The Adventures of Odysseus and The Tales of Troy by Padraic Colum (people reading books TXT) 📕

All the wooers marvelled that Telemachus spoke so boldly. And one said,'Because his father, Odysseus, was king, this youth thinks he should beking by inheritance. But may Zeus, the god, never grant that he beking.'

Then said Telemachus, 'If the god Zeus should grant that I be King, I amready to take up the Kingship of the land of Ithaka with all its toilsand all its dangers.' And when Telemachus said that he looked like ayoung king indeed.

But they sat in peace and listened to what the minstrel sang. And whenevening came the wooers left the hall and went each to his own house.Tele

Read free book «The Adventures of Odysseus and The Tales of Troy by Padraic Colum (people reading books TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Padraic Colum

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Adventures of Odysseus and The Tales of Troy by Padraic Colum (people reading books TXT) 📕». Author - Padraic Colum

The fighters faced each other. But Odysseus with his hands upraised stood for long without striking, for he was pondering whether he should strike Irus a hard or a light blow. It seemed to him better to strike him lightly, so that his strength should not be made a matter for the wooers to note and wonder at. Irus struck first. He struck Odysseus on the shoulder. Then Odysseus aimed a blow at his neck, just below the ear, and the beggar fell to the ground, with the blood gushing from his mouth and nose.

The wooers were not sorry for Irus. They laughed until they were ready to fall backwards. Then Odysseus seized Irus by the feet, and dragged him out of the house, and to the gate of the courtyard. He lifted him up and put him standing against the wall. Placing the staff in the beggar's hands, he said, 6 Sit there, and scare off the dogs and swine, and do not let such a one as you lord it over strangers. A worse thing might have befallen you.'

Then back he went to the hall, with his beggar's bag on his shoulder and his clothes more ragged than ever. Back he went, and when the wooers saw him they burst into peals of laughter and shouted out:

'May Zeus, O stranger, give thee thy dearest wish and thy heart's desire. Thou only shalt be beggar in Ithaka.' They laughed and laughed again when Antinous brought out the great pudding that was the prize. Odysseus took it from him. And another of the wooers pledged him in a golden cup, saying, 'May you come to your own, O beggar, and may happiness be yours in time to come.'

While these things were happening, the wife of Odysseus, the lady Penelope, called to Eurycleia, and said, 'This evening I will go into the hall of our house and speak to my son, Telemachus. Bid my two handmaidens make ready to come with me, for I shrink from going amongst the wooers alone.'

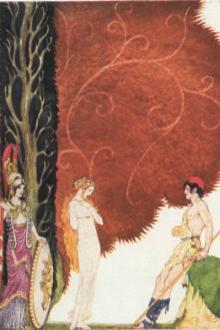

Eurycleia went to tell the handmaidens and Penelope washed off her cheeks the traces of the tears that she had wept that day. Then she sat down to wait for the handmaidens to come to her. As she waited she fell into a deep sleep. And as she slept, the goddess Pallas Athene bathed her face in the Water of Beauty and took all weariness away from her body, and restored all her youthfulness to her. The sound of the handmaidens' voices as they came in awakened her, and Penelope rose up to go into the hall.

Now when she came amongst them with her two handmaidens, one standing each side of her, the wooers were amazed, for they had never seen one so beautiful. The hearts of all were enchanted with love for her, and each prayed that he might have her for his wife.

Penelope did not look on any of the wooers, but she went to her son, Telemachus, and spoke to him.

'Telemachus,' she said, 'I have heard that a stranger has been ill-treated in this house. How, my child, didst thou permit such a thing to happen?'

Telemachus said, 'My lady mother, thou hast no right to be angered at what took place in this hall.'

So they spoke to one another, mother and son. Now one of the wooers, Eurymachus by name, spoke to Penelope, saying:

'Lady, if any more than we beheld thee in the beauty thou hast now, by so many more wouldst thou have wooers to-morrow.'

'Speak not so to me, lord Eurymachus,' said Penelope, 'speak not of my beauty, which departed in the grief I felt when my lord went to the wars of Troy.'

Odysseus stood up, and gazed upon his wife who was standing amongst her wooers. Eurymachus noted him and going to him, said, 'Stranger, wouldst thou be my hireling? If thou wouldst work on my upland farm, I should give thee food and clothes. But I think thou art practised only in shifts and dodges, and that thou wouldst prefer to go begging thy way through the country.'

Odysseus, standing there, said to that proud wooer, 'Lord Eurymachus, if there might be a trial of labour between us two, I know which of us would come out the better man. I would that we two stood together, a scythe in the hands of each, and a good swath of meadow to be mown—then would I match with thee, fasting from dawn until evening's dark. Or would that we were set ploughing together. Then thou shouldst see who would plough the longest and the best furrow! Or would that we two were in the ways of war! Then shouldst thou see who would be in the front rank of battle. Thou dost think thyself a great man. But if Odysseus should return, that door, wide as it is, would be too narrow for thy flight.'

So angry was Eurymachus at this speech that he would have struck Odysseus if Telemachus had not come amongst the wooers, saying, 'That man must not be struck again in this hall. Sirs, if you have finished feasting, and if the time has come for you, go to your own homes, go in peace I pray you.'

All were astonished that Telemachus should speak so boldly. No one answered him back, for one said to the other, 'What he has said is proper. We have nothing to say against it. To misuse a stranger in the house of Odysseus is a shame. Now let us pour out a libation of wine to the gods, and then let each man go to his home.'

The wine was poured out and the wooers departed. Then Penelope and her handmaidens went to her own chamber and Telemachus was left with his father, Odysseus.

XIIo Telemachus Odysseus said, 'My son, we must now get the weapons out of the hall. Take them down from the walls.' Telemachus and his father took down the helmets and shields and sharp-pointed spears. Then said Odysseus as they carried them out, 'To-morrow, when the wooers miss the weapons and say, "Why have they been taken?" answer them, saying, "The smoke of the fire dulled them, and they no longer looked the weapons that my father left behind him when he went to the wars of Troy. Besides, I am fearful lest some day the company in the hall come to a quarrel, one with the other, and snatch the weapons in anger. Strife has come here already. And iron draws iron, men say."'

Telemachus carried the armour and weapons out of the hall and hid them in the women's apartment. Then when the hall was cleared he went to his own chamber.

It was then that Penelope came back to the hall to speak to the stranger. One of her handmaidens, Melantho by name, was there, and she was speaking angrily to him. Now this Melantho was proud and hard of heart because Antinous often conversed with her. As Penelope came near she was saying:

'Stranger, art thou still here, prying things out and spying on the servants? Be thankful for the supper thou hast gotten and betake thyself out of this.'

Odysseus, looking fiercely at her, said, 'Why shouldst thou speak to me in such a way? If I go in ragged clothes and beg through the land it is because of my necessity. Once I had a house with servants and with much substance, and the stranger who came there was not abused.'

The lady Penelope called to the handmaiden and said, 'Thou, Melantho, didst hear it from mine own lips that I was minded to speak to this stranger and ask him if he had tidings of my lord. Therefore, it does not become thee to revile him.' She spoke to the old nurse who had come with her, and said, 'Eurycleia, bring to the fire a bench, with a fleece upon it, that this stranger may sit and tell me his story.'

Eurycleia brought over the bench, and Odysseus sat down near the fire. Then said the lady Penelope, 'First, stranger, wilt thou tell me who thou art, and what is thy name, and thy race and thy country?'

Said Odysseus, 'Ask me all thou wilt, lady, but inquire not concerning my name, or race, or country, lest thou shouldst fill my heart with more pains than I am able to endure. Verily I am a man of grief. But hast thou no tale to tell me? We know of thee, Penelope, for thy fame goes up to heaven, and no one of mortal men can find fault with thee.'

Then said Penelope, 'What excellence I had of face or form departed from me when my lord Odysseus went from this hall to the wars of Troy. And since he went a host of ills has beset me. Ah, would that he were here to watch over my life! The lords of all the islands around—Dulichium and Same and Zacynthus; and the lords of the land of Ithaka, have come here and are wooing me against my will. They devour the substance of this house and my son is being impoverished.'

'Long ago a god put into my mind a device to keep marriage with any of them away from me. I set up a great web upon my loom and I spoke to the wooers, saying, "Odysseus is assuredly dead, but I crave that you be not eager to speed on this marriage with me. Wait until I finish the web I am weaving. It is a shroud for Odysseus' father, and I make it against the day when death shall come to him. There will be no woman to care for Laertes when I have left his son's house, and I would not have such a hero lie without a shroud, lest the women of our land should blame me for neglect of my husband's father in his last days.'"

'So I spoke, and they agreed to wait until the web was woven. In the daytime I wove it, but at night I unravelled the web. So three years passed away. Then the fourth year came, and my wooers were hard to deal with. My treacherous handmaidens brought them upon me as I was unravelling the web. And now I cannot devise any other plan to keep the marriage away from me. My parents command me to marry one of my wooers. My son cannot long endure to see the substance of his house and field being wasted, and the wealth that should be his destroyed. He too would wish that I should marry. And there is no reason why I should not be wed again, for surely Odysseus, my lord, is dead.'

Said Odysseus, 'Thy lord was known to me. On his way to Troy he came to my land, for the wind blew him out of his course, sending him wandering past Malea. For twelve days he stayed in my city, and I gave him good entertainment, and saw that he lacked for nothing in cattle, or wine, or barley meal.'

When Odysseus was spoken of, the heart of Penelope melted, and tears ran down her cheeks. Odysseus had pity for his wife when he saw her weeping for the man who was even then sitting by her. Tears would have run down his own cheeks only that he was strong enough to hold them back.

Said Penelope, 'Stranger, I cannot help but question thee about Odysseus. What raiment had he on when thou didst see him? And what men were with him?'

aid Odysseus, 'Lady, it is hard for one

Comments (0)