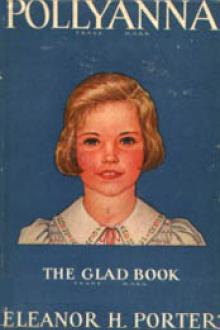

Pollyanna by Eleanor Hodgman Porter (most motivational books .TXT) 📕

"The little girl will be all ready to start by the time you get this letter; and if you can take her, we would appreciate it very much if you would write that she might come at once, as there is a man and his wife here who are going East very soon, and they would take her with them to Boston, and put her on the Beldingsville train. Of course you would be notified what day and train to expect Pollyanna on. Pollyanna

"Hoping to hear favorably from you soon, I remain, "Respectfully yours, "Jeremiah O. White."

With a frown Miss Polly folded the letter and tucked it into its envelope. She had answered it the day before, and she had said she would take the child, of course. She HOPED she knew her duty well enough for that!--disagreeable as the task would be.

As she sat now, with the letter in her hands, her thoughts went back to her sister, Jennie, who had been this child's mother, and to the time when Jennie, as

Read free book «Pollyanna by Eleanor Hodgman Porter (most motivational books .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Eleanor Hodgman Porter

- Performer: -

Read book online «Pollyanna by Eleanor Hodgman Porter (most motivational books .TXT) 📕». Author - Eleanor Hodgman Porter

“Nothing, dear. I was changing the position of this prism,” said Aunt Polly, whose whole face now was aflame.

CHAPTER XXVIII. THE GAME AND ITS PLAYERS

It was not long after John Pendleton’s second visit that Milly Snow called one afternoon. Milly Snow had never before been to the Harrington homestead. She blushed and looked very embarrassed when Miss Polly entered the room.

“I—I came to inquire for the little girl,” she stammered.

“You are very kind. She is about the same. How is your mother?” rejoined Miss Polly, wearily.

“That is what I came to tell you—that is, to ask you to tell Miss Pollyanna,” hurried on the girl, breathlessly and incoherently. “We think it’s—so awful—so perfectly awful that the little thing can’t ever walk again; and after all she’s done for us, too—for mother, you know, teaching her to play the game, and all that. And when we heard how now she couldn’t play it herself—poor little dear! I’m sure I don’t see how she CAN, either, in her condition!—but when we remembered all the things she’d said to us, we thought if she could only know what she HAD done for us, that it would HELP, you know, in her own case, about the game, because she could be glad—that is, a little glad—” Milly stopped helplessly, and seemed to be waiting for Miss Polly to speak.

Miss Polly had sat politely listening, but with a puzzled questioning in her eyes. Only about half of what had been said, had she understood. She was thinking now that she always had known that Milly Snow was “queer,” but she had not supposed she was crazy. In no other way, however, could she account for this incoherent, illogical, unmeaning rush of words. When the pause came she filled it with a quiet:

“I don’t think I quite understand, Milly. Just what is it that you want me to tell my niece?”

“Yes, that’s it; I want you to tell her,” answered the girl, feverishly. “Make her see what she’s done for us. Of course she’s SEEN some things, because she’s been there, and she’s known mother is different; but I want her to know HOW different she is—and me, too. I’m different. I’ve been trying to play it—the game—a little.”

Miss Polly frowned. She would have asked what Milly meant by this “game,” but there was no opportunity. Milly was rushing on again with nervous volubility.

“You know nothing was ever right before—for mother. She was always wanting ‘em different. And, really, I don’t know as one could blame her much—under the circumstances. But now she lets me keep the shades up, and she takes interest in things—how she looks, and her nightdress, and all that. And she’s actually begun to knit little things—reins and baby blankets for fairs and hospitals. And she’s so interested, and so GLAD to think she can do it!—and that was all Miss Pollyanna’s doings, you know, ‘cause she told mother she could be glad she’d got her hands and arms, anyway; and that made mother wonder right away why she didn’t DO something with her hands and arms. And so she began to do something—to knit, you know. And you can’t think what a different room it is now, what with the red and blue and yellow worsteds, and the prisms in the window that SHE gave her—why, it actually makes you feel BETTER just to go in there now; and before I used to dread it awfully, it was so dark and gloomy, and mother was so—so unhappy, you know.

“And so we want you to please tell Miss Pollyanna that we understand it’s all because of her. And please say we’re so glad we know her, that we thought, maybe if she knew it, it would make her a little glad that she knew us. And—and that’s all,” sighed Milly, rising hurriedly to her feet. “You’ll tell her?”

“Why, of course,” murmured Miss Polly, wondering just how much of this remarkable discourse she could remember to tell.

These visits of John Pendleton and Milly Snow were only the first of many; and always there were the messages—the messages which were in some ways so curious that they caused Miss Polly more and more to puzzle over them.

One day there was the little Widow Benton. Miss Polly knew her well, though they had never called upon each other. By reputation she knew her as the saddest little woman in town—one who was always in black. To-day, however, Mrs. Benton wore a knot of pale blue at the throat, though there were tears in her eyes. She spoke of her grief and horror at the accident; then she asked diffidently if she might see Pollyanna.

Miss Polly shook her head.

“I am sorry, but she sees no one yet. A little later—perhaps.”

Mrs. Benton wiped her eyes, rose, and turned to go. But after she had almost reached the hall door she came back hurriedly.

“Miss Harrington, perhaps, you’d give her—a message,” she stammered.

“Certainly, Mrs. Benton; I shall be very glad to.”

Still the little woman hesitated; then she spoke.

“Will you tell her, please, that—that I’ve put on THIS,” she said, just touching the blue bow at her throat. Then, at Miss Polly’s ill-concealed look of surprise, she added: “The little girl has been trying for so long to make me wear—some color, that I thought she’d be—glad to know I’d begun. She said that Freddy would be so glad to see it, if I would. You know Freddy’s ALL I have now. The others have all—” Mrs. Benton shook her head and turned away. “If you’ll just tell Pollyanna—SHE’LL understand.” And the door closed after her.

A little later, that same day, there was the other widow—at least, she wore widow’s garments. Miss Polly did not know her at all. She wondered vaguely how Pollyanna could have known her. The lady gave her name as “Mrs. Tarbell.”

“I’m a stranger to you, of course,” she began at once. “But I’m not a stranger to your little niece, Pollyanna. I’ve been at the hotel all summer, and every day I’ve had to take long walks for my health. It was on these walks that I’ve met your niece—she’s such a dear little girl! I wish I could make you understand what she’s been to me. I was very sad when I came up here; and her bright face and cheery ways reminded me of—my own little girl that I lost years ago. I was so shocked to hear of the accident; and then when I learned that the poor child would never walk again, and that she was so unhappy because she couldn’t be glad any longer—the dear child!—I just had to come to you.”

“You are very kind,” murmured Miss Polly.

“But it is you who are to be kind,” demurred the other. “I—I want you to give her a message from me. Will you?”

“Certainly.”

“Will you just tell her, then, that Mrs. Tarbell is glad now. Yes, I know it sounds odd, and you don’t understand. But—if you’ll pardon me I’d rather not explain.” Sad lines came to the lady’s mouth, and the smile left her eyes. “Your niece will know just what I mean; and I felt that I must tell—her. Thank you; and pardon me, please, for any seeming rudeness in my call,” she begged, as she took her leave.

Thoroughly mystified now, Miss Polly hurried up-stairs to Pollyanna’s room.

“Pollyanna, do you know a Mrs. Tarbell?

“Oh, yes. I love Mrs. Tarbell. She’s sick, and awfully sad; and she’s at the hotel, and takes long walks. We go together. I mean—we used to.” Pollyanna’s voice broke, and two big tears rolled down her cheeks.

Miss Polly cleared her throat hurriedly.

“We’ll, she’s just been here, dear. She left a message for you—but she wouldn’t tell me what it meant. She said to tell you that Mrs. Tarbell is glad now.”

Pollyanna clapped her hands softly.

“Did she say that—really? Oh, I’m so glad!

“But, Pollyanna, what did she mean?”

“Why, it’s the game, and—” Pollyanna stopped short, her fingers to her lips.

“What game?”

“N-nothing much, Aunt Polly; that is—I can’t tell it unless I tell other things that—that I’m not to speak of.”

It was on Miss Polly’s tongue to question her niece further; but the obvious distress on the little girl’s face stayed the words before they were uttered.

Not long after Mrs. Tarbell’s visit, the climax came. It came in the shape of a call from a certain young woman with unnaturally pink cheeks and abnormally yellow hair; a young woman who wore high heels and cheap jewelry; a young woman whom Miss Polly knew very well by reputation—but whom she was angrily amazed to meet beneath the roof of the Harrington homestead.

Miss Polly did not offer her hand. She drew back, indeed, as she entered the room.

The woman rose at once. Her eyes were very red, as if she had been crying. Half defiantly she asked if she might, for a moment, see the little girl, Pollyanna.

Miss Polly said no. She began to say it very sternly; but something in the woman’s pleading eyes made her add the civil explanation that no one was allowed yet to see Pollyanna.

The woman hesitated; then a little brusquely she spoke. Her chin was still at a slightly defiant tilt.

“My name is Mrs. Payson—Mrs. Tom Payson. I presume you’ve heard of me—most of the good people in the town have—and maybe some of the things you’ve heard ain’t true. But never mind that. It’s about the little girl I came. I heard about the accident, and—and it broke me all up. Last week I heard how she couldn’t ever walk again, and—and I wished I could give up my two uselessly well legs for hers. She’d do more good trotting around on ‘em one hour than I could in a hundred years. But never mind that. Legs ain’t always given to the one who can make the best use of ‘em, I notice.”

She paused, and cleared her throat; but when she resumed her voice was still husky.

“Maybe you don’t know it, but I’ve seen a good deal of that little girl of yours. We live on the Pendleton Hill road, and she used to go by often—only she didn’t always GO BY. She came in and played with the kids and talked to me—and my man, when he was home. She seemed to like it, and to like us. She didn’t know, I suspect, that her kind of folks don’t generally call on my kind. Maybe if they DID call more, Miss Harrington, there wouldn’t be so many—of my kind,” she added, with sudden bitterness.

“Be that as it may, she came; and she didn’t do herself no harm, and she did do us good—a lot o’ good. How much she won’t know—nor can’t know, I hope; ‘cause if she did, she’d know other things—that I don’t want her to know.

“But it’s just this. It’s been hard times with us this year, in more ways than one. We’ve been blue and discouraged—my man and me, and ready for—‘most anything. We was reckoning on getting a divorce about now, and letting the kids well, we didn’t know what we would do with the kids, Then came the accident, and what we heard about the little girl’s never walking again. And we got to thinking how she used to come

Comments (0)