All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

CHAPTER II

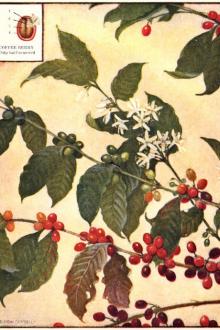

HISTORY OF COFFEE PROPAGATION

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World, and of its introduction into the New--A romantic coffee adventure Page 5

CHAPTER III

EARLY HISTORY OF COFFEE DRINKING

Coffee in the Near East in the early centuries--Stories of its origin--Discovery by physicians and adoption by the Church--Its spread through Arabia, Persia, and Turkey--Persecutions and Intolerances--Early coffee manners and customs Page 11

CHAPTER IV

INTRODUCTION OF COFFEE INTO WESTERN EUROPE

When the three great temperance beverages, cocoa, tea, and coffee, came to Europe--Coffee first mentioned by Rauwolf in 1582--Early days of coffee in Italy--How Pope Clement VIII baptized it and made it a truly Christian beverage--The first Europe

Read free book «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Read book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author - William H. Ukers

The Act also is intended to prevent the sale of coffees under trade names that do not properly belong to them. For example, only coffees grown on the island of Java can properly be labeled and sold as Javas; coffees from Sumatra, Timor, etc., must be sold under their respective names. Food Inspection Decision No. 82, which limited the use of the term Java to coffee grown on the island of Java, was sustained in a service and regulatory announcement issued in January, 1916. Likewise the name Mocha may be used only for coffees of Arabia. Before the pure-food law was enacted, it was frequently the custom to mix Bourbon Santos with Mocha and to sell the blend as Mocha. Also, Abyssinian coffees were generally known in the trade as Longberry Mocha, or just straight Mocha; and Sumatra growths were practically always sold as Javas. Traders used the names of Mocha and Java because of the high value placed upon these coffees by consumers, who, before Brazil dominated the market, had practically no other names for coffee.

One of the most celebrated coffee cases under the Pure Food Act was tried in Chicago, February, 1912. The question was, whether in view of the long-standing trade custom, it was still proper to call an Abyssinian coffee (Longberry Mocha) Mocha. The defendant was charged with misbranding, because he sold as Java and Mocha a coffee containing Abyssinian coffee. The court decided that the product should be called Abyssinian Mocha;[321] but since then, general acceptance has obtained of the government's viewpoint as expressed in F.I.D. No. 91, which was that only coffee grown in the province of Yemen in Arabia could properly be known as Mocha coffee.

Another important ruling, concerning coffee buyers and sellers, prohibits the importation of green coffees coated with lead chromate, Prussian blue, and other substances, to give the beans a more stylish appearance than they have normally. Such "polished" coffees find great favor in the European markets, but are now denied admittance here.

The Board of Food and Drug Inspection decided in 1910 against a trade custom that had prevailed until then of calling Minãs coffee Santos when shipped through Santos, instead of Rio.[322]

For years a practise obtained of rebagging certain Central American growths in New York. In this way Bucaramangas frequently were transformed into Bogotas, Rios became Santos, Bahias and Victorias were sold as Rios, and the misbranding of peaberry was quite common. A celebrated case grew out of an attempt by a New York coffee importer and broker to continue one of these practises after the Pure Food Act made it a criminal offense. The defendants, who were found guilty of conspiracy, and who were fined three thousand dollars each, mixed, re-packed and sold under the name P.A.L. Bogota, a well known Colombian mark, eighty-four bags of washed Caracas coffee.[323]

After an exchange of views with the United States Board of Food and Drug Inspection, the New York Coffee Exchange decided that, after June 1, 1912, it would abolish all grades of coffee under the Exchange type No. 8.

The practise in Holland of grading Santos coffees—by selecting beans most like Java beans, and polishing and coloring them to add verisimilitude—known as "manipulated Java," became such a nuisance in 1912 that United States consuls refused to certify invoices to the United States unless accompanied by a declaration that the produce was "pure Java, neither mixed with other kinds nor counterfeited."

The United States Bureau of Chemistry ruled in February, 1921, that Coffea robusta could not be sold as Java coffee, or under any form of labeling which tended either directly or indirectly to create the impression that it was Coffea arabica, so long and favorably known as Java coffee. This was in line with the Department of Agriculture's previous definition that coffee was the seed of the Coffea arabica or Coffea liberica, and that Java coffee was Coffea arabica from Java. Coffea robusta was barred from deliveries on the New York Coffee Exchange in 1912.

During the greater part of the year 1918, the United States government assumed virtually full control of coffee trading. It was a war-time measure, and was intended to prevent speculation in coffee contracts and freight rates, to cut down the number of vessels carrying coffee to this country so as to provide more ships for transporting food and soldiers to Europe, and to put the coffee merchants on rations during the stress of war. On February 4, 1918, importers and dealers were placed under license; and two days later, rules were issued through the Food Administration fixing the maximum price for coffee for the spot month in the "futures" markets at eight and a half cents, prohibiting dealers from taking more than normal pre-war profits, or holding supplies in excess of ninety days' requirements, and greatly limiting resales. On May 8, the United States Shipping Board fixed the "official" freight rate from Rio de Janeiro to New York at one dollar and fifty cents per bag, which, without control, had risen to as high as four dollars and more, as compared with the ordinary rate of thirty-five cents before the war. On January 12, 1919, two months after the armistice was signed, the rules were withdrawn, and the coffee trade was left to carry on its business under its own direction.

Some Well Known Green Coffee Marks

Practically every bag of good quality green coffee is imprinted with a brand which indicates by whom it was shipped. These imprints are known in the trade as "green coffee marks." Many of them, through long usage, have become celebrated in international trade. One of the most famous was HLOG. This stood for "Heaven's Light Our Guide," and was owned by John O'Donohue's Sons. For many years it was used on Mocha coffee, but it is now out of existence. Other well-known Mocha marks are M R (Maurice Ries) with the figure of a camel, a star, or deer's head between the letters; L F or L B (Livierato Frères); C F or C B (Caracanda Frères).

Bogota marks includes PAL (in triangle) Bogota (P.A. Lopez & Co.); Camelia; Pinzon & Co.; Salazar; AOL (in triangle) Bogota; and Carmencita Manizales Excelso (Steinwender, Stoffregen & Co.).

Among the best known Medellin marks are FAC & H (F.A. Correa & Sons): PEC & C (Pedro Estrado Co.); LMT & C (Louis M. Torro & Co.); A & C (A. Angel & Co.); E C S Medellin Excelso (Eppens, Smith Co.); Balzacbro Medellin Excelso (Balzac Bros.); La Rambla (Banco Lopez); and Don Carlos Medellin Excelso (Steinwender, Stoffregen & Co.).

Caracas marks show J P P & H (Juan Pablo Perez & Sons); HLB & C (H.L. Boulton & Co.); FST & C (Filipe S. Toledo & Co.); JLG (J.L. Garrondona); and many others. Kolster (Kolster & Co.) is a well known Puerto Cabello mark.

Maracaibos bear numerous marks, chief among which are: M & C (Menda & Co.); Cogollo (Cogollo & Co.); Fossi (Fossi & Co.); B M & C (Breur. Moller & Co.); B & C (Blohm & Co.); FST & C (Filipe S. Toledo & Co.); V D R & C (Van Dessel, Rodo & Co.); and J E C & C over R G E (J.E. Carret & Co.).

A prominent Mexican mark is P A N (Rafael del Castillo & Co.).

Brazil coffee is usually marked merely with the initials of the firm or bank financing the shipment. Some representative Brazilian marks are: Aronco (in rectangle) Brazil; J A & Co (in rectangle) Brazil Rosebud; J A & Co (in rectangle) Brazil Bourbona—all used by J. Aron & Company; S S C (in circle) Rio; S S C (in triangle) Santos; both used by Steinwender, Stoffregen & Co.; Sions M/M Bourbns (Sion & Co.); and Nossack V S S C (in swastika), used by Nossack & Co.

There are hundreds of other marks. In most countries they change so often that one rarely stands out above the rest.

The trade values, bean characteristics, and cup merits of the leading coffees of commerce, with a "Complete Reference Table of the Principal Kinds of Coffee Grown in the World"—Appearance, aroma, and flavor in cup-testing—How experts test coffee—A typical sample-roasting and cup-testing outfit

More than a hundred different kinds of coffee are bought and sold in the United States. All of them belong to the same botanical genus, and practically all to the same species, the Coffea arabica; but each has distinguishing characteristics which determine its commercial value in the eyes of the importers, roasters, and distributers.

The American trade deals almost exclusively in Coffea arabica, although in the latter years of the World War increasing quantities of robusta and liberica growths were imported, largely because of the scarcity of Brazilian stocks and the improvement in the preparation methods, especially in the case of robustas. Considerable quantities of robusta grades were sold in the United States before 1912, but trading in them fell off when the New York Coffee and Sugar Exchange prohibited their delivery on Exchange contracts after March 1, 1912.

All coffees used in the United States are divided into two general groups, Brazils and Milds. Brazils comprise those coffees grown in São Paulo, Minãs Geraes, Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, Victoria, and other Brazilian states. The Milds include all coffees grown elsewhere. In 1921 Brazils made up about three-fourths of the world's total consumption. They are regarded by American traders as the "price" coffees, while Milds are considered as the "quality" grades.

Brazil coffees are classified into four great groups, which bear the names of the ports through which they are exported; Santos, Rio, Victoria, and Bahia. Santos coffee is grown principally in the state of São Paulo; Rio, in the state of Rio de Janeiro and the state of Minãs Geraes; Victoria, in the state of Espirito Santo; and Bahia in the state of Bahia. All of these groups are further subdivided according to their bean characteristics and the districts in which they are produced.

Brazil Coffee Characteristics

Santos. Santos coffees, considered as a whole, have the distinction of being the best grown in Brazil. Rios rank next, Victorias coming third in favor, and Bahias fourth. Of the Santos growths the best is that known in the trade as Bourbon, produced by trees grown from Mocha seed (Coffea arabica) brought originally from the French island colony of Bourbon (now Réunion) in the Indian Ocean. The true Bourbon is obtained from the first few crops of Mocha seed. After the third or fourth year of bearing, the fruit gradually changes in form, yielding in the sixth year the flat-shaped beans which are sold under the trade name of Flat Bean Santos. By that time, the coffee has lost most of its Bourbon characteristics. The true Bourbon of the first and second crops is a small bean, and resembles the Mocha, but makes a much handsomer roast with fewer "quakers". The Bourbons grown in the Campinas district often have a red center.

Showing the Principal Coffee-Producing States and Shipping Ports

Copyright 1922 by The Tea and

Comments (0)