

Does this show — paid for with public money, with some works that are themselves owned by public institutions — seek to inspire us to become 21st century pops, armed with cameraphones, websites and mixers, or is it supposed to inform us that our chance has passed, and we’d best settle for a life as information serfs, who can’t even make free use of what our eyes see, our ears hear, of the streets we walk upon?

Perhaps, just perhaps, it’s actually a Dadaist show masquerading as a pop art show! Perhaps the point is to titillate us with the delicious irony of celebrating copyright infringement while simultaneously taking the view that even the NO PHOTOGRAPHY sign is a form of property, not to be reproduced without the permission that can never be had.

$$$$

The Future of Ignoring Things

(Originally published on InformationWeek’s Internet Evolution, October 3, 2007)

For decades, computers have been helping us to remember, but now it’s time for them to help us to ignore.

Take email: Endless engineer-hours are poured into stopping spam, but virtually no attention is paid to our interaction with our non-spam messages. Our mailer may strive to learn from our ratings what is and is not spam, but it expends practically no effort on figuring out which of the non-spam emails are important and which ones can be safely ignored, dropped into archival folders, or deleted unread.

For example, I’m forever getting cc’d on busy threads by well-meaning colleagues who want to loop me in on some discussion in which I have little interest. Maybe the initial group invitation to a dinner (that I’ll be out of town for) was something I needed to see, but now that I’ve declined, I really don’t need to read the 300+ messages that follow debating the best place to eat.

I could write a mail-rule to ignore the thread, of course. But mail-rule editors are clunky, and once your rule-list grows very long, it becomes increasingly unmanageable. Mail-rules are where bookmarks were before the bookmark site del.icio.us showed up — built for people who might want to ensure that messages from the boss show up in red, but not intended to be used as a gigantic storehouse of a million filters, a crude means for telling the computers what we don’t want to see.

Rael Dornfest, the former chairman of the O’Reilly Emerging Tech conference and founder of the startup IWantSandy, once proposed an “ignore thread” feature for mailers: Flag a thread as uninteresting, and your mailer will start to hide messages with that subject-line or thread-ID for a week, unless those messages contain your name. The problem is that threads mutate. Last week’s dinner plans become this week’s discussion of next year’s group holiday. If the thread is still going after a week, the messages flow back into your inbox — and a single click takes you back through all the messages you missed.

We need a million measures like this, adaptive systems that create a gray zone between “delete on sight” and “show this to me right away.”

RSS readers are a great way to keep up with the torrent of new items posted on high-turnover sites like Digg, but they’re even better at keeping up with sites that are sporadic, like your friend’s brilliant journal that she only updates twice a year. But RSS readers don’t distinguish between the rare and miraculous appearance of a new item in an occasional journal and the latest click-fodder from Slashdot. They don’t even sort your RSS feeds according to the sites that you click-through the most.

There was a time when I could read the whole of Usenet — not just because I was a student looking for an excuse to avoid my assignments, but because Usenet was once tractable, readable by a single determined person. Today, I can’t even keep up with a single high-traffic message-board. I can’t read all my email. I can’t read every item posted to every site I like. I certainly can’t plough through the entire edit-history of every Wikipedia entry I read. I’ve come to grips with this — with acquiring information on a probabilistic basis, instead of the old, deterministic, cover-to-cover approach I learned in the offline world.

It’s as though there’s a cognitive style built into TCP/IP. Just as the network only does best-effort delivery of packets, not worrying so much about the bits that fall on the floor, TCP/IP users also do best-effort sweeps of the Internet, focusing on learning from the good stuff they find, rather than lamenting the stuff they don’t have time to see.

The network won’t ever become more tractable. There will never be fewer things vying for our online attention. The only answer is better ways and new technology to ignore stuff — a field that’s just being born, with plenty of room to grow.

$$$$

Facebook’s Faceplant

(Originally published as “How Your Creepy Ex-Co-Workers Will Kill Facebook,” in InformationWeek, November 26, 2007)

Facebook’s “platform” strategy has sparked much online debate and controversy. No one wants to see a return to the miserable days of walled gardens, when you couldn’t send a message to an AOL subscriber unless you, too, were a subscriber, and when the only services that made it were the ones that AOL management approved. Those of us on the “real” Internet regarded AOL with a species of superstitious dread, a hive of clueless noobs waiting to swamp our beloved Usenet with dumb flamewars (we fiercely guarded our erudite flamewars as being of a palpably superior grade), the wellspring of an

Facebook is no paragon of virtue. It bears the hallmarks of the kind of pump-and-dump service that sees us as sticky, monetizable eyeballs in need of pimping. The clue is in the steady stream of emails you get from Facebook: “So-and-so has sent you a message.” Yeah, what is it? Facebook isn’t telling — you have to visit Facebook to find out, generate a banner impression, and read and write your messages using the halt-and-lame Facebook interface, which lags even end-of-lifed email clients like Eudora for composing, reading, filtering, archiving and searching. Emails from Facebook aren’t helpful messages, they’re eyeball bait, intended to send you off to the Facebook site, only to discover that Fred wrote “Hi again!” on your “wall.” Like other “social” apps (cough eVite cough), Facebook has all the social graces of a nose-picking, hyperactive six-year-old, standing at the threshold of your attention and chanting, “I know something, I know something, I know something, won’t tell you what it is!”

If there was any doubt about Facebook’s lack of qualification to displace the Internet with a benevolent dictatorship/walled garden, it was removed when Facebook unveiled its new advertising campaign. Now, Facebook will allow its advertisers use the profile pictures of Facebook users to advertise their products, without permission or compensation. Even if you’re the kind of person who likes the sound of a “benevolent dictatorship,” this clearly isn’t one.

Many of my colleagues wonder if Facebook can be redeemed by opening up the platform, letting anyone write any app for the service, easily exporting and importing their data, and so on (this is the kind of thing Google is doing with its OpenSocial Alliance). Perhaps if Facebook takes on some of the characteristics that made the Web work — openness, decentralization, standardization — it will become like the Web itself, but with the added pixie dust of “social,” the indefinable characteristic that makes Facebook into pure crack for a significant proportion of Internet users.

The debate about redeeming Facebook starts from the assumption that Facebook is snowballing toward critical mass, the point at which it begins to define “the Internet” for a large slice of the world’s netizens, growing steadily every day. But I think that this is far from a sure thing. Sure, networks generally follow Metcalfe’s Law: “the value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of users of the system.” This law is best understood through the analogy of the fax machine: a world with one fax machine has no use for faxes, but every time you add a fax, you square the number of possible send/receive combinations (Alice can fax Bob or Carol or Don; Bob

Comments (0)