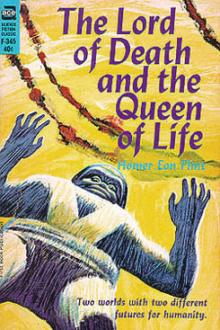

The Devolutionist and the Emancipatrix by Homer Eon Flint (recommended reading txt) 📕

Read free book «The Devolutionist and the Emancipatrix by Homer Eon Flint (recommended reading txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

Read book online «The Devolutionist and the Emancipatrix by Homer Eon Flint (recommended reading txt) 📕». Author - Homer Eon Flint

"But when it comes to leaving the solar system entirely the telepathic method is the only one that will work; even the nearest of the fixed stars is out of the question."

"How far is that?" Smith inquired.

"The nearest? About four and a half light-years."

"Yes, but what's a light-year?"

"It amounts to sixty-three thousand times the distance from here to the sun!"

Smith whistled. "Nothing doing in the cube, that's sure. Besides, could we expect to find any people like us in the neighborhood of that star?"

"Not Alpha Centauri." The doctor reached for one of the Venusian books, and pointed out certain pages. "It seems that the Class IIa stars—that is, suns—are the only ones which have planets in the right condition for the development of humans. The astronomers already suspected as much, by the way. But the Venusians have definitely named a few systems whose evolution has reached points almost identical with that of the earth.

"Now, until we have acquired a certain amount of ability" —examining the books more closely—"our best chance will lie in the neighborhood of a giant star known to us as Capella."

"Capella." Billie had drawn a star-chart to her side. "Where is that located?"

"In Auriga, about half-way from Orion to the Pole Star. She's a big yellow sun.

"At any rate, the Venusians say that this particular planet of Capella's has people almost exactly the same as those of the earth, except"—speaking very clearly—"except that they have had about one century more civilization!"

Billie exclaimed with delight. "Say—this is going to be the best yet! To think of seeing what the earth is going to be like, a hundred years from now!"

Instantly Van Emmon's interest became acute. "By George! Is that right, doc? Are we likely to learn what the next hundred years will do for us?"

"Don't know exactly." The doctor spoke cautiously. "That's merely what I infer from these books."

"If we do," ran on the geologist excitedly, "we'll see how a lot of our present day theories will be worked out! I'm curious to see what comes of them. Personally, I think most of them are plain nonsense!"

"That remains to be seen." The doctor glanced around. "Remember: what we want is the view-point only; and the place is Capella's planetary system. Ready?"

For answer the others leaned back in their chairs. The doctor touched the button at his side, as a signal to his wife; he settled himself in his chair; and in a minute his head was dropping over against his shoulder. In another second the minds of the four experimenters were out of their bodies; out, and in the twinkling of an eye, traversing space at absolute speed.

For thought, like gravitation, is instantaneous.

III SMITH'S MIND WANDERSSecretly Smith hoped he might find an agent who also was an engineer. He had this in mind all the while he was repeating the Venusian formula, the sequence of thought-images which was necessary to bring on the required state of mind. The formula had the effect of closing his mind to all save telepathic energy, and opening wide the channels through which it controlled the brain.

No sooner had he repeated the words, meanwhile concentrating with all the force of his newly trained will upon the single idea of seeing and hearing what was happening on the unknown, yet quite knowable planet—no sooner had his head sunk on his chest than he became aware of a strange sound.

On all sides unseen apparatus gave forth a medley of subdued jars and clankings. A variety of hissing sounds also were distinguishable. And meanwhile Smith was staring hard, with the eyes he had borrowed along with the ears, at a pair of human hands.

These hands were manipulating a group of highly polished levers and hand-wheels. So long as his borrowed sight was fixed upon that group Smith was entirely ignorant of the surroundings. All he could surmise was that his agents operated some sort of machinery.

Then the agent glanced up; and Smith got his first shock. For he now saw a cluster of indicating dials, such as one may see on the instrument board of any automobile; but the trained engineer found himself absolutely unable to interpret one of them. They were marked with unknown figures!

Nevertheless, the engineer received an unmistakable impression, quite as vivid as though something had been said aloud. "Progress; all safe," was the thought-image that came to him.

He listened closely in hope of hearing a spoken word. Also, he tried his best to make his agent look around the place. Other people might be within sight. However, for a couple of minutes the oddly familiar hands kept manipulating the unfamiliar instruments.

Then, somewhere quite close at hand, a deep-toned gong sounded a single stroke. Instantly the agent looked up; and Smith saw that he was inspecting the interior of a large engine-room. He had time to note the huge bulk of a horizontal cylinder, perhaps fifty feet in diameter, in the immediate background; also a variety of other mechanisms, more like immensely enlarged editions of laboratory apparatus than ordinary engines. Smith looked in vain for the compact form of a dynamo or motor, and listened in vain for the sound of either. Then, in swift succession, came two strokes on the unseen gong, followed by a shrill whistle.

Smith's borrowed eyes became fixed upon that group of dials again. Their indicators began to shift, some rapidly, some slowly. Once the agent gave a swift glance through a round window—the place seemed to be lighted by ordinary daylight—and Smith saw something unrecognizable flit by.

A little further progress, and then came three strokes on the gong, followed by a low thrumming. In response to these, the agent deliberately picked out two levers, and pulled them down. When his glance returned to the dials, one of them showed immense acceleration.

By and by came another triple clanging, another pair of levers was pulled down, and instantly the jarring and clanking gave way to a decided rumble, low and distinct, but so powerful that it shook the air. At the same time the agent quit his post and went over to the giant horizontal cylinder.

Now Smith could see that this vast structure was merely part of an engine whose dimensions were quite beyond any former experience. It was a simple affair, being merely a reciprocal machine like the most elementary form of steam engine. But, instead of being operated by steam, it was a chemical machine; Smith's trained eyes told him that the cylinder was really an enormous retort. And he noted with further perplexity that the prodigious piston-rod not only moved with terrific speed, but in a strictly back-and-forth motion; its far end did not revolve.

The agent seemed satisfied with it all. He turned about and walked—so far as Smith could sense in the usual manner of earth's humans—back to the dials again. Just then a door opened a short distance away and another man entered.

Smith would have mistaken him for the employee of some garage. He was dressed in a suit of greasy blue overalls; and as he advanced toward the eyes Smith was using, he looked about the room with practiced glance. He merely nodded to Smith's man, who returned the nod just as silently; and such was the extreme brevity of it all, Smith was afterward unable to describe the man.

His agent, thus relieved of his duty temporarily, strolled out another door, which took him through a narrow corridor and another door, opening on to some sort of a balcony, or deck. Smith fully expected to look upon an ocean.

Instead, he found himself gazing into a sea of clouds. He was in some sort of aircraft!

Next moment, quite as though it had all been prearranged, a large sky-cruiser hove into sight perhaps a quarter of a mile away. It seemed to materialize out of the clouds, and rapidly bore down upon the craft in which the agent stood.

But the practical man of the earth was eying the air-ship in increasing amazement. For it was truly a ship; a huge vessel wonderfully like one of the old-fashioned freighters which used to sail the seas of the earth. What was more, it had four tall, sloping masts, each spread with something remarkably like canvas; and that whole incredible hulk was actually swinging in mid air!

Looking closer, Smith saw that the masts were exceedingly tall; they held enough canvas to propel ten ships. And each stick sloped back at so sharp an angle—much sharper than forty-five degrees—that the wind not only blew the craft along in its course, but actually supported it as well.

It meant a wind which would make a hurricane seem tame. Either that, or air with greater density than any Smith knew about.

Suddenly the cruiser came about into the wind, and at the same instant it began to take in sail, all the sheets furling in unison. Simultaneously great finlike wings shot out of slits in the sides of the hull; and immediately they began to beat the air, back and forth, back and forth, with the speed and motion of swallows.

So this was the meaning of the giant reciprocal engine! Instead of the screw propeller which characterized earth's aircraft, these vessels employed the true bird principle, combining it with the simple methods of primitive sailing craft.

As soon as the ship stopped its wind-driven rush and began to employ its wings, the speed straightway slackened; and the ships began to descend. About the same time the figures of several people appeared on what might be called the bridge; and assuming that these people were as large as the man whom Smith had seen enter the engine-room—a chap of average height—then that ship, in proportion, was all of a mile long!

But Smith's awe was not shared by his agent, who turned indifferently away and looked about the sky as though in search of other sights. In doing so, he leaned over the deck's railing; and Smith saw the sheer sides of the giant ship, extending fore and aft almost indefinitely; while far overhead billowed vast clouds of white cloth. The vessel was now under sail.

About a mile higher up, and almost that distance to one side, the agent's eyes made out two tiny specks. He watched them closely for a moment as they pitched and tossed queerly about; then darted into the engine-room, secured a pair of binoculars of an old, squat pattern, and swiftly focused upon the nearer of the two.

Smith instantly sensed a disaster. The object was a small air-craft, of a sort entirely strange to the engineer; yet he knew that it was disabled. One of its queer wings was broken and fluttering, as the little machine dropped, tumbling and twisting erratically, in an inexplicably slow fashion toward the unseen ground. Smith glimpsed a single figure, presumably strapped in the seat.

Then the focus changed to cover the other machine. It was of the same type; and Smith saw that it was swooping in a steep spiral, its driver leaning over in his seat, looking down.

Next moment the two were in focus together. Every second they dropped closer and closer to Smith's borrowed eyes. And in less time than it takes to tell it, they had come so close that when the occupant of the disabled craft lurched heavily to one side, Smith could plainly make out the long, flying hair of a woman.

She was unconscious, and strapped in!

Her craft capsized. At the same time the other driver—a man—maneuvered so as to spiral exactly around the wreck as it fell. When it came right side up again—now only a half a mile away—he drove down so close that his machine nearly grazed the woman's head. As he did so, he leaned over and tried to unfasten her. But the unsteadiness of her craft prevented this.

He made a second try. This time his own machine narrowly escaped injury; he steered it hastily away from that damaged wing. And then he made a supreme effort.

Bringing his machine directly across the top of the other as it once more righted itself, he touched one of his controls, so that his own flier's spiral increased in steepness. Straightening up, he poised himself while he coolly measured the distance; and then he calmly leaped a matter of ten or twelve feet, over and down to the top of the other craft.

The shock of his landing steadied it. Clinging fast with one hand, the man bent and unbuckled the woman's strap. Next instant he had lifted her, a dead weight, into his arms and then

Comments (0)