All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

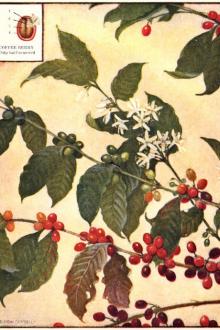

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

The term "steel-cut" is generally understood to mean that in the grinding process the chaff has been removed and an approximate uniformity of granules has been obtained by sifting. The term does not necessarily mean that the grinding mills have steel burrs. In fact, most firms employ burrs made of cast-iron or of a composition metal known as "burr metal", because of its combined hardness and toughness.

The "steel-cut" idea is another of those sophistries for which American advertising methods have been largely responsible in the development of the package-coffee business in the United States. The term "steel-cut" lost all its value as an advertising catchword for the original user when every other dealer began to use it, no matter how the ground coffee was produced. When the public has been taught that coffee should be "steel-cut", it is hard to sell it ground coffee unless it is called "steel-cut"; although a truer education of the consumer would have caused him to insist on buying whole bean coffee to be ground at home.

Smyser Package-Making-and-Filling Machine at the Arbuckle Plant, New York

This machine was invented by Henry E. Smyser of Philadelphia, who secured the first patent in 1880, but it has been much improved by the Arbuckle engineers. The half shown on the left makes the one-pound paper bags complete, including the separate lining of parchment, fills the bag, automatically inserts a premium list at the same time, packs it down, seals it, and delivers it on a short conveyor to the other half (shown on the right) where the package is wrapped in the outside glassine paper and pushed out on a table for the girls to put into shipping cases

"Steel-cut" coffee, that is, a medium-ground coffee with the chaff blown out, does not compare in cup test with coffee that has been more scientifically ground and not given the chaff removal treatment that is largely associated in the public mind with the idea of the steel-cut process.

Five distinct operations are performed by the units comprising this Pneumatic installation, viz., carton-feeding, bottom-sealing, lining, weighing and top-sealing

According to the results of the trade canvass previously referred to, it would appear that the terms most suited to convey the right idea of the different grades of grinding, and likely to be acceptable to the greatest number, would be "coarse" (for boiling, and including all the coarser grades); "medium" (for coffee made in the ordinary pot, including the so-called "steel-cut"); "fine" (like granulated sugar, and used for percolators); "very fine" (like cornmeal, and used for drip or filtration methods); "powdered" (like flour, and used for Turkish coffee).

Coffee begins to lose its strength immediately after roasting, the rate of loss increasing rapidly after grinding. In a test carried out by a Michigan coffee packer,[333] it was discovered that a mixture of a very fine with a coarse grind gives the best results in the cup. It was also determined that coarse ground coffee loses its strength more rapidly than the medium ground; while the latter deteriorates more quickly than a fine ground; and so on, down the scale. His conclusions were that the most satisfactory grind for putting into packages that are likely to stand for some time before being consumed is a mixture consisting of about ninety percent finely ground coffee and ten percent coarse. His theory is that the fine grind supplies sufficiently high body extraction; the coarse, the needful flavor and aroma. On this irregular grind a United States patent (No. 14,520) has been granted, in which the inventor claims that the ninety percent of fine eliminates the interstices—that allow too free ventilation in a coarse ground coffee—and consequently prevents the loss of the highly volatile constituents of the ten percent of coarse-ground particles, and at the same time gives a full-body extraction.

Making and Filling Containers

As stated before, a large proportion of the coffee sold in the United States is put up into packages, ready for brewing. Such containers are grouped under the name of the material of which they are made; such as tin, fiber, cardboard, paper, wood, and combinations of these materials, such as a fiber can with tin top and bottom. Generally, coffee containers are lined with chemically treated paper or foil to keep in the aroma and flavor, and to keep out moisture and contaminating odors.

As the package business grew in the United States, the machinery manufacturers kept pace; until now there are machines that, in one continuous operation, open up a "flat" paper carton, seal the bottom fold, line the carton with a protecting paper, weigh the coffee as it comes down from an overhead hopper into the carton, fold the top and seal it, and then wrap the whole package in a waxed or paraffined paper, delivering the package ready for shipment without having been touched by a human hand from the first operation to the last. Such a machine can put out fifteen to eighteen thousand packages a day.

Another type of machine automatically manufactures two and three-ply paper cans such as are used widely for cereal packages. It winds the ribbons of heavy paper in a spiral shape, automatically gluing the papers together to make a can that will not permit its contents to leak out. The machine turns out its product in long cylinders, like mailing tubes, which are cut into the desired lengths to make the cans. The paper or tin tops and bottoms are stamped out on a punch press.

Coffee cans are generally filled by hand; that is, the can is placed under the spout of an automatic filling and weighing machine by an operator who slips on the cover when the can is properly filled. The weighing machine has a hopper which lets the coffee down into a device that gauges the correct amount, say a pound or two pounds, and then pours it into the can. The machine weighs the can and its contents, and if they do not show the exact predetermined weight, the device automatically operates to supply the necessary quantity. After weighing, the can is carried on a traveling belt to the labeling machine, where the label is automatically applied and glued. Then the can is put through a drying compartment to make the label stick quickly.

The girl is feeding the "flats" into an Improved Johnson bottom-sealer. The carton travels to a Scott weigher on the right and thence to the top-sealer on the left

Paper bags are filled much the same way as the tin and the fiber cans. In fact, some packers fill their paper and fiber cartons by the same system; although the tendency among the largest companies is to instal the complete automatic packaging equipment, because of its speed and economy in packaging. Frequently, the weighing machines are used in filling wooden and fiber drums holding twenty-five, fifty, and one hundred pounds of coffee, to be sold in bulk to the retailer.

Three Types of Automatic Coffee-Weighing Machines

Left—Duplex net weigher. Center—Pneumatic cross-weight machine. Right—Scott net weigher

Coffee Additions and Fillers

In all large coffee-consuming countries, coffee additions and fillers have always been used. Large numbers of French, Italian, Dutch, and German consumers insist on having chicory with their coffee, just as do many Southerners in the United States.

The chief commercial reason for using coffee additions and fillers is to keep down the cost of blends. For this purpose, chicory and many kinds of cooked cereals are most generally used; while frequently roasted and ground peas, beans, and other vegetables that will not impair the flavor or aroma of the brew, are employed in foreign countries. Before Parliament passed the Adulterant Act, some British coffee men used as fillers cacao husks, acorns, figs, and lupins, in addition to chicory and the other favorite fillers.

Up to the year 1907, when the United States Food and Drugs Act became effective, chicory and cereal additions were widely used by coffee packers and retailers in this country. With the enforcement of the law requiring the label of a package to state when a filler is employed, the use of additions gradually fell off in most sections.

In botanical description and chemical composition chicory, the most favored addition, has no relationship with coffee. When roasted and ground, it resembles coffee in appearance; but it has an entirely different flavor. However, many coffee-drinkers prefer their beverage when this alien flavor has been added to it.

Treated Coffees and Dry Extracts

The manufacture of prepared, or refined, coffees has become an important branch of the business in the United States and Europe. Prepared coffees can be divided into two general groups: treated coffees, from which the caffein has been removed to some degree; and dry coffee extracts (soluble coffee), which are readily dissolved in a cup of hot or cold water.

To decaffeinate coffee, the most common practise is to make the green beans soft by steaming under pressure, and then to apply benzol or chloroform or alcohol to the softened coffee to dissolve and to extract the caffein. Afterward, the extracting solvents are driven out of the coffee by re-steaming. However, chemists have not yet been able to expel all the caffein in treating coffee commercially, the best efforts resulting in from 0.3 to 0.07 percent remaining. After treatment, the coffee beans are then roasted, packed, and sold like ordinary coffee.

Vacuum drum drier, No. 1 size; diameter of drum, 12 inches; length, 20 inches; used for converting coffee extract and other liquids into dry powder form. This is the smallest size, and was developed for drying smaller quantities of liquids than could be handled economically in the larger sizes. To provide accessibility of the interior for cleansing, the outer casing may be moved back on the track of the bedplate (as shown in the cut), so that free access may be had to the drum and interior of the casing.

Used to concentrate coffee extracts and other liquids. The tubes are easily reached through the open door for cleansing. Interior of the vapor body is reached through a manhole.

Rear View of Drum Drier Vacuum drum dryer. No. 1 size; rear view, showing outer casing rolled back from the drum.

This shows the interior arrangement and principle of operation. The drawing represents a larger size than the photograph, and while the arrangement of some parts is slightly different, the principle of operation is the same.

UNITS USED IN THE MANUFACTURE OF SOLUBLE COFFEEIn manufacturing dry coffee extract in the form of a powder that is readily soluble in water, the general method is to extract the drinking properties from ground roasted coffee by means of water, and to evaporate the resulting liquid until only the coffee powder is left. Several methods have been developed and patented to prevent

Comments (0)