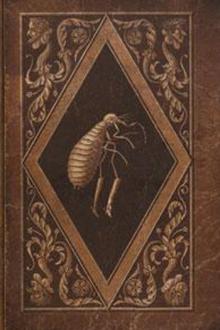

Master Flea by E. T. A. Hoffmann (i read a book txt) 📕

The elder Mr. Tyss had always considered it a bad omen that Peregrine, as a little child, should prefer counters to d

Read free book «Master Flea by E. T. A. Hoffmann (i read a book txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: E. T. A. Hoffmann

- Performer: -

Read book online «Master Flea by E. T. A. Hoffmann (i read a book txt) 📕». Author - E. T. A. Hoffmann

"Master," replied Peregrine, drawing the bed-clothes away from his face,--"dear Master, you are right: nothing is more dangerous than the temptations of women; they are all false, all malicious; they play with us as cats with mice, and for our tenderest exertions we reap nothing but contempt and mockery. Hence it is that formerly a cold deathlike perspiration used to stand upon my brow as soon as any woman-creature approached me, and I myself believe that there must be something peculiar about the fair Alina, or Princess Gamaheh, as you will have it, although, with my plain human reason, I do not comprehend all that you are saying, but rather feel as if I were in some wild dream, or reading the Thousand and One Nights. Be all this, however, as it may, you have put yourself under my protection, dear Master, and nothing shall persuade me to deliver you up to your enemies; as to the seductive maiden, I will not see her again. This I promise solemnly, and would give my hand upon it, had you one to receive it and return the honourable pledge."

With this Peregrine stretched out his arm far upon the bed-clothes.

"Now," exclaimed the little Invisible,--"now I am quite consoled, quite at ease. If I have no hand to offer you, at least permit me to prick you in the right thumb, partly to testify my extreme satisfaction, and partly to seal our bond of friendship more assuredly."

At the same moment Peregrine felt in the thumb of his right hand a bite, which smarted so sensibly, as to prove it could have come only from the first Master of all the fleas.

"You bite like a little devil!" cried Peregrine.

"Take it," replied Master Flea, "as a lively token of my honourable intentions. But it is fit that I should offer to you, as a pledge of my gratitude, a gift which belongs to the most extraordinary productions of art. It is nothing else than a microscope, made by a very dexterous optician of my people, while he was in Leuwenhock's service. The instrument will appear somewhat small to you, for, in reality, it is about a hundred and twenty times smaller than a grain of sand; but its use will not allow of any peculiar greatness. It is this: I place the glass in the pupil of your left eye, and this eye immediately becomes microscopic. As I wish to surprise you with the effect of it, I will say no more about it for the present, and will only entreat that I may be permitted to perform the microscopic operation whenever I see that it will do you any important service.--And now sleep well, Mr. Peregrine; you have need of rest."

Peregrine, in reality, fell asleep, and did not awake till full morning, when he heard the well-known scratching of old Alina's broom; she was sweeping out the next room. A little child, who was conscious of some mischief, could not tremble more at his mother's rod than Mr. Peregrine trembled in the fear of the old woman's reproaches. At length she came in with the coffee. Peregrine glanced at her through the bed-curtains, which he had drawn close, and was not a little surprised at the clear sunshine which overspread the old woman's face.

"Are you still asleep, my dear Mr. Tyss?" she asked in one of the softest tones of which her voice was capable; and Peregrine, taking courage, answered just as softly,

"No, my dear Alina: lay the breakfast upon the table; I will get up directly."

But, when he did really rise, it seemed to him as if the sweet breath of the creature, who had lain in his arms, was waving through the chamber--he felt so strangely and so anxiously. He would have given all the world to know what had become of the mystery of his passion; for, like this mystery itself, the fair one had appeared and vanished.

While he was in vain endeavouring to drink his coffee and eat his toast,--every morsel of which was bitter in his mouth,--Alina entered, and busied herself about this and that, murmuring all the time to herself--"Strange! incredible! What things one sees! Who would have thought it?"

Peregrine, whose heart beat so strongly that he could bear it no longer, asked, "What is so strange, dear Alina?"

"All manner of things! all manner of things!" replied the old woman, laughing cunningly, while she went on with her occupation of setting the rooms to rights. Peregrine's breast was ready to burst, and he involuntarily exclaimed, in a tone of languishing pain,--"Ah! Alina!"

"Yes, Mr. Tyss, here I am; what are your commands?" replied Alina, spreading herself out before Peregrine, as if in expectation of his orders.

Peregrine stared at the copper face of the old woman, and all his fears were lost in the disgust which filled him on the sudden. He asked in a tolerably harsh tone,--

"What has become of the strange lady who was here yesterday evening? Did you open the door for her? Did you look to a coach for her, as I ordered? Was she taken home?"

"Open doors!" said the old woman with an abominable grin, which she intended for a sly laugh--"Look to a coach! taken home!--There was no need of all this:--the fair damsel is in the house, and won't leave the house for the present."

Peregrine started up in joyful alarm; and she now proceeded to tell him how, when the lady was leaping down the stairs in a way that almost stunned her, Mr. Swammer stood below, at the door of his room, with an immense branch-candlestick in his hand. The old gentleman, with a profusion of bows, contrary to his usual custom, invited the lady into his apartment, and she slipt in without any hesitation, and her host locked and bolted the door.

The conduct of the misanthropic Swammer was too strange for Alina not to listen at the door, and peep a little through the keyhole. She then saw him standing in the middle of the room, and talking so wisely and pathetically to the lady, that she herself had wept, though she had not understood a single word, he having spoken in a foreign language. She could not think otherwise than that the old gentleman had laboured to bring her back to the paths of virtue, for his vehemence had gradually increased, till the damsel at last sank upon her knees and kissed his hand with great humility: she had even wept a little. Upon this he lifted her up very kindly, kissed her forehead,--in doing which he was forced to stoop terribly,--and then led her to an arm-chair. He next busied himself in making a fire, brought some spices, and, as far as she could perceive, began to mull some wine. Unluckily the old woman had just then taken snuff, and sneezed aloud; upon which Swammer, stretching out his arm to the door, exclaimed with a terrible voice, that went through the marrow of her bones, "Away with thee, listening Satan!"--She knew not how she had got off and into her bed; but in the morning, upon opening her eyes, she fancied she saw a spectre; for before her stood Mr. Swammer in a handsome sable-fur, with gold buckles, his hat on his head, his stick in his hand.

"My good Mistress Alina," he said, "I must go out on important business, and perhaps may not return for many hours. Take care, therefore, that there is no noise on my floor, and that no one ventures to enter my room. A lady of rank, and--I may tell you,--a very handsome princess, has taken refuge with me. Long ago, at the court of her father, I was her governor; therefore she has confidence in me, and I must and will protect her against all evil machinations. I tell you this, Mistress Alina, that you may show the lady the respect which belongs to her rank. With Mr. Tyss's permission she will be waited on by you, for which attendance you will be royally rewarded, provided you are silent, and do not betray the princess' abode to any one." So saying, Mr. Swammer had immediately gone off.

Peregrine now asked the old woman, if it did not seem strange that the lady, whom he could swear he met at the bookbinder's, should be a princess, seeking refuge with old Swammer? But she protested that she believed his words rather than her own eyes, and was therefore of opinion that all, which had happened at the bookbinder's or in the chamber, was either a magical illusion, or that the terror and anxiety of the flight had led the princess into so strange an adventure. For the rest, she would soon learn all from the lady herself.

"But," objected Peregrine, in reality only to continue the conversation about the lady, "but where is the suspicion, the evil opinion, you had of her yesterday?"

"Ah," replied the old woman simpering, "that is all over. One need only look at the dear creature to be convinced she is a princess, and as beautiful withal as ever was princess. When Swammer had gone, I could not help looking to see what she was about, and peeping a little through the key-hole. There she lay stretched out upon the sofa, her angel head leaning upon her hand, so that the raven locks poured through the little white fingers, a beautiful sight! Her dress was of silver tissue, through which the bosom and the arms were visible, and on her feet she had golden slippers. One had fallen off, and showed that she wore no stockings, so that the naked foot peeped forth from under the garments. But, my good Mr. Tyss, she is no doubt still lying on the sofa; and if you will take the trouble of peeping through the key-hole----"

"What do you say?" interrupted Peregrine with vehemence; "what do you say? Shall I expose myself to her seductive sight, which might urge me into all manner of follies?"

"Courage, Peregrine! resist the temptation!" lisped a voice close beside him, which he instantly recognised for that of Master Flea.

The old woman laughed mysteriously, and after a few minutes' silence said,--"I will tell you the whole matter, as it seems to me. Whether the strange lady be a princess or not, thus much is certain, that she is of rank and rich, and that Mr. Swammer has taken up her cause warmly, and must have been long acquainted with her. And why did she run after you, dear Mr. Tyss? I say, because she is desperately in love with you, and love makes people blind and mad, and leads even princesses into the strangest and most inconsiderate follies. A gipsy prophesied to your late mother that you would one day be happy in a marriage when you least expected it. Now it is coming true."

And with this the old woman began again describing how beautiful the lady looked. It may be easily supposed that Peregrine felt overwhelmed. At last he broke out with, "Silence, I pray you, of such things. The lady in love with me! How silly! how absurd!"

"Umph!" said the old woman; "if that were not the case she would not have sighed so piteously, she would not have exclaimed so lamentably,

Comments (0)