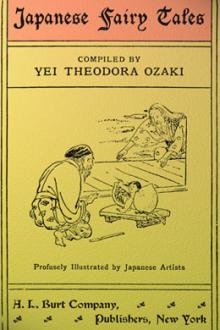

Japanese Fairy Tales by Yei Theodora Ozaki (best books to read now .TXT) 📕

Y. T. O.

Tokio, 1908.

CONTENTS.

MY LORD BAG OF RICE

THE TONGUE-CUT SPARROW

THE STORY OF URASHIMA TARO, THE FISHER LAD

THE FARMER AND THE BADGER

THE "shinansha," OR THE SOUTH POINTING CARRIAGE

THE ADVENTURES OF KINTARO, THE GOLDEN BOY

THE STORY OF PRINCESS HASE

THE STORY OF THE MAN WHO DID NOT WISH TO DIE

THE BAMBOO-CUTTER AND THE MOON-CHILD

THE MIRROR OF MATSUYAMA

THE GOBLIN OF ADACHIGAHARA

THE SAGACIOUS MONKEY AND THE BOAR

THE HAPPY HUNTER AND THE SKILLFUL FISHER

THE STORY OF THE OLD MAN WHO MADE WITHERED

Read free book «Japanese Fairy Tales by Yei Theodora Ozaki (best books to read now .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Yei Theodora Ozaki

- Performer: 1592249191

Read book online «Japanese Fairy Tales by Yei Theodora Ozaki (best books to read now .TXT) 📕». Author - Yei Theodora Ozaki

One evening the man came home in a very bad temper and told his wife to send for the butcher the next morning.

The wife was very bewildered and asked her husband:

“Why do you wish me to send for the butcher?”

“It’s no use taking that monkey round any longer, he’s too old and forgets his tricks. I beat him with my stick all I know how, but he won’t dance properly. I must now sell him to the butcher and make what money out of him I can. There is nothing else to be done.”

The woman felt very sorry for the poor little animal, and pleaded for her husband to spare the monkey, but her pleading was all in vain, the man was determined to sell him to the butcher.

Now the monkey was in the next room and overheard ever word of the conversation. He soon understood that he was to be killed, and he said to himself:

“Barbarous, indeed, is my master! Here I have served him faithfully for years, and instead of allowing me to end my days comfortably and in peace, he is going to let me be cut up by the butcher, and my poor body is to be roasted and stewed and eaten? Woe is me! What am I to do. Ah! a bright thought has struck me! There is, I know, a wild bear living in the forest near by. I have often heard tell of his wisdom. Perhaps if I go to him and tell him the strait I am in he will give me his counsel. I will go and try.”

There was no time to lose. The monkey slipped out of the house and ran as quickly as he could to the forest to find the boar. The boar was at home, and the monkey began his tale of woe at once.

“Good Mr. Boar, I have heard of your excellent wisdom. I am in great trouble, you alone can help me. I have grown old in the service of my master, and because I cannot dance properly now he intends to sell me to the butcher. What do you advise me to do? I know how clever you are!”

The boar was pleased at the flattery and determined to help the monkey. He thought for a little while and then said:

“Hasn’t your master a baby?”

“Oh, yes,” said the monkey, “he has one infant son.”

“Doesn’t it lie by the door in the morning when your mistress begins the work of the day? Well, I will come round early and when I see my opportunity I will seize the child and run off with it.”

“What then?” said the monkey.

“Why the mother will be in a tremendous scare, and before your master and mistress know what to do, you must run after me and rescue the child and take it home safely to its parents, and you will see that when the butcher comes they won’t have the heart to sell you.”

The monkey thanked the boar many times and then went home. He did not sleep much that night, as you may imagine, for thinking of the morrow. His life depended on whether the boar’s plan succeeded or not. He was the first up, waiting anxiously for what was to happen. It seemed to him a very long time before his master’s wife began to move about and open the shutters to let in the light of day. Then all happened as the boar had planned. The mother placed her child near the porch as usual while she tidied up the house and got her breakfast ready.

The child was crooning happily in the morning sunlight, dabbing on the mats at the play of light and shadow. Suddenly there was a noise in the porch and a loud cry from the child. The mother ran out from the kitchen to the spot, only just in time to see the boar disappearing through the gate with her child in its clutch. She flung out her hands with a loud cry of despair and rushed into the inner room where her husband was still sleeping soundly.

He sat up slowly and rubbed his eyes, and crossly demanded what his wife was making all that noise about. By the time that the man was alive to what had happened, and they both got outside the gate, the boar had got well away, but they saw the monkey running after the thief as hard as his legs would carry him.

Both the man and wife were moved to admiration at the plucky conduct of the sagacious monkey, and their gratitude knew no bounds when the faithful monkey brought the child safely back to their arms.

“There!” said the wife. “This is the animal you want to kill—if the monkey hadn’t been here we should have lost our child forever.”

“You are right, wife, for once,” said the man as he carried the child into the house. “You may send the butcher back when he comes, and now give us all a good breakfast and the monkey too.”

When the butcher arrived he was sent away with an order for some boar’s meat for the evening dinner, and the monkey was petted and lived the rest of his days in peace, nor did his master ever strike him again.

THE HAPPY HUNTER AND THE SKILLFUL FISHER.

Long, long ago Japan was governed by Hohodemi, the fourth Mikoto (or Augustness) in descent from the illustrious Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess. He was not only as handsome as his ancestress was beautiful, but he was also very strong and brave, and was famous for being the greatest hunter in the land. Because of his matchless skill as a hunter, he was called “Yama-sachi-hiko” or “The Happy Hunter of the Mountains.”

His elder brother was a very skillful fisher, and as he far surpassed all rivals in fishing, he was named “Unii-sachi-hiko” or the “Skillful Fisher of the Sea.” The brothers thus led happy lives, thoroughly enjoying their respective occupations, and the days passed quickly and pleasantly while each pursued his own way, the one hunting and the other fishing.

One day the Happy Hunter came to his brother, the Skillful Fisher, and said:

“Well, my brother, I see you go to the sea every day with your fishing rod in your hand, and when you return you come laden with fish. And as for me, it is my pleasure to take my bow and arrow and to hunt the wild animals up the mountains and down in the valleys. For a long time we have each followed our favorite occupation, so that now we must both be tired, you of your fishing and I of my hunting. Would it not be wise for us to make a change? Will you try hunting in the mountains and I will go and fish in the sea?”

The Skillful Fisher listened in silence to his brother, and for a moment was thoughtful, but at last he answered:

“O yes, why not? Your idea is not a bad one at all. Give me your bow and arrow and I will set out at once for the mountains and hunt for game.”

So the matter was settled by this talk, and the two brothers each started out to try the other’s occupation, little dreaming of all that would happen. It was very unwise of them, for the Happy Hunter knew nothing of fishing, and the Skillful Fisher, who was bad tempered, knew as much about hunting.

The Happy Hunter took his brother’s much-prized fishing hook and rod and went down to the seashore and sat down on the rocks. He baited his hook and then threw it into the sea clumsily. He sat and gazed at the little float bobbing up and down in the water, and longed for a good fish to come and be caught. Every time the buoy moved a little he pulled up his rod, but there was never a fish at the end of it, only the hook and the bait. If he had known how to fish properly, he would have been able to catch plenty of fish, but although he was the greatest hunter in the land he could not help being the most bungling fisher.

The whole day passed in this way, while he sat on the rocks holding the fishing rod and waiting in vain for his luck to turn. At last the day began to darken, and the evening came; still he had caught not a single fish. Drawing up his line for the last time before going home, he found that he had lost his hook without even knowing when he had dropped it.

He now began to feel extremely anxious, for he knew that his brother would be angry at his having lost his hook, for, it being his only one, he valued it above all other things. The Happy Hunter now set to work to look among the rocks and on the sand for the lost hook, and while he was searching to and fro, his brother, the Skillful Fisher, arrived on the scene. He had failed to find any game while hunting that day, and was not only in a bad temper, but looked fearfully cross. When he saw the Happy Hunter searching about on the shore he knew that something must have gone wrong, so he said at once:

“What are you doing, my brother?”

The Happy Hunter went forward timidly, for he feared his brother’s anger, and said:

“Oh, my brother, I have indeed done badly.”

“What is the matter?—what have you done?” asked the elder brother impatiently.

“I have lost your precious fishing hook—”

While he was still speaking his brother stopped him, and cried out fiercely:

“Lost my hook! It is just what I expected. For this reason, when you first proposed your plan of changing over our occupations I was really against it, but you seemed to wish it so much that I gave in and allowed you to do as you wished. The mistake of our trying unfamiliar tasks is soon seen! And you have done badly. I will not return you your bow and arrow till you have found my hook. Look to it that you find it and return it to me quickly.”

The Happy Hunter felt that he was to blame for all that had come to pass, and bore his brother’s scornful scolding with humility and patience. He hunted everywhere for the hook most diligently, but it was nowhere to be found. He was at last obliged to give up all hope of finding it. He then went home, and in desperation broke his beloved sword into pieces and made five hundred hooks out of it.

He took these to his angry brother and offered them to him, asking his forgiveness, and begging him to accept them in the place of the one he had lost for him. It was useless; his brother would not listen to him, much less grant his request.

The Happy Hunter then made another five hundred hooks, and again took them to his brother, beseeching him to pardon him.

“Though you make a million hooks,” said the Skillful Fisher, shaking his head, “they are of no use to me. I cannot forgive you unless you bring me back my own hook.”

Nothing would appease the anger of the Skillful Fisher, for he had a bad disposition, and had always hated his brother because of his virtues, and now with the excuse of the lost fishing hook he planned to kill him and to usurp his place as ruler of Japan. The Happy Hunter knew all this full well, but he could say nothing, for being the younger he owed his elder brother

Comments (0)