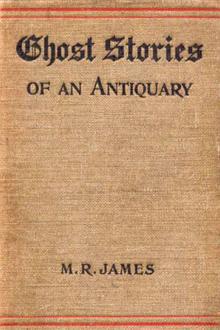

Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by Montague Rhodes James (large screen ebook reader txt) 📕

'Is it possible that you found a body?' said the visitor, with an odd feeling of nervousness.

'We did that: but what's more, in every sense of the word, we found two.'

'Good Heavens! Two? Was there anything to show how they got there? Was this thing found with them?'

'It was. Amongst the rags of the clothes that were on one of the bodies. A bad business, whatever the story of it may have been. One body had the arms tight round the other. They must have been there thirty years or more--long enough before we came to this place. You may judge we filled the well up fast enough. Do you make anything of what's cut o

Read free book «Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by Montague Rhodes James (large screen ebook reader txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Montague Rhodes James

- Performer: -

Read book online «Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by Montague Rhodes James (large screen ebook reader txt) 📕». Author - Montague Rhodes James

you were about: for, for all I have brought back the Jewel (which he

shew’d them, and ‘twas indeed a rare Piece) I have brought back that with

it that will leave me neither Rest at Night nor Pleasure by Day.”

Whereupon they were instant with him to learn his Meaning, and where his

Company should be that went so sore against his Stomach. “O” says he

“‘tis here in my Breast: I cannot flee from it, do what I may.” So it

needed no Wizard to help them to a guess that it was the Recollection of

what he had seen that troubled him so wonderfully. But they could get no

more of him for a long Time but by Fits and Starts. However at long and

at last they made shift to collect somewhat of this kind: that at first,

while the Sun was bright, he went merrily on, and without any Difficulty

reached the Heart of the Labyrinth and got the Jewel, and so set out on

his way back rejoycing: but as the Night fell, _wherein all the Beasts of

the Forest do move_, he begun to be sensible of some Creature keeping

Pace with him and, as he thought, peering and looking upon him from the

next Alley to that he was in; and that when he should stop, this

Companion should stop also, which put him in some Disorder of his

Spirits. And, indeed, as the Darkness increas’d, it seemed to him that

there was more than one, and, it might be, even a whole Band of such

Followers: at least so he judg’d by the Rustling and Cracking that they

kept among the Thickets; besides that there would be at a Time a Sound of

Whispering, which seem’d to import a Conference among them. But in regard

of who they were or what Form they were of, he would not be persuaded to

say what he thought. Upon his Hearers asking him what the Cries were

which they heard in the Night (as was observ’d above) he gave them this

Account: That about Midnight (so far as he could judge) he heard his Name

call’d from a long way off, and he would have been sworn it was his

Brother that so call’d him. So he stood still and hilloo’d at the Pitch

of his Voice, and he suppos’d that the Echo, or the Noyse of his

Shouting, disguis’d for the Moment any lesser sound; because, when there

fell a Stillness again, he distinguish’d a Trampling (not loud) of

running Feet coming very close behind him, wherewith he was so daunted

that himself set off to run, and that he continued till the Dawn broke.

Sometimes when his Breath fail’d him, he would cast himself flat on his

Face, and hope that his Pursuers might over-run him in the Darkness, but

at such a Time they would regularly make a Pause, and he could hear them

pant and snuff as it had been a Hound at Fault: which wrought in him so

extream an Horrour of mind, that he would be forc’d to betake himself

again to turning and doubling, if by any Means he might throw them off

the Scent. And, as if this Exertion was in itself not terrible enough, he

had before him the constant Fear of falling into some Pit or Trap, of

which he had heard, and indeed seen with his own Eyes that there were

several, some at the sides and other in the Midst of the Alleys. So that

in fine (he said) a more dreadful Night was never spent by Mortal

Creature than that he had endur’d in that Labyrinth; and not that Jewel

which he had in his Wallet, nor the richest that was ever brought out of

the Indies, could be a sufficient Recompence to him for the Pains he

had suffered.

‘I will spare to set down the further Recital of this Man’s Troubles,

inasmuch as I am confident my Reader’s Intelligence will hit the

Parallel I desire to draw. For is not this Jewel a just Emblem of the

Satisfaction which a Man may bring back with him from a Course of this

World’s Pleasures? and will not the Labyrinth serve for an Image of the

World itself wherein such a Treasure (if we may believe the common Voice)

is stored up?’

At about this point Humphreys thought that a little Patience would be an

agreeable change, and that the writer’s ‘improvement’ of his Parable

might be left to itself. So he put the book back in its former place,

wondering as he did so whether his uncle had ever stumbled across that

passage; and if so, whether it had worked on his fancy so much as to make

him dislike the idea of a maze, and determine to shut up the one in the

garden. Not long afterwards he went to bed.

The next day brought a morning’s hard work with Mr Cooper, who, if

exuberant in language, had the business of the estate at his fingers’

ends. He was very breezy this morning, Mr Cooper was: had not forgotten

the order to clear out the maze—the work was going on at that moment:

his girl was on the tentacles of expectation about it. He also hoped that

Humphreys had slept the sleep of the just, and that we should be favoured

with a continuance of this congenial weather At luncheon he enlarged on

the pictures in the dining-room, and pointed out the portrait of the

constructor of the temple and the maze. Humphreys examined this with

considerable interest. It was the work of an Italian, and had been

painted when old Mr Wilson was visiting Rome as a young man. (There was,

indeed, a view of the Colosseum in the background.) A pale thin face and

large eyes were the characteristic features. In the hand was a partially

unfolded roll of paper, on which could be distinguished the plan of a

circular building, very probably the temple, and also part of that of a

labyrinth. Humphreys got up on a chair to examine it, but it was not

painted with sufficient clearness to be worth copying. It suggested to

him, however, that he might as well make a plan of his own maze and hang

it in the hall for the use of visitors.

This determination of his was confirmed that same afternoon; for when Mrs

and Miss Cooper arrived, eager to be inducted into the maze, he found

that he was wholly unable to lead them to the centre. The gardeners had

removed the guide-marks they had been using, and even Clutterham, when

summoned to assist, was as helpless as the rest. ‘The point is, you see,

Mr Wilson—I should say ‘Umphreys—these mazes is purposely constructed

so much alike, with a view to mislead. Still, if you’ll foller me, I

think I can put you right. I’ll just put my ‘at down ‘ere as a

starting-point.’ He stumped off, and after five minutes brought the party

safe to the hat again. ‘Now that’s a very peculiar thing,’ he said, with

a sheepish laugh. ‘I made sure I’d left that ‘at just over against a

bramble-bush, and you can see for yourself there ain’t no bramble-bush

not in this walk at all. If you’ll allow me, Mr Humphreys—that’s the

name, ain’t it, sir?—I’ll just call one of the men in to mark the place

like.’

William Crack arrived, in answer to repeated shouts. He had some

difficulty in making his way to the party. First he was seen or heard in

an inside alley, then, almost at the same moment, in an outer one.

However, he joined them at last, and was first consulted without effect

and then stationed by the hat, which Clutterham still considered it

necessary to leave on the ground. In spite of this strategy, they spent

the best part of three-quarters of an hour in quite fruitless wanderings,

and Humphreys was obliged at last, seeing how tired Mrs Cooper was

becoming, to suggest a retreat to tea, with profuse apologies to Miss

Cooper. ‘At any rate you’ve won your bet with Miss Foster,’ he said; ‘you

have been inside the maze; and I promise you the first thing I do shall

be to make a proper plan of it with the lines marked out for you to go

by.’ ‘That’s what’s wanted, sir,’ said Clutterham, ‘someone to draw out a

plan and keep it by them. It might be very awkward, you see, anyone

getting into that place and a shower of rain come on, and them not able

to find their way out again; it might be hours before they could be got

out, without you’d permit of me makin’ a short cut to the middle: what my

meanin’ is, takin’ down a couple of trees in each ‘edge in a straight

line so as you could git a clear view right through. Of course that’d do

away with it as a maze, but I don’t know as you’d approve of that.’

‘No, I won’t have that done yet: I’ll make a plan first, and let you have

a copy. Later on, if we find occasion, I’ll think of what you say.’

Humphreys was vexed and ashamed at the fiasco of the afternoon, and could

not be satisfied without making another effort that evening to reach the

centre of the maze. His irritation was increased by finding it without a

single false step. He had thoughts of beginning his plan at once; but the

light was fading, and he felt that by the time he had got the necessary

materials together, work would be impossible.

Next morning accordingly, carrying a drawing-board, pencils, compasses,

cartridge paper, and so forth (some of which had been borrowed from the

Coopers and some found in the library cupboards), he went to the middle

of the maze (again without any hesitation), and set out his materials. He

was, however, delayed in making a start. The brambles and weeds that had

obscured the column and globe were now all cleared away, and it was for

the first time possible to see clearly what these were like. The column

was featureless, resembling those on which sundials are usually placed.

Not so the globe. I have said that it was finely engraved with figures

and inscriptions, and that on a first glance Humphreys had taken it for a

celestial globe: but he soon found that it did not answer to his

recollection of such things. One feature seemed familiar; a winged

serpent—Draco—encircled it about the place which, on a terrestrial

globe, is occupied by the equator: but on the other hand, a good part of

the upper hemisphere was covered by the outspread wings of a large figure

whose head was concealed by a ring at the pole or summit of the whole.

Around the place of the head the words princeps tenebrarum could be

deciphered. In the lower hemisphere there was a space hatched all over

with cross-lines and marked as umbra mortis. Near it was a range of

mountains, and among them a valley with flames rising from it. This was

lettered (will you be surprised to learn it?) vallis filiorum Hinnom.

Above and below Draco were outlined various figures not unlike the

pictures of the ordinary constellations, but not the same. Thus, a nude

man with a raised club was described, not as Hercules but as Cain.

Another, plunged up to his middle in earth and stretching out despairing

arms, was Chore, not Ophiuchus, and a third, hung by his hair to a

snaky tree, was Absolon. Near the last, a man in long robes and high

cap, standing in a

Comments (0)