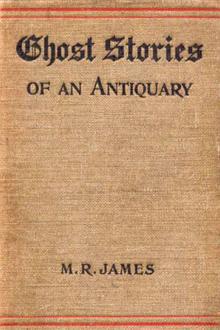

Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by Montague Rhodes James (large screen ebook reader txt) 📕

'Is it possible that you found a body?' said the visitor, with an odd feeling of nervousness.

'We did that: but what's more, in every sense of the word, we found two.'

'Good Heavens! Two? Was there anything to show how they got there? Was this thing found with them?'

'It was. Amongst the rags of the clothes that were on one of the bodies. A bad business, whatever the story of it may have been. One body had the arms tight round the other. They must have been there thirty years or more--long enough before we came to this place. You may judge we filled the well up fast enough. Do you make anything of what's cut o

Read free book «Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by Montague Rhodes James (large screen ebook reader txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Montague Rhodes James

- Performer: -

Read book online «Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by Montague Rhodes James (large screen ebook reader txt) 📕». Author - Montague Rhodes James

not guilty?

Pris. My lord, I would humbly offer this to the court. If I plead now,

shall I have an opportunity after to except against the indictment?

L.C.J. Yes, yes, that comes after verdict: that will be saved to you,

and counsel assigned if there be matter of law, but that which you have

now to do is to plead.

Then after some little parleying with the court (which seemed strange

upon such a plain indictment) the prisoner pleaded Not Guilty.

Cl. of Ct. Cul-prit. How wilt thou be tried?

Pris. By God and my country.

Cl. of Ct. God send thee a good deliverance.

L.C.J. Why, how is this? Here has been a great to-do that you should

not be tried at Exeter by your country, but be brought here to London,

and now you ask to be tried by your country. Must we send you to Exeter

again?

Pris. My lord, I understood it was the form.

L.C.J. So it is, man: we spoke only in the way of pleasantness. Well,

go on and swear the jury.

So they were sworn. I omit the names. There was no challenging on the

prisoner’s part, for, as he said, he did not know any of the persons

called. Thereupon the prisoner asked for the use of pen, ink, and paper,

to which the L. C. J. replied: ‘Ay, ay, in God’s name let him have it.’

Then the usual charge was delivered to the jury, and the case opened by

the junior counsel for the King, Mr Dolben.

The Attorney-General followed:

May it please your lordship, and you gentlemen of the jury, I am of

counsel for the King against the prisoner at the bar. You have heard that

he stands indicted for a murder done upon the person of a young girl.

Such crimes as this you may perhaps reckon to be not uncommon, and,

indeed, in these times, I am sorry to say it, there is scarce any fact so

barbarous and unnatural but what we may hear almost daily instances of

it. But I must confess that in this murder that is charged upon the

prisoner there are some particular features that mark it out to be such

as I hope has but seldom if ever been perpetrated upon English ground.

For as we shall make it appear, the person murdered was a poor country

girl (whereas the prisoner is a gentleman of a proper estate) and,

besides that, was one to whom Providence had not given the full use of

her intellects, but was what is termed among us commonly an innocent or

natural: such an one, therefore, as one would have supposed a gentleman

of the prisoner’s quality more likely to overlook, or, if he did notice

her, to be moved to compassion for her unhappy condition, than to lift up

his hand against her in the very horrid and barbarous manner which we

shall show you he used.

Now to begin at the beginning and open the matter to you orderly: About

Christmas of last year, that is the year 1683, this gentleman, Mr Martin,

having newly come back into his own country from the University of

Cambridge, some of his neighbours, to show him what civility they could

(for his family is one that stands in very good repute all over that

country), entertained him here and there at their Christmas merrymakings,

so that he was constantly riding to and fro, from one house to another,

and sometimes, when the place of his destination was distant, or for

other reason, as the unsafeness of the roads, he would be constrained to

lie the night at an inn. In this way it happened that he came, a day or

two after the Christmas, to the place where this young girl lived with

her parents, and put up at the inn there, called the New Inn, which is,

as I am informed, a house of good repute. Here was some dancing going on

among the people of the place, and Ann Clark had been brought in, it

seems, by her elder sister to look on; but being, as I have said, of weak

understanding, and, besides that, very uncomely in her appearance, it was

not likely she should take much part in the merriment; and accordingly

was but standing by in a corner of the room. The prisoner at the bar,

seeing her, one must suppose by way of a jest, asked her would she dance

with him. And in spite of what her sister and others could say to prevent

it and to dissuade her—

L.C.J. Come, Mr Attorney, we are not set here to listen to tales of

Christmas parties in taverns. I would not interrupt you, but sure you

have more weighty matters than this. You will be telling us next what

tune they danced to.

Att. My lord, I would not take up the time of the court with what is

not material: but we reckon it to be material to show how this unlikely

acquaintance begun: and as for the tune, I believe, indeed, our evidence

will show that even that hath a bearing on the matter in hand.

L.C.J. Go on, go on, in God’s name: but give us nothing that is

impertinent.

Att. Indeed, my lord, I will keep to my matter. But, gentlemen, having

now shown you, as I think, enough of this first meeting between the

murdered person and the prisoner, I will shorten my tale so far as to say

that from then on there were frequent meetings of the two: for the young

woman was greatly tickled with having got hold (as she conceived it) of

so likely a sweetheart, and he being once a week at least in the habit of

passing through the street where she lived, she would be always on the

watch for him; and it seems they had a signal arranged: he should whistle

the tune that was played at the tavern: it is a tune, as I am informed,

well known in that country, and has a burden, ‘_Madam, will you walk,

will you talk with me?_’

L.C.J. Ay, I remember it in my own country, in Shropshire. It runs

somehow thus, doth it not? [Here his lordship whistled a part of a tune,

which was very observable, and seemed below the dignity of the court. And

it appears he felt it so himself, for he said:] But this is by the mark,

and I doubt it is the first time we have had dance-tunes in this court.

The most part of the dancing we give occasion for is done at Tyburn.

[Looking at the prisoner, who appeared very much disordered.] You said

the tune was material to your case, Mr Attorney, and upon my life I think

Mr Martin agrees with you. What ails you, man? staring like a player that

sees a ghost!

Pris. My lord, I was amazed at hearing such trivial, foolish things as

they bring against me.

L.C.J. Well, well, it lies upon Mr Attorney to show whether they be

trivial or not: but I must say, if he has nothing worse than this he has

said, you have no great cause to be in amaze. Doth it not lie something

deeper? But go on, Mr Attorney.

Att. My lord and gentlemen—all that I have said so far you may indeed

very reasonably reckon as having an appearance of triviality. And, to be

sure, had the matter gone no further than the humouring of a poor silly

girl by a young gentleman of quality, it had been very well. But to

proceed. We shall make it appear that after three or four weeks the

prisoner became contracted to a young gentlewoman of that country, one

suitable every way to his own condition, and such an arrangement was on

foot that seemed to promise him a happy and a reputable living. But

within no very long time it seems that this young gentlewoman, hearing of

the jest that was going about that countryside with regard to the

prisoner and Ann Clark, conceived that it was not only an unworthy

carriage on the part of her lover, but a derogation to herself that he

should suffer his name to be sport for tavern company: and so without

more ado she, with the consent of her parents, signified to the prisoner

that the match between them was at an end. We shall show you that upon

the receipt of this intelligence the prisoner was greatly enraged against

Ann Clark as being the cause of his misfortune (though indeed there was

nobody answerable for it but himself), and that he made use of many

outrageous expressions and threatenings against her, and subsequently

upon meeting with her both abused her and struck at her with his whip:

but she, being but a poor innocent, could not be persuaded to desist from

her attachment to him, but would often run after him testifying with

gestures and broken words the affection she had to him: until she was

become, as he said, the very plague of his life. Yet, being that affairs

in which he was now engaged necessarily took him by the house in which

she lived, he could not (as I am willing to believe he would otherwise

have done) avoid meeting with her from time to time. We shall further

show you that this was the posture of things up to the 15th day of May in

this present year. Upon that day the prisoner comes riding through the

village, as of custom, and met with the young woman: but in place of

passing her by, as he had lately done, he stopped, and said some words to

her with which she appeared wonderfully pleased, and so left her; and

after that day she was nowhere to be found, notwithstanding a strict

search was made for her. The next time of the prisoner’s passing through

the place, her relations inquired of him whether he should know anything

of her whereabouts; which he totally denied. They expressed to him their

fears lest her weak intellects should have been upset by the attention he

had showed her, and so she might have committed some rash act against her

own life, calling him to witness the same time how often they had

beseeched him to desist from taking notice of her, as fearing trouble

might come of it: but this, too, he easily laughed away. But in spite of

this light behaviour, it was noticeable in him that about this time his

carriage and demeanour changed, and it was said of him that he seemed a

troubled man. And here I come to a passage to which I should not dare to

ask your attention, but that it appears to me to be founded in truth, and

is supported by testimony deserving of credit. And, gentlemen, to my

judgement it doth afford a great instance of God’s revenge against

murder, and that He will require the blood of the innocent.

[Here Mr Attorney made a pause, and shifted with his papers: and it was

thought remarkable by me and others, because he was a man not easily

dashed.]

L.C.J. Well, Mr Attorney, what is your instance?

Att. My lord, it is a strange one, and the truth is that, of all the

cases I have been concerned in, I cannot call to mind the like of it. But

to be short, gentlemen, we shall bring you testimony that Ann Clark was

seen after this 15th of May, and that, at such time as she was so seen,

it

Comments (0)