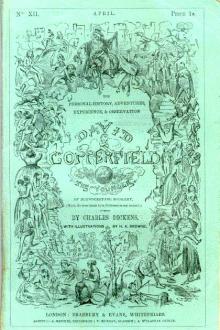

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (sites to read books for free txt) 📕

I need say nothing here, on the first head, because nothing can show better than my history whether that prediction was verified or falsified by the result. On the second branch of the question, I will only remark, that unless I ran through that part of my inheritance while I was still a baby, I have not come into it yet. But I do not at all complain of having been kept out of this property; and if anybody else should be in the present enjoyment of it, he is heartily welcome to keep it.

I was born with a caul, which was advertised for sale, in the newspapers, at the low price of fifteen guineas. Whether sea-going people were short of money about that time, or were short of faith and preferred cork jackets, I don't know; all I know is, that there was but one solitary bidding, and that was from an attorney connected with the bill-broking business, who offered two pounds in cash, and the balance in sherry, but declined to be guaranteed from drowning on any hig

Read free book «David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (sites to read books for free txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: 0679783415

Read book online «David Copperfield by Charles Dickens (sites to read books for free txt) 📕». Author - Charles Dickens

I was soon within sight of Mr. Peggotty’s house, and of the light within it shining through the window. A little floundering across the sand, which was heavy, brought me to the door, and I went in.

It looked very comfortable indeed. Mr. Peggotty had smoked his evening pipe and there were preparations for some supper by and by. The fire was bright, the ashes were thrown up, the locker was ready for little Emily in her old place. In her own old place sat Peggotty, once more, looking (but for her dress) as if she had never left it. She had fallen back, already, on the society of the work-box with St. Paul’s upon the lid, the yard-measure in the cottage, and the bit of wax-candle; and there they all were, just as if they had never been disturbed. Mrs. Gummidge appeared to be fretting a little, in her old corner; and consequently looked quite natural, too.

‘You’re first of the lot, Mas’r Davy!’ said Mr. Peggotty with a happy face. ‘Doen’t keep in that coat, sir, if it’s wet.’

‘Thank you, Mr. Peggotty,’ said I, giving him my outer coat to hang up. ‘It’s quite dry.’

‘So ‘tis!’ said Mr. Peggotty, feeling my shoulders. ‘As a chip! Sit ye down, sir. It ain’t o’ no use saying welcome to you, but you’re welcome, kind and hearty.’

‘Thank you, Mr. Peggotty, I am sure of that. Well, Peggotty!’ said I, giving her a kiss. ‘And how are you, old woman?’

‘Ha, ha!’ laughed Mr. Peggotty, sitting down beside us, and rubbing his hands in his sense of relief from recent trouble, and in the genuine heartiness of his nature; ‘there’s not a woman in the wureld, sir - as I tell her - that need to feel more easy in her mind than her! She done her dooty by the departed, and the departed know’d it; and the departed done what was right by her, as she done what was right by the departed; - and - and - and it’s all right!’

Mrs. Gummidge groaned.

‘Cheer up, my pritty mawther!’ said Mr. Peggotty. (But he shook his head aside at us, evidently sensible of the tendency of the late occurrences to recall the memory of the old one.) ‘Doen’t be down! Cheer up, for your own self, on’y a little bit, and see if a good deal more doen’t come nat’ral!’

‘Not to me, Dan’l,’ returned Mrs. Gummidge. ‘Nothink’s nat’ral to me but to be lone and lorn.’

‘No, no,’ said Mr. Peggotty, soothing her sorrows.

‘Yes, yes, Dan’l!’ said Mrs. Gummidge. ‘I ain’t a person to live with them as has had money left. Thinks go too contrary with me. I had better be a riddance.’

‘Why, how should I ever spend it without you?’ said Mr. Peggotty, with an air of serious remonstrance. ‘What are you a talking on? Doen’t I want you more now, than ever I did?’

‘I know’d I was never wanted before!’ cried Mrs. Gummidge, with a pitiable whimper, ‘and now I’m told so! How could I expect to be wanted, being so lone and lorn, and so contrary!’

Mr. Peggotty seemed very much shocked at himself for having made a speech capable of this unfeeling construction, but was prevented from replying, by Peggotty’s pulling his sleeve, and shaking her head. After looking at Mrs. Gummidge for some moments, in sore distress of mind, he glanced at the Dutch clock, rose, snuffed the candle, and put it in the window.

‘Theer!‘said Mr. Peggotty, cheerily.‘Theer we are, Missis Gummidge!’ Mrs. Gummidge slightly groaned. ‘Lighted up, accordin’ to custom! You’re a wonderin’ what that’s fur, sir! Well, it’s fur our little Em’ly. You see, the path ain’t over light or cheerful arter dark; and when I’m here at the hour as she’s a comin’ home, I puts the light in the winder. That, you see,’ said Mr. Peggotty, bending over me with great glee, ‘meets two objects. She says, says Em’ly, “Theer’s home!” she says. And likewise, says Em’ly, “My uncle’s theer!” Fur if I ain’t theer, I never have no light showed.’

‘You’re a baby!’ said Peggotty; very fond of him for it, if she thought so.

‘Well,’ returned Mr. Peggotty, standing with his legs pretty wide apart, and rubbing his hands up and down them in his comfortable satisfaction, as he looked alternately at us and at the fire. ‘I doen’t know but I am. Not, you see, to look at.’

‘Not azackly,’ observed Peggotty.

‘No,’ laughed Mr. Peggotty, ‘not to look at, but to - to consider on, you know. I doen’t care, bless you! Now I tell you. When I go a looking and looking about that theer pritty house of our Em’ly’s, I’m - I’m Gormed,’ said Mr. Peggotty, with sudden emphasis - ‘theer! I can’t say more - if I doen’t feel as if the littlest things was her, a’most. I takes ‘em up and I put ‘em down, and I touches of ‘em as delicate as if they was our Em’ly. So ‘tis with her little bonnets and that. I couldn’t see one on ‘em rough used a purpose - not fur the whole wureld. There’s a babby fur you, in the form of a great Sea Porkypine!’ said Mr. Peggotty, relieving his earnestness with a roar of laughter.

Peggotty and I both laughed, but not so loud.

‘It’s my opinion, you see,’ said Mr. Peggotty, with a delighted face, after some further rubbing of his legs, ‘as this is along of my havin’ played with her so much, and made believe as we was Turks, and French, and sharks, and every wariety of forinners - bless you, yes; and lions and whales, and I doen’t know what all! - when she warn’t no higher than my knee. I’ve got into the way on it, you know. Why, this here candle, now!’ said Mr. Peggotty, gleefully holding out his hand towards it, ‘I know wery well that arter she’s married and gone, I shall put that candle theer, just the same as now. I know wery well that when I’m here o’ nights (and where else should I live, bless your arts, whatever fortun’ I come into!) and she ain’t here or I ain’t theer, I shall put the candle in the winder, and sit afore the fire, pretending I’m expecting of her, like I’m a doing now. THERE’S a babby for you,’ said Mr. Peggotty, with another roar, ‘in the form of a Sea Porkypine! Why, at the present minute, when I see the candle sparkle up, I says to myself, “She’s a looking at it! Em’ly’s a coming!” THERE’S a babby for you, in the form of a Sea Porkypine! Right for all that,’ said Mr. Peggotty, stopping in his roar, and smiting his hands together; ‘fur here she is!’

It was only Ham. The night should have turned more wet since I came in, for he had a large sou’wester hat on, slouched over his face.

‘Wheer’s Em’ly?’ said Mr. Peggotty.

Ham made a motion with his head, as if she were outside. Mr. Peggotty took the light from the window, trimmed it, put it on the table, and was busily stirring the fire, when Ham, who had not moved, said:

‘Mas’r Davy, will you come out a minute, and see what Em’ly and me has got to show you?’

We went out. As I passed him at the door, I saw, to my astonishment and fright, that he was deadly pale. He pushed me hastily into the open air, and closed the door upon us. Only upon us two.

‘Ham! what’s the matter?’

‘Mas’r Davy! -‘ Oh, for his broken heart, how dreadfully he wept!

I was paralysed by the sight of such grief. I don’t know what I thought, or what I dreaded. I could only look at him.

‘Ham! Poor good fellow! For Heaven’s sake, tell me what’s the matter!’

‘My love, Mas’r Davy - the pride and hope of my art - her that I’d have died for, and would die for now - she’s gone!’

‘Gone!’

‘Em’ly’s run away! Oh, Mas’r Davy, think HOW she’s run away, when I pray my good and gracious God to kill her (her that is so dear above all things) sooner than let her come to ruin and disgrace!’

The face he turned up to the troubled sky, the quivering of his clasped hands, the agony of his figure, remain associated with the lonely waste, in my remembrance, to this hour. It is always night there, and he is the only object in the scene.

‘You’re a scholar,’ he said, hurriedly, ‘and know what’s right and best. What am I to say, indoors? How am I ever to break it to him, Mas’r Davy?’

I saw the door move, and instinctively tried to hold the latch on the outside, to gain a moment’s time. It was too late. Mr. Peggotty thrust forth his face; and never could I forget the change that came upon it when he saw us, if I were to live five hundred years.

I remember a great wail and cry, and the women hanging about him, and we all standing in the room; I with a paper in my hand, which Ham had given me; Mr. Peggotty, with his vest torn open, his hair wild, his face and lips quite white, and blood trickling down his bosom (it had sprung from his mouth, I think), looking fixedly at me.

‘Read it, sir,’ he said, in a low shivering voice. ‘Slow, please. I doen’t know as I can understand.’

In the midst of the silence of death, I read thus, from a blotted letter:

‘“When you, who love me so much better than I ever have deserved, even when my mind was innocent, see this, I shall be far away.”’

‘I shall be fur away,’ he repeated slowly. ‘Stop! Em’ly fur away. Well!’

‘“When I leave my dear home - my dear home - oh, my dear home! - in the morning,”’

the letter bore date on the previous night:

’”- it will be never to come back, unless he brings me back a lady. This will be found at night, many hours after, instead of me. Oh, if you knew how my heart is torn. If even you, that I have wronged so much, that never can forgive me, could only know what I suffer! I am too wicked to write about myself! Oh, take comfort in thinking that I am so bad. Oh, for mercy’s sake, tell uncle that I never loved him half so dear as now. Oh, don’t remember how affectionate and kind you have all been to me - don’t remember we were ever to be married - but try to think as if I died when I was little, and was buried somewhere. Pray Heaven that I am going away from, have compassion on my uncle! Tell him that I never loved him half so dear. Be his comfort. Love some good girl that will be what I was once to uncle, and be true to you, and worthy of you, and know no shame but me. God bless all! I’ll pray for all, often, on my knees. If he don’t bring me back a lady, and I don’t pray for my own self, I’ll pray for all. My parting love to uncle. My last tears, and my last thanks, for uncle!”’

That was all.

He stood, long after I had ceased to read, still looking at me. At length I ventured to take his hand, and to entreat him, as well as I could, to

Comments (0)