All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

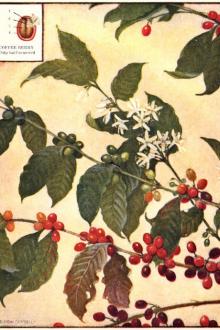

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

Apparently the variation in caffein content is largely due to the genus of the tree from which the berry comes, but it is also quite probable that the nature of the soil and climatic conditions play an important part. In the light of what has been accomplished in the field of agricultural research, it does not seem improbable that a man of Burbank's ability and foresight could successfully develop a series of coffees possessed of all the cup qualities inherent in those now used, but totally devoid of caffein. Whether this is desirable or not is a question to be considered in an entirely different light from the possibility of its accomplishment.

The variation in the caffein content of coffee at different intensities of roasting, as shown in Table III[140] is, of course, primarily dependent upon the original content of the green. A considerable portion of the caffein is sublimed off during roasting, thus decreasing the amount in the bean. The higher the roast is carried, the greater the shrinkage; but, as the analyses in the above table show, the loss of caffein proceeds out of proportion to the shrinkage, for the percentage of caffein constantly decreases with the increase in color. If the roast be carried almost to the point of carbonization, as in the case of the "Italian roast," the caffein content will be almost nil. This is not a suitable coffee for one desiring an almost caffein-free drink, for the empyreumatic products produced by this excessive roasting will be more toxic by far than the caffein itself would have been.

Caffein-free Coffee

The demand for a caffein-free coffee may be attributed to two causes, namely: the objectionable effect which caffein has upon neurasthenics; and the questionable advertising of the "coffee-substitute" dealers, who have by this means persuaded many normal persons into believing that they are decidedly sub-normal. As a result of this demand, a variety of decaffeinated coffees have been placed on the market. Just why the coffee men have not taken advantage of naturally caffein-free coffees, or of the possibility of obtaining coffees low in caffein content by chemical selection from the lines now used, is a difficult question to answer.

In the endeavor to develop a commercial decaffeinated coffee the first method of procedure was to extract the caffein from roasted coffee. This method had its advantages and its disadvantages, of which the latter predominated. The caffein in the roasted coffee is not as tightly bound chemically as in the green coffee, and is, therefore, more easily extracted. Also, the structure of the roasted bean renders it more readily penetrable by solvents than does that of the green bean. However, the great objection to this method arises from the fact that at the same time as the caffein is extracted, the volatile aromatic and flavoring constituents of the coffee are removed also. These substances, which are essential for the maintenance of quality by the coffee, though readily separated from the caffein, can not be returned to the roasted bean with any degree of certainty. This virtually insurmountable obstacle forced the abandonment of this mode of attack.

In order to avoid this action, the attention of investigators was directed to extraction of the alkaloid in question from the green bean. Because of the difficulty of causing the solvent to penetrate the bean, recourse to grinding resulted. This greatly facilitated the desired extraction, but a difficulty was encountered when the subsequent roasting was attempted. The irregular and broken character of the ground green beans resisted all attempts to produce practically a uniformly roasted, highly aromatic product from the ground material.

Avoidance of this lack of uniformity in the product, and the great desirability to duplicate the normal bean as far as possible, necessitated the development of a method of extraction of the caffein from the whole raw bean without a permanent alteration of the shape thereof. The close structure of the green bean, and its consequent resistance to penetration by solvents, and the existence of the caffein in the bean as an acid salt, which is not easily soluble, offered resistance to successful extraction.

As a means of overcoming the difficulty of structure, the beans were allowed to stand in water in order to swell, or the cells were expanded by treatment with steam, or the beans were subjected to the action of some "cellulose-softening acids," such as acetic acid or sulphur dioxid. As a method of facilitating the mechanical side of extraction without deleterious effects, the treatment of the coffee with steam under pressure, as utilized in the patented process of Myer, Roselius, and Wimmer,[141] is probably the safest.

Many ingenious methods have been devised for the ready removal of the caffein from this point on. Several processes employ an alkali, such as ammonium hydroxid, to free the caffein from the acid; or an acid, such as acetic, hydrochloric, or sulphurous, is used to form a more soluble salt of caffein. Other procedures effect the dissociation of the caffein-acid salt by dampening or immersion in a liquid and subjecting the mass to the action of an electric current.

The caffein is usually extracted from the beans by benzol or chloroform, but a variety of solvents may be employed, such as petrolic ether, water, alcohol, carbon tetrachloride, ethylene chloride, acetone, ethyl ether, or mixtures or emulsions of these. After extraction, the beans may be steam distilled to remove and to recover any residual traces of solvent, and then dried and roasted. It is said[142] that by heating the beans before bringing them into contact with steam, not only is an economy of steam effected, but the quality of the resultant product is improved.

One clever but expensive method[143] of preparing caffein-free coffee consists in heating the beans under pressure, with some substance, such as sodium salicylate, with the resultant formation of a more soluble and more easily steam-distillable compound of caffein. The beans are then steam distilled to remove the caffein, dried, and roasted.

Another process of peculiar interest is that of Hubner,[144] in which the coffee beans are well washed and then spread in layers and kept covered with water at 15° C. until limited germination has taken place, whereupon the beans are removed and the caffein extracted with water at 50° C. It is claimed by the inventor that sprouting serves to remove some of the caffein, but it is quite probable that the process does nothing more than accomplish simple aqueous extraction.

In the majority of these processes the flavor of the resultant product should be very similar to natural roasted coffee. However, in the cases where aqueous extraction is employed, other substances besides caffein are removed that are replaced in the bean only with difficulty. The resultant product accordingly is very likely to have a flavor not entirely natural. On the other hand, beans from which the caffein is extracted with volatile solvents, if the operation be conducted carefully, should give a natural-tasting roast. Any residual traces of the solvent left in the bean are volatilized upon roasting.

Some of the caffein-free coffees on the market show upon analysis almost as much caffein as the natural bean. Those manufactured by reliable concerns, however, are virtually caffein-free, their content of the alkaloid varying from 0.3 to 0.07 percent as opposed to 1.5 percent in the untreated coffee. Thus, although actually only caffein-poor, in order to get the reaction of one cup of ordinary coffee one would have to drink an unusual amount of the brew made from these coffees.

The Aromatic Principles of Coffee

To ascertain just what substance or substances give the pleasing and characteristic aroma to coffee has long been the great desire of both practical and scientific men interested in the coffee business. This elusive material has been variously called caffeol, caffeone, "the essential oil of coffee," etc., the terms having acquired an ambiguous and incorrect significance. It is now generally agreed that the aromatic constituent of coffee is not an essential oil, but a complex of compounds which usage has caused to be collectively called "caffeol."

These substances are not present in the green bean, but are produced during the process of roasting. Attempts at identification and location of origin have been numerous; and although not conclusive, still have not proven entirely futile. One of the first observations along this line was that of Benjamin Thompson in 1812. "This fragrance of coffee is certainly owing to the escape of a volatile aromatic substance which did not originally exist as such in the grain, but which is formed in the process of roasting it." Later, Graham, Stenhouse, and Campbell started on the way to the identification of this aroma by noting that "in common with all the valuable constituents of coffee, caffeone is found to come from the soluble portion of the roasted seed."[145]

Comparison of the aroma given off by coffee during the roasting process with that of fresh-ground roasted coffee shows that the two aromas, although somewhat different, may be attributed to the same substances present in different proportions in the two cases. Recovery and identification of the aromatic principles escaping from the roaster would go far toward answering the question regarding the nature of the aroma. Bernheimer[146] reported water, caffein, caffeol, acetic acid, quinol, methylamin, acetone, fatty acids and pyrrol in the distillate coming from roasting coffee. The caffeol obtained by Bernheimer in this work was believed by him to be a methyl derivative of saligenin. Jaeckle[147] examined a similar product and found considerable quantities of caffein, furfurol, and acetic acid, together with small amounts of acetone, ammonia, trimethylamin, and formic acid. The caffeol of Bernheimer could not be detected. Another substance was separated also, but in too small a quantity to permit complete identification. This substance consisted of colorless crystals, which readily sublimed, melted at 115° to 117° C., and contained sulphur. The crystals were insoluble in water, almost insoluble in alcohol, but readily soluble in ether.

By distilling roasted coffee with superheated steam, Erdmann[148] obtained an oil consisting of an indifferent portion of 58 percent and an acid portion of 42 percent, consisting mainly of a valeric acid, probably alphamethylbutyric acid. The indifferent portion was found to contain about 50 percent furfuryl alcohol, together with a number of phenols. The fraction containing the characteristic odorous constituent of coffee boiled at 93° C. under 13 mm. pressure. The yield of this latter principle was extremely small, only about 0.89 gram being procured from 65 kilos of coffee.

Pyridin was also shown to be present in coffee by Betrand and Weisweiller[149] and by Sayre.[150] As high as 200 to 500 milligrams of this toxic compound have been obtained from 1 kilogram of freshly roasted coffee.

As stated above, the empyreumatic volatile aromatic constituents of the coffee are without question formed during and by the roasting process. According to Thorpe,[151] the most favorable temperature for development of coffee odor and flavor is about 200° C. Erdmann claimed to have produced caffeol by gently heating together caffetannic acid, caffein, and cane sugar. Other investigators have been unable to duplicate this work. Another authority,[152] giving it the empirical formula C8H10O2, states that

Comments (0)