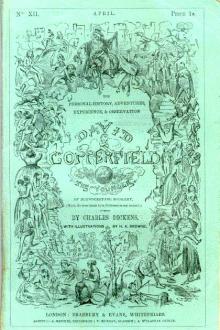

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (sites to read books for free txt) 📕

I need say nothing here, on the first head, because nothing can show better than my history whether that prediction was verified or falsified by the result. On the second branch of the question, I will only remark, that unless I ran through that part of my inheritance while I was still a baby, I have not come into it yet. But I do not at all complain of having been kept out of this property; and if anybody else should be in the present enjoyment of it, he is heartily welcome to keep it.

I was born with a caul, which was advertised for sale, in the newspapers, at the low price of fifteen guineas. Whether sea-going people were short of money about that time, or were short of faith and preferred cork jackets, I don't know; all I know is, that there was but one solitary bidding, and that was from an attorney connected with the bill-broking business, who offered two pounds in cash, and the balance in sherry, but declined to be guaranteed from drowning on any hig

Read free book «David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (sites to read books for free txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: 0679783415

Read book online «David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (sites to read books for free txt) 📕». Author - Charles Dickens

For the same reason, added no doubt to the old dislike of her, I was seldom allowed to visit Peggotty. Faithful to her promise, she either came to see me, or met me somewhere near, once every week, and never empty-handed; but many and bitter were the disappointments I had, in being refused permission to pay a visit to her at her house. Some few times, however, at long intervals, I was allowed to go there; and then I found out that Mr. Barkis was something of a miser, or as Peggotty dutifully expressed it, was ‘a little near’, and kept a heap of money in a box under his bed, which he pretended was only full of coats and trousers. In this coffer, his riches hid themselves with such a tenacious modesty, that the smallest instalments could only be tempted out by artifice; so that Peggotty had to prepare a long and elaborate scheme, a very Gunpowder Plot, for every Saturday’s expenses.

All this time I was so conscious of the waste of any promise I had given, and of my being utterly neglected, that I should have been perfectly miserable, I have no doubt, but for the old books. They were my only comfort; and I was as true to them as they were to me, and read them over and over I don’t know how many times more.

I now approach a period of my life, which I can never lose the remembrance of, while I remember anything: and the recollection of which has often, without my invocation, come before me like a ghost, and haunted happier times.

I had been out, one day, loitering somewhere, in the listless, meditative manner that my way of life engendered, when, turning the corner of a lane near our house, I came upon Mr. Murdstone walking with a gentleman. I was confused, and was going by them, when the gentleman cried:

‘What! Brooks!’

‘No, sir, David Copperfield,’ I said.

‘Don’t tell me. You are Brooks,’ said the gentleman. ‘You are Brooks of Sheffield. That’s your name.’

At these words, I observed the gentleman more attentively. His laugh coming to my remembrance too, I knew him to be Mr. Quinion, whom I had gone over to Lowestoft with Mr. Murdstone to see, before - it is no matter - I need not recall when.

‘And how do you get on, and where are you being educated, Brooks?’ said Mr. Quinion.

He had put his hand upon my shoulder, and turned me about, to walk with them. I did not know what to reply, and glanced dubiously at Mr. Murdstone.

‘He is at home at present,’ said the latter. ‘He is not being educated anywhere. I don’t know what to do with him. He is a difficult subject.’

That old, double look was on me for a moment; and then his eyes darkened with a frown, as it turned, in its aversion, elsewhere.

‘Humph!’ said Mr. Quinion, looking at us both, I thought. ‘Fine weather!’

Silence ensued, and I was considering how I could best disengage my shoulder from his hand, and go away, when he said:

‘I suppose you are a pretty sharp fellow still? Eh, Brooks?’

‘Aye! He is sharp enough,’ said Mr. Murdstone, impatiently. ‘You had better let him go. He will not thank you for troubling him.’

On this hint, Mr. Quinion released me, and I made the best of my way home. Looking back as I turned into the front garden, I saw Mr. Murdstone leaning against the wicket of the churchyard, and Mr. Quinion talking to him. They were both looking after me, and I felt that they were speaking of me.

Mr. Quinion lay at our house that night. After breakfast, the next morning, I had put my chair away, and was going out of the room, when Mr. Murdstone called me back. He then gravely repaired to another table, where his sister sat herself at her desk. Mr. Quinion, with his hands in his pockets, stood looking out of window; and I stood looking at them all.

‘David,’ said Mr. Murdstone, ‘to the young this is a world for action; not for moping and droning in.’

- ‘As you do,’ added his sister.

‘Jane Murdstone, leave it to me, if you please. I say, David, to the young this is a world for action, and not for moping and droning in. It is especially so for a young boy of your disposition, which requires a great deal of correcting; and to which no greater service can be done than to force it to conform to the ways of the working world, and to bend it and break it.’

‘For stubbornness won’t do here,’ said his sister ‘What it wants is, to be crushed. And crushed it must be. Shall be, too!’

He gave her a look, half in remonstrance, half in approval, and went on:

‘I suppose you know, David, that I am not rich. At any rate, you know it now. You have received some considerable education already. Education is costly; and even if it were not, and I could afford it, I am of opinion that it would not be at all advantageous to you to be kept at school. What is before you, is a fight with the world; and the sooner you begin it, the better.’

I think it occurred to me that I had already begun it, in my poor way: but it occurs to me now, whether or no.

‘You have heard the “counting-house” mentioned sometimes,’ said Mr. Murdstone.

‘The counting-house, sir?’ I repeated. ‘Of Murdstone and Grinby, in the wine trade,’ he replied.

I suppose I looked uncertain, for he went on hastily:

‘You have heard the “counting-house” mentioned, or the business, or the cellars, or the wharf, or something about it.’

‘I think I have heard the business mentioned, sir,’ I said, remembering what I vaguely knew of his and his sister’s resources. ‘But I don’t know when.’

‘It does not matter when,’ he returned. ‘Mr. Quinion manages that business.’

I glanced at the latter deferentially as he stood looking out of window.

‘Mr. Quinion suggests that it gives employment to some other boys, and that he sees no reason why it shouldn’t, on the same terms, give employment to you.’

‘He having,’ Mr. Quinion observed in a low voice, and half turning round, ‘no other prospect, Murdstone.’

Mr. Murdstone, with an impatient, even an angry gesture, resumed, without noticing what he had said:

‘Those terms are, that you will earn enough for yourself to provide for your eating and drinking, and pocket-money. Your lodging (which I have arranged for) will be paid by me. So will your washing -‘

‘- Which will be kept down to my estimate,’ said his sister.

‘Your clothes will be looked after for you, too,’ said Mr. Murdstone; ‘as you will not be able, yet awhile, to get them for yourself. So you are now going to London, David, with Mr. Quinion, to begin the world on your own account.’

‘In short, you are provided for,’ observed his sister; ‘and will please to do your duty.’

Though I quite understood that the purpose of this announcement was to get rid of me, I have no distinct remembrance whether it pleased or frightened me. My impression is, that I was in a state of confusion about it, and, oscillating between the two points, touched neither. Nor had I much time for the clearing of my thoughts, as Mr. Quinion was to go upon the morrow.

Behold me, on the morrow, in a much-worn little white hat, with a black crape round it for my mother, a black jacket, and a pair of hard, stiff corduroy trousers - which Miss Murdstone considered the best armour for the legs in that fight with the world which was now to come off. Behold me so attired, and with my little worldly all before me in a small trunk, sitting, a lone lorn child (as Mrs. Gummidge might have said), in the post-chaise that was carrying Mr. Quinion to the London coach at Yarmouth! See, how our house and church are lessening in the distance; how the grave beneath the tree is blotted out by intervening objects; how the spire points upwards from my old playground no more, and the sky is empty!

CHAPTER 11 I BEGIN LIFE ON MY OWN ACCOUNT, AND DON’T LIKE IT

I know enough of the world now, to have almost lost the capacity of being much surprised by anything; but it is matter of some surprise to me, even now, that I can have been so easily thrown away at such an age. A child of excellent abilities, and with strong powers of observation, quick, eager, delicate, and soon hurt bodily or mentally, it seems wonderful to me that nobody should have made any sign in my behalf. But none was made; and I became, at ten years old, a little labouring hind in the service of Murdstone and Grinby.

Murdstone and Grinby’s warehouse was at the waterside. It was down in Blackfriars. Modern improvements have altered the place; but it was the last house at the bottom of a narrow street, curving down hill to the river, with some stairs at the end, where people took boat. It was a crazy old house with a wharf of its own, abutting on the water when the tide was in, and on the mud when the tide was out, and literally overrun with rats. Its panelled rooms, discoloured with the dirt and smoke of a hundred years, I dare say; its decaying floors and staircase; the squeaking and scuffling of the old grey rats down in the cellars; and the dirt and rottenness of the place; are things, not of many years ago, in my mind, but of the present instant. They are all before me, just as they were in the evil hour when I went among them for the first time, with my trembling hand in Mr. Quinion’s.

Murdstone and Grinby’s trade was among a good many kinds of people, but an important branch of it was the supply of wines and spirits to certain packet ships. I forget now where they chiefly went, but I think there were some among them that made voyages both to the East and West Indies. I know that a great many empty bottles were one of the consequences of this traffic, and that certain men and boys were employed to examine them against the light, and reject those that were flawed, and to rinse and wash them. When the empty bottles ran short, there were labels to be pasted on full ones, or corks to be fitted to them, or seals to be put upon the corks, or finished bottles to be packed in casks. All this work was my work, and of the boys employed upon it I was one.

There were three or four of us, counting me. My working place was established in a corner of the warehouse, where Mr. Quinion could see me, when he chose to stand up on the bottom rail of his stool in the counting-house, and look at me through a window above the desk. Hither, on the first morning of my so auspiciously beginning life on my own account, the oldest of the regular boys was summoned to show me my business. His name was Mick Walker, and he wore a ragged apron and a paper

Comments (0)