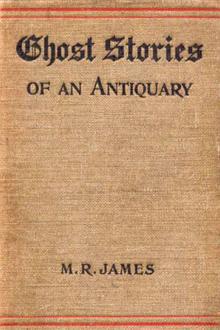

Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by Montague Rhodes James (large screen ebook reader txt) 📕

'Is it possible that you found a body?' said the visitor, with an odd feeling of nervousness.

'We did that: but what's more, in every sense of the word, we found two.'

'Good Heavens! Two? Was there anything to show how they got there? Was this thing found with them?'

'It was. Amongst the rags of the clothes that were on one of the bodies. A bad business, whatever the story of it may have been. One body had the arms tight round the other. They must have been there thirty years or more--long enough before we came to this place. You may judge we filled the well up fast enough. Do you make anything of what's cut o

Read free book «Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by Montague Rhodes James (large screen ebook reader txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Montague Rhodes James

- Performer: -

Read book online «Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by Montague Rhodes James (large screen ebook reader txt) 📕». Author - Montague Rhodes James

they passed the park gates, and with the lodge-keeper himself, who was

attending to the park road. I cannot, however, spare the time to report

the progress fully. As they traversed the half-mile or so between the

lodge and the house, Humphreys took occasion to ask his companion some

question which brought up the topic of his late uncle, and it did not

take long before Mr Cooper was embarked upon a disquisition.

‘It is singular to think, as the wife was saying just now, that you

should never have seen the old gentleman. And yet—you won’t

misunderstand me, Mr Humphreys, I feel confident, when I say that in my

opinion there would have been but little congeniality betwixt yourself

and him. Not that I have a word to say in deprecation—not a single word.

I can tell you what he was,’ said Mr Cooper, pulling up suddenly and

fixing Humphreys with his eye. ‘Can tell you what he was in a nutshell,

as the saying goes. He was a complete, thorough valentudinarian. That

describes him to a T. That’s what he was, sir, a complete

valentudinarian. No participation in what went on around him. I did

venture, I think, to send you a few words of cutting from our local

paper, which I took the occasion to contribute on his decease. If I

recollect myself aright, such is very much the gist of them. But don’t,

Mr Humphreys,’ continued Cooper, tapping him impressively on the

chest,—‘don’t you run away with the impression that I wish to say aught

but what is most creditable—_most_ creditable—of your respected uncle

and my late employer. Upright, Mr Humphreys—open as the day; liberal to

all in his dealings. He had the heart to feel and the hand to

accommodate. But there it was: there was the stumbling-block—his

unfortunate health—or, as I might more truly phrase it, his want of

health.’

‘Yes, poor man. Did he suffer from any special disorder before his last

illness—which, I take it, was little more than old age?’

‘Just that, Mr Humphreys—just that. The flash flickering slowly away in

the pan,’ said Cooper, with what he considered an appropriate

gesture,—‘the golden bowl gradually ceasing to vibrate. But as to your

other question I should return a negative answer. General absence of

vitality? yes: special complaint? no, unless you reckon a nasty cough he

had with him. Why, here we are pretty much at the house. A handsome

mansion, Mr Humphreys, don’t you consider?’

It deserved the epithet, on the whole: but it was oddly proportioned—a

very tall red-brick house, with a plain parapet concealing the roof

almost entirely. It gave the impression of a town house set down in the

country; there was a basement, and a rather imposing flight of steps

leading up to the front door. It seemed also, owing to its height, to

desiderate wings, but there were none. The stables and other offices were

concealed by trees. Humphreys guessed its probable date as 1770 or

thereabouts.

The mature couple who had been engaged to act as butler and

cook-housekeeper were waiting inside the front door, and opened it as

their new master approached. Their name, Humphreys already knew, was

Calton; of their appearance and manner he formed a favourable impression

in the few minutes’ talk he had with them. It was agreed that he should

go through the plate and the cellar next day with Mr Calton, and that Mrs

C. should have a talk with him about linen, bedding, and so on—what

there was, and what there ought to be. Then he and Cooper, dismissing the

Caltons for the present, began their view of the house. Its topography is

not of importance to this story. The large rooms on the ground floor were

satisfactory, especially the library, which was as large as the

dining-room, and had three tall windows facing east. The bedroom prepared

for Humphreys was immediately above it. There were many pleasant, and a

few really interesting, old pictures. None of the furniture was new, and

hardly any of the books were later than the seventies. After hearing of

and seeing the few changes his uncle had made in the house, and

contemplating a shiny portrait of him which adorned the drawing-room,

Humphreys was forced to agree with Cooper that in all probability there

would have been little to attract him in his predecessor. It made him

rather sad that he could not be sorry—_dolebat se dolere non posse_—for

the man who, whether with or without some feeling of kindliness towards

his unknown nephew, had contributed so much to his well-being; for he

felt that Wilsthorpe was a place in which he could be happy, and

especially happy, it might be, in its library.

And now it was time to go over the garden: the empty stables could wait,

and so could the laundry. So to the garden they addressed themselves, and

it was soon evident that Miss Cooper had been right in thinking that

there were possibilities. Also that Mr Cooper had done well in keeping on

the gardener. The deceased Mr Wilson might not have, indeed plainly had

not, been imbued with the latest views on gardening, but whatever had

been done here had been done under the eye of a knowledgeable man, and

the equipment and stock were excellent. Cooper was delighted with the

pleasure Humphreys showed, and with the suggestions he let fall from time

to time. ‘I can see,’ he said, ‘that you’ve found your meatear here, Mr

Humphreys: you’ll make this place a regular signosier before very many

seasons have passed over our heads. I wish Clutterham had been

here—that’s the head gardener—and here he would have been of course,

as I told you, but for his son’s being horse doover with a fever, poor

fellow! I should like him to have heard how the place strikes you.’

‘Yes, you told me he couldn’t be here today, and I was very sorry to hear

the reason, but it will be time enough tomorrow. What is that white

building on the mound at the end of the grass ride? Is it the temple Miss

Cooper mentioned?’

‘That it is, Mr Humphreys—the Temple of Friendship. Constructed of

marble brought out of Italy for the purpose, by your late uncle’s

grandfather. Would it interest you perhaps to take a turn there? You get

a very sweet prospect of the park.’

The general lines of the temple were those of the Sibyl’s Temple at

Tivoli, helped out by a dome, only the whole was a good deal smaller.

Some ancient sepulchral reliefs were built into the wall, and about it

all was a pleasant flavour of the grand tour. Cooper produced the key,

and with some difficulty opened the heavy door. Inside there was a

handsome ceiling, but little furniture. Most of the floor was occupied by

a pile of thick circular blocks of stone, each of which had a single

letter deeply cut on its slightly convex upper surface. ‘What is the

meaning of these?’ Humphreys inquired.

‘Meaning? Well, all things, we’re told, have their purpose, Mr Humphreys,

and I suppose these blocks have had theirs as well as another. But what

that purpose is or was [Mr Cooper assumed a didactic attitude here], I,

for one, should be at a loss to point out to you, sir. All I know of

them—and it’s summed up in a very few words—is just this: that they’re

stated to have been removed by your late uncle, at a period before I

entered on the scene, from the maze. That, Mr Humphreys, is—’

‘Oh, the maze!’ exclaimed Humphreys. ‘I’d forgotten that: we must have a

look at it. Where is it?’

Cooper drew him to the door of the temple, and pointed with his stick.

‘Guide your eye,’ he said (somewhat in the manner of the Second Elder in

Handel’s ‘Susanna’—

Far to the west direct your straining eyes

Where yon tall holm-tree rises to the skies)

‘Guide your eye by my stick here, and follow out the line directly

opposite to the spot where we’re standing now, and I’ll engage, Mr

Humphreys, that you’ll catch the archway over the entrance. You’ll see it

just at the end of the walk answering to the one that leads up to this

very building. Did you think of going there at once? because if that be

the case, I must go to the house and procure the key. If you would walk

on there, I’ll rejoin you in a few moments’ time.’

Accordingly Humphreys strolled down the ride leading to the temple, past

the garden-front of the house, and up the turfy approach to the archway

which Cooper had pointed out to him. He was surprised to find that the

whole maze was surrounded by a high wall, and that the archway was

provided with a padlocked iron gate; but then he remembered that Miss

Cooper had spoken of his uncle’s objection to letting anyone enter this

part of the garden. He was now at the gate, and still Cooper came not.

For a few minutes he occupied himself in reading the motto cut over the

entrance, Secretum meum mihi et filiis domus meae, and in trying to

recollect the source of it. Then he became impatient and considered the

possibility of scaling the wall. This was clearly not worth while; it

might have been done if he had been wearing an older suit: or could the

padlock—a very old one—be forced? No, apparently not: and yet, as he

gave a final irritated kick at the gate, something gave way, and the lock

fell at his feet. He pushed the gate open inconveniencing a number of

nettles as he did so, and stepped into the enclosure.

It was a yew maze, of circular form, and the hedges, long untrimmed, had

grown out and upwards to a most unorthodox breadth and height. The walks,

too, were next door to impassable. Only by entirely disregarding

scratches, nettle-stings, and wet, could Humphreys force his way along

them; but at any rate this condition of things, he reflected, would make

it easier for him to find his way out again, for he left a very visible

track. So far as he could remember, he had never been in a maze before,

nor did it seem to him now that he had missed much. The dankness and

darkness, and smell of crushed goosegrass and nettles were anything but

cheerful. Still, it did not seem to be a very intricate specimen of its

kind. Here he was (by the way, was that Cooper arrived at last? No!) very

nearly at the heart of it, without having taken much thought as to what

path he was following. Ah! there at last was the centre, easily gained.

And there was something to reward him. His first impression was that the

central ornament was a sundial; but when he had switched away some

portion of the thick growth of brambles and bindweed that had formed over

it, he saw that it was a less ordinary decoration. A stone column about

four feet high, and on the top of it a metal globe—copper, to judge by

the green patina—engraved, and finely engraved too, with figures in

outline, and letters. That was what Humphreys saw, and a brief glance at

the figures convinced him that it was one of those mysterious things

called celestial globes, from which, one would suppose, no one ever yet

derived any information about the heavens. However, it was too dark—at

least in the maze—for him to examine this curiosity at all closely, and

besides, he now heard Cooper’s voice, and sounds as of an elephant in the

jungle. Humphreys called to him to follow the track he had beaten out,

and soon Cooper

Comments (0)