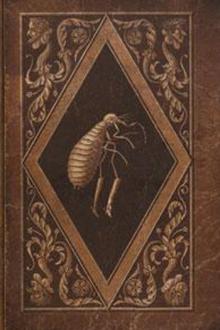

Master Flea by E. T. A. Hoffmann (i read a book txt) 📕

The elder Mr. Tyss had always considered it a bad omen that Peregrine, as a little child, should prefer counters to d

Read free book «Master Flea by E. T. A. Hoffmann (i read a book txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: E. T. A. Hoffmann

- Performer: -

Read book online «Master Flea by E. T. A. Hoffmann (i read a book txt) 📕». Author - E. T. A. Hoffmann

"I thank you much, my best Mr. Tyss, for your favourable opinion, and hope soon to convince you that you are not mistaken in me. In the meantime, that you may learn what service you have rendered me, it is requisite that I should impart to you my whole history. Know, then, that my father was the renowned----yet stay; it just occurs to me, that the beautiful gift of patience has become remarkably rare of late amongst readers and auditors, and that copious memoirs, once so much admired, are now detestable: I will therefore touch lightly and episodically that part only which is more immediately connected with my abode with you. In knowing that I am really Master Flea, you must know me for a man of the most extensive learning, of the most profound experience in all branches of knowledge. But hold! You cannot measure the degree of my information by your scale, since you are ignorant of the wonderful world in which I and my people live. How would you feel astonished if your mind could be opened to that world! it would seem to you a realm of the strangest and most incomprehensible wonders, and hence you must not feel surprised, if all which originates from that world should seem to you like a confused fairy-tale, invented by an idle brain. Do not, therefore, allow yourself to be confounded, but trust my words.--See; in many things my people are far superior to you men; for example--in all that regards the penetrating into the mysteries of nature, in strength, dexterity,--spiritual and corporeal dexterity. But we, too, have our passions; and with us, as with you, these are often the sources of great disquietudes, sometimes even of total destruction. Loved, nay adored, as I was, by my people, my mastery might have placed me upon the pinnacle of happiness, had I not been blinded by an unfortunate passion for a person who completely governed me, though she never could be my wife. But our race is in general reproached with a passion for the fair sex, that oversteps the bounds of decorum. Supposing, however, this reproach to be true, yet, on the other hand, every one knows----but hold--without more circumlocution--I saw the daughter of King Sekakis, the beautiful Gamaheh, and on the instant became so desperately enamoured of her, that I forgot my people, myself, and lived only in the delight of skipping about the fairest neck, the fairest bosom, and tickling the beauty with kisses. She often caught at me with her rosy fingers, without ever being able to seize me, and this I took for the toying of affection. But how silly is any one in love, even when that one is Master Flea. Suffice it to say, that the odious Leech-Prince fell upon the poor Gamaheh, whom he kissed to death; but still I should have succeeded in saving my beloved, if a silly boaster and an awkward ideot had not interfered without being asked, and spoilt all. The boaster was the Thistle, Zeherit, and the ideot was the Genius, Thetel. When, however, the Genius rose in the air with the sleeping princess, I clung fast to the lace about her bosom, and thus was Gamaheh's faithful fellow-traveller, without being perceived by him. It happened that we flew over two magi, who were observing the stars from a lofty tower. One of them directed his glass so sharply at me, that I was almost blinded by the shine of the magic instrument. A violent giddiness seized me; in vain I sought to hold fast; I tumbled down helplessly from the monstrous height, fell plump upon the nose of one of the magi, and only my lightness, my extraordinary activity, could have saved me.

"I was still too much stunned to skip off his nose and place myself in perfect safety, when the treacherous Leuwenhock,--he was the magician,--caught me dexterously with his fingers, and placed me in his microscope. Notwithstanding it was night, and he was obliged to use a lamp, he was by far too practiced an observer, and too great an adept, not immediately to recognise in me the Master Flea. Delighted that a lucky chance had delivered into his hands such an important prisoner, and resolved to draw every possible advantage from it, he flung poor me into chains, and thus began a painful imprisonment, from which I was yesterday freed by you. The possession of me gave the abominable Leuwenhock full power over my vassals, whom he soon collected in swarms about him, and with barbarian cruelty introduced amongst us that which is called education, and which soon robbed us of all freedom, of all enjoyment of life. In regard to scholastic studies, and the arts and sciences in general, Leuwenhock soon discovered, to his surprise and vexation, that we knew more than himself; the higher cultivation which he forced upon us consisted chiefly in this:--that we were to be something, or at least represent something. But it was precisely this being something, this representing something, that brought with it a multitude of wants which we had never known before, and which were now to be satisfied with the sweat of our brow. The barbarous Leuwenhock converted us into statesmen, soldiers, professors, and I know not what besides. All were obliged to wear the dress of their respective ranks, and thus arose amongst us tailors, shoemakers, hairdressers, blacksmiths, cutlers, and a multitude of other trades, only to satisfy an useless and destructive luxury. The worst of it was, that Leuwenhock had nothing else in view than his own advantage in showing us cultivated people to men, and receiving money for it. Moreover our cultivation was set down entirely to his account, and he got the praise which belonged to us alone. Leuwenhock well knew that in losing me he would also lose the dominion over my people; the more closely therefore he drew the spell which bound me to him, and so much the harder was my imprisonment. I thought with ardent desire on the beautiful Gamaheh, and pondered on the means of getting tidings of her fate; but what the acutest reason could not effect, the chance of the moment itself brought about. The friend and associate of my magician, the old Swammerdamm, had found the princess in the petal of a tulip, and this discovery he imparted to his friend. By means, which, my good Peregrine, I forbear detailing to you, as you do not understand much about these matters, he succeeded in restoring Gamaheh to her natural shape, and bringing her back to life. In the end, however, these very wise persons proved as awkward ideots as the Genius, Thetel, and the Thistle, Zeherit. In their eagerness they had forgotten the most material point, and thus it happened that in the very same moment the princess awoke to life, she was sinking back again into death. I alone knew the cause; love to the fair one, which now flamed in my breast stronger than ever, gave me a giant's strength; I burst my chains--sprang with one mighty bound upon her shoulder--a single bite sufficed to set the freezing blood in motion--she lived. But I must tell you, Mr. Peregrine Tyss, that this bite must be repeated if the princess is to continue blooming in youth and beauty; otherwise she will dwindle away in a few months to a shrivelled little old woman. On this account, as you must see, I am quite indispensable to her; and it is only by the fear of losing me, that I can account for the black ingratitude with which she repaid my love. Without more ado she delivered me up to my tormentor, who flung me into heavier chains than ever, but to his own destruction. In spite of all the vigilance of Leuwenhock and Gamaheh, I at last succeeded, in an unguarded hour, in escaping from my prison. Although the heavy boots, which I had no time to pull off, hindered me considerably in my flight, yet I got safely to the shop of the toyman, of whom you bought your ware; but it was not long, before, to my infinite terror, Gamaheh entered the shop. I held myself lost; you alone could save me: I gently whispered to you my distress, and you were good enough to open a little box for me, into which I quickly sprang, and in which you as quickly carried me off with you. Gamaheh sought in vain for me, and it was not till much later that she learnt how and whither I had fled.

"As soon as I was free, Leuwenhock lost all power over my people, who immediately slipt away, and in mockery left the tyrant peppercorns, fruitstones, and such like, in their clothes. Again, then, my hearty thanks, kind, noble Mr. Peregrine, for the great benefit you have done me, and which I know as well as any one how to estimate. Permit me, as a free man, to remain a little time with you; I can be useful to you in many important affairs of your life beyond what you may expect. To be sure there might be danger if you should become enamoured of the fair one,----"

"What do you say?" interrupted Peregrine; "what do you say, Master? I, I enamoured!"

"Even so;" continued Master Flea: "think of my terror, of my anxiety, when you entered yesterday with the princess in your arms, glowing with passion, and she employing every seductive art--as she well knows how--to persuade you to surrender me. Ah, then I perceived your nobleness in its full extent, when you remained immoveable, dexterously feigning as if you knew nothing of my being with you, as if you did not even understand what the princess wanted."

"And that was precisely the truth of the matter," said Peregrine, interrupting Master Flea anew. "You are attributing things as a merit to me, of which I had not the slightest suspicion. In the shop where I bought the toys, I neither saw you nor the fair damsel, who sought me at the bookbinder's, and whom you are strangely pleased to call the Princess Gamaheh. It was quite unknown to me, that amongst the boxes, where I expected to find leaden soldiers, there was an empty one in which you were lurking; and how could I possibly guess that you were the prisoner whom the pretty child was requiring with such impetuosity?--Don't be whimsical, Master Flea, and dream of things, of which I had not the slightest conception."

"Ah," replied Master Flea, "you would dexterously avoid my thanks, kind Mr. Peregrine; and this gives me, to my great consolation, a farther lively proof of your noble way of thinking. Learn, generous man, that all the efforts of Leuwenhock and Gamaheh to regain me are fruitless, so long as you afford me your protection: you must voluntarily give me up to my tormentors; all other means are to no purpose--Mr. Peregine Tyss, you are in love!"

"Do not talk so!" exclaimed Peregrine. "Do not call by the name of love a foolish momentary ebullition, which is already past."

Peregrine felt the colour rushing up into his cheeks and forehead, and giving him the lie. He crept under the bed-clothes. Master Flea continued:

"It is not to be wondered at if you were unable to resist the surprising charms of the princess, especially as she employed many dangerous arts to captivate you. Nor is the storm yet over. The malicious little thing will put in practice many a trick to catch you in her love-toils, as, indeed, every woman can, without exactly being a Princess Gamaheh. She will try to get you

Comments (0)