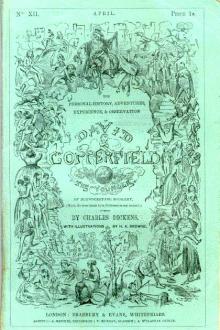

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (sites to read books for free txt) 📕

I need say nothing here, on the first head, because nothing can show better than my history whether that prediction was verified or falsified by the result. On the second branch of the question, I will only remark, that unless I ran through that part of my inheritance while I was still a baby, I have not come into it yet. But I do not at all complain of having been kept out of this property; and if anybody else should be in the present enjoyment of it, he is heartily welcome to keep it.

I was born with a caul, which was advertised for sale, in the newspapers, at the low price of fifteen guineas. Whether sea-going people were short of money about that time, or were short of faith and preferred cork jackets, I don't know; all I know is, that there was but one solitary bidding, and that was from an attorney connected with the bill-broking business, who offered two pounds in cash, and the balance in sherry, but declined to be guaranteed from drowning on any hig

Read free book «David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (sites to read books for free txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: 0679783415

Read book online «David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (sites to read books for free txt) 📕». Author - Charles Dickens

‘It is humble,’ said Mr. Micawber, ‘- to quote a favourite expression of my friend Heep; but it may prove the stepping-stone to more ambitious domiciliary accommodation.’

I asked him whether he had reason, so far, to be satisfied with his friend Heep’s treatment of him? He got up to ascertain if the door were close shut, before he replied, in a lower voice:

‘My dear Copperfield, a man who labours under the pressure of pecuniary embarrassments, is, with the generality of people, at a disadvantage. That disadvantage is not diminished, when that pressure necessitates the drawing of stipendiary emoluments, before those emoluments are strictly due and payable. All I can say is, that my friend Heep has responded to appeals to which I need not more particularly refer, in a manner calculated to redound equally to the honour of his head, and of his heart.’

‘I should not have supposed him to be very free with his money either,’ I observed.

‘Pardon me!’ said Mr. Micawber, with an air of constraint, ‘I speak of my friend Heep as I have experience.’

‘I am glad your experience is so favourable,’ I returned.

‘You are very obliging, my dear Copperfield,’ said Mr. Micawber; and hummed a tune.

‘Do you see much of Mr. Wickfield?’ I asked, to change the subject.

‘Not much,’ said Mr. Micawber, slightingly. ‘Mr. Wickfield is, I dare say, a man of very excellent intentions; but he is - in short, he is obsolete.’

‘I am afraid his partner seeks to make him so,’ said I.

‘My dear Copperfield!’ returned Mr. Micawber, after some uneasy evolutions on his stool, ‘allow me to offer a remark! I am here, in a capacity of confidence. I am here, in a position of trust. The discussion of some topics, even with Mrs. Micawber herself (so long the partner of my various vicissitudes, and a woman of a remarkable lucidity of intellect), is, I am led to consider, incompatible with the functions now devolving on me. I would therefore take the liberty of suggesting that in our friendly intercourse - which I trust will never be disturbed! - we draw a line. On one side of this line,’ said Mr. Micawber, representing it on the desk with the office ruler, ‘is the whole range of the human intellect, with a trifling exception; on the other, IS that exception; that is to say, the affairs of Messrs Wickfield and Heep, with all belonging and appertaining thereunto. I trust I give no offence to the companion of my youth, in submitting this proposition to his cooler judgement?’

Though I saw an uneasy change in Mr. Micawber, which sat tightly on him, as if his new duties were a misfit, I felt I had no right to be offended. My telling him so, appeared to relieve him; and he shook hands with me.

‘I am charmed, Copperfield,’ said Mr. Micawber, ‘let me assure you, with Miss Wickfield. She is a very superior young lady, of very remarkable attractions, graces, and virtues. Upon my honour,’ said Mr. Micawber, indefinitely kissing his hand and bowing with his genteelest air, ‘I do Homage to Miss Wickfield! Hem!’ ‘I am glad of that, at least,’ said I.

‘If you had not assured us, my dear Copperfield, on the occasion of that agreeable afternoon we had the happiness of passing with you, that D. was your favourite letter,’ said Mr. Micawber, ‘I should unquestionably have supposed that A. had been so.’

We have all some experience of a feeling, that comes over us occasionally, of what we are saying and doing having been said and done before, in a remote time - of our having been surrounded, dim ages ago, by the same faces, objects, and circumstances - of our knowing perfectly what will be said next, as if we suddenly remembered it! I never had this mysterious impression more strongly in my life, than before he uttered those words.

I took my leave of Mr. Micawber, for the time, charging him with my best remembrances to all at home. As I left him, resuming his stool and his pen, and rolling his head in his stock, to get it into easier writing order, I clearly perceived that there was something interposed between him and me, since he had come into his new functions, which prevented our getting at each other as we used to do, and quite altered the character of our intercourse.

There was no one in the quaint old drawing-room, though it presented tokens of Mrs. Heep’s whereabouts. I looked into the room still belonging to Agnes, and saw her sitting by the fire, at a pretty old-fashioned desk she had, writing.

My darkening the light made her look up. What a pleasure to be the cause of that bright change in her attentive face, and the object of that sweet regard and welcome!

‘Ah, Agnes!’ said I, when we were sitting together, side by side; ‘I have missed you so much, lately!’

‘Indeed?’ she replied. ‘Again! And so soon?’

I shook my head.

‘I don’t know how it is, Agnes; I seem to want some faculty of mind that I ought to have. You were so much in the habit of thinking for me, in the happy old days here, and I came so naturally to you for counsel and support, that I really think I have missed acquiring it.’

‘And what is it?’ said Agnes, cheerfully.

‘I don’t know what to call it,’ I replied. ‘I think I am earnest and persevering?’

‘I am sure of it,’ said Agnes.

‘And patient, Agnes?’ I inquired, with a little hesitation.

‘Yes,’ returned Agnes, laughing. ‘Pretty well.’

‘And yet,’ said I, ‘I get so miserable and worried, and am so unsteady and irresolute in my power of assuring myself, that I know I must want - shall I call it - reliance, of some kind?’

‘Call it so, if you will,’ said Agnes.

‘Well!’ I returned. ‘See here! You come to London, I rely on you, and I have an object and a course at once. I am driven out of it, I come here, and in a moment I feel an altered person. The circumstances that distressed me are not changed, since I came into this room; but an influence comes over me in that short interval that alters me, oh, how much for the better! What is it? What is your secret, Agnes?’

Her head was bent down, looking at the fire.

‘It’s the old story,’ said I. ‘Don’t laugh, when I say it was always the same in little things as it is in greater ones. My old troubles were nonsense, and now they are serious; but whenever I have gone away from my adopted sister -‘

Agnes looked up - with such a Heavenly face! - and gave me her hand, which I kissed.

‘Whenever I have not had you, Agnes, to advise and approve in the beginning, I have seemed to go wild, and to get into all sorts of difficulty. When I have come to you, at last (as I have always done), I have come to peace and happiness. I come home, now, like a tired traveller, and find such a blessed sense of rest!’

I felt so deeply what I said, it affected me so sincerely, that my voice failed, and I covered my face with my hand, and broke into tears. I write the truth. Whatever contradictions and inconsistencies there were within me, as there are within so many of us; whatever might have been so different, and so much better; whatever I had done, in which I had perversely wandered away from the voice of my own heart; I knew nothing of. I only knew that I was fervently in earnest, when I felt the rest and peace of having Agnes near me.

In her placid sisterly manner; with her beaming eyes; with her tender voice; and with that sweet composure, which had long ago made the house that held her quite a sacred place to me; she soon won me from this weakness, and led me on to tell all that had happened since our last meeting.

‘And there is not another word to tell, Agnes,’ said I, when I had made an end of my confidence. ‘Now, my reliance is on you.’

‘But it must not be on me, Trotwood,’ returned Agnes, with a pleasant smile. ‘It must be on someone else.’

‘On Dora?’ said I.

‘Assuredly.’

‘Why, I have not mentioned, Agnes,’ said I, a little embarrassed, ‘that Dora is rather difficult to - I would not, for the world, say, to rely upon, because she is the soul of purity and truth - but rather difficult to - I hardly know how to express it, really, Agnes. She is a timid little thing, and easily disturbed and frightened. Some time ago, before her father’s death, when I thought it right to mention to her - but I’ll tell you, if you will bear with me, how it was.’

Accordingly, I told Agnes about my declaration of poverty, about the cookery-book, the housekeeping accounts, and all the rest of it.

‘Oh, Trotwood!’ she remonstrated, with a smile. ‘Just your old headlong way! You might have been in earnest in striving to get on in the world, without being so very sudden with a timid, loving, inexperienced girl. Poor Dora!’

I never heard such sweet forbearing kindness expressed in a voice, as she expressed in making this reply. It was as if I had seen her admiringly and tenderly embracing Dora, and tacitly reproving me, by her considerate protection, for my hot haste in fluttering that little heart. It was as if I had seen Dora, in all her fascinating artlessness, caressing Agnes, and thanking her, and coaxingly appealing against me, and loving me with all her childish innocence.

I felt so grateful to Agnes, and admired her so! I saw those two together, in a bright perspective, such well-associated friends, each adorning the other so much!

‘What ought I to do then, Agnes?’ I inquired, after looking at the fire a little while. ‘What would it be right to do?’

‘I think,’ said Agnes, ‘that the honourable course to take, would be to write to those two ladies. Don’t you think that any secret course is an unworthy one?’

‘Yes. If YOU think so,’ said I.

‘I am poorly qualified to judge of such matters,’ replied Agnes, with a modest hesitation, ‘but I certainly feel - in short, I feel that your being secret and clandestine, is not being like yourself.’

‘Like myself, in the too high opinion you have of me, Agnes, I am afraid,’ said I.

‘Like yourself, in the candour of your nature,’ she returned; ‘and therefore I would write to those two ladies. I would relate, as plainly and as openly as possible, all that has taken place; and I would ask their permission to visit sometimes, at their house. Considering that you are young, and striving for a place in life, I think it would be well to say that you would readily abide by any conditions they might impose upon you. I would entreat them not to dismiss your request, without a reference to Dora; and to discuss it with her when they should think the time suitable. I would not be too vehement,’ said Agnes, gently, ‘or propose too much. I would trust to my fidelity and perseverance - and to Dora.’

‘But if they were to frighten Dora again, Agnes, by speaking to her,’ said I. ‘And if Dora were to cry, and say nothing about me!’

‘Is that likely?’ inquired Agnes, with the same sweet consideration in her face.

‘God bless her, she is as easily scared as a bird,’ said I. ‘It might be! Or if the two

Comments (0)