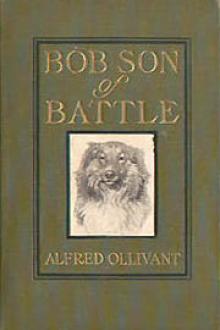

Bob, Son of Battle by Alfred Ollivant (crime books to read TXT) 📕

The latter, small, old, with shrewd nut-brown countenance, was Tammas Thornton,, who had served the Moores of Kenmuir for more than half a century. The other, on top of the stack, wrapped apparently in gloomy meditation, was Sam'l Todd. A solid Dales-- man, he, with huge hands and hairy arms; about his face an uncomely aureole of stiff, red hair; and on his features, deep-seated, an expression of resolute melancholy.

"Ay, the Gray Dogs, bless 'em!" the old man was saying. "Yo' canna beat 'em not nohow. Known 'em ony time this sixty year, I have, and niver knew a bad un yet. Not as I say, mind ye, as any on 'em cooms up to Rex son o' Rally. Ah, he was a one, was Rex! We's never won Cup since his day."

"Nor niver shall agin, yo' may depend," said the other gloomily.

Tammas clucked irritably.

"G'long, Sam'! Tod

Read free book «Bob, Son of Battle by Alfred Ollivant (crime books to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Alfred Ollivant

- Performer: -

Read book online «Bob, Son of Battle by Alfred Ollivant (crime books to read TXT) 📕». Author - Alfred Ollivant

“His heart is good, your Leddyship, if his manners are not,” M’Adam answered, smiling.

“Liar!” came a loud voice in the silence. Lady Eleanour looked up, hot with indignation, and half rose from her seat. But M’Adam merely smiled.

“Wullie, turn and mak’ yer bow to the leddy,” he said. “They’ll no hurt us noo we’re up; it’s when we’re doon they’ll flock like corbies to the carrion.”

At that Red Wull walked up to Lady Eleanour, faintly wagging his tail; and she put her hand on his huge bull head and said, “Dear old Ugly!” at which the crowd cheered in earnest.

After that, for some moments, the only sound was the gentle ripple of the good lady’s voice and the little man’s caustic replies.

“Why, last winter the country was full of Red Wull’s doings and yours. It was always M’Adam and his Red Wull have done this and that and the other. I declare I got quite tired of you both, I heard such a lot about you.”

The little man, cap in hand, smiled, blushed and looked genuinely pleased.

“And when it wasn’t you it was Mr. Moore and Owd Bob.”

“Owd Bob, bless him!” called a stentorian voice. “There cheers for oor Bob!”

‘Ip! ‘ip! ‘ooray!” It was taken up gallantly, and cast from mouth to mouth; and strangers, though they did not understand, caught the contagion and cheered too; and the uproar continued for some minutes.

When it was ended Lady Eleanour was standing up, a faint flush on her cheeks and her eyes flashing dangerously, like a queen at bay.

“Yes,” she cried, and her clear voice thrilled through the air like a trumpet. “Yes; and now three cheers for Mr. M’Adam and his Red Wull! Hip! hip—”

“Hooray!” A little knowt of stalwarts at the back—James Moore, Parson Leggy, Jim Mason, and you may be sure in heart, at least, Owd Bob—responded to the call right lustily. The crowd joined in; and, once off, cheered and cheered again.

“Three cheers more for Mr. M’Adam!”

But the little man waved to them.

“Dinna be bigger heepocrites than ye can help,” he said. “Ye’ve done enough for one day, and thank ye for it.”

Then Lady Eleanour handed him the Cup.

“Mr. M’Adam, I present you with the Champion Challenge Dale Cup, open to all corners. Keep it, guard it, love it as your own, and win it again if you can. Twice more and it’s yours, you know, and it will stop forever beneath the shadow of the Pike. And the right place for it, say I—the Dale Cup for Dalesmen.”

The little man took the Cup tenderly.

“It shall no leave the Estate or ma hoose, yer Leddyship, gin Wullie and I can help it,” he said emphatically.

Lady Eleanour retreated into the tent, and the crowd swarmed over the ropes and round the little man, who held the Cup beneath his arm.

Long Kirby laid irreverent hands upon it.

“Dinna finger it!” ordered M’Adam.

“Shall!”

“Shan’t! Wullie, keep him aff.” Which the great dog proceeded to do amid the laughter of the onlookers.

Among the last, James Moore was borne past the little man. At sight of him, M’Adam’s face assumed an expression of intense concern.

“Man, Moore!” he cried, peering forward as though in alarm; “man, Moore, ye’re green—positeevely verdant. Are ye in pain?” Then, catching sight of Owd Bob, he started back in affected horror.

“And, ma certes! so’s yer dog! Yer dog as was gray is green. Oh, guid life! “—and he made as though about to fall fainting to the ground.

Then, in bantering tones: “Ah, but ye shouldna covet—

“He’ll ha’ no need to covet it long, I can tell yo’,” interposed Tammas’s shrill accents.

“And why for no?”

“Becos next year he’ll win it fra yo’. Oor Bob’ll win it, little mon. Why? thot’s why.”

The retort was greeted with a yell of applause from the sprinkling of Dalesmen in the crowd.

But M’Adam swaggered away into the tent, his head up, the Cup beneath his arm, and Red Wull guarding his rear.

“First of a’ ye’ll ha’ to beat Adam M’Adam and his Red Wull!” he cried back proudly.

Chapter XI. OOR BOB

M’ADAM’S pride in the great Cup that now graced his kitchen was supreme. It stood alone in the very centre of the mantelpiece, just below the old bell-mouthed blunderbuss that hung upon the wall. The only ornament in the bare room, it shone out in its silvery chastity like the moon in a gloomy sky.

Por once the little man was content. Since his mother’s death David had never known such peace. It was not that his father became actively kind; rather that he forgot to be actively unkind.

“Not as I care a brazen button one way or t’ither,” the boy informed Maggie.

“Then yo’ should,” that proper little person replied.

M’Adam was, indeed, a changed being. He forgot to curse James Moore; he forgot to sneer at Owd Bob; he rarely visited the Sylvester Arms, to the detriment of Jem Burton’s pocket and temper; and he was never drunk.

“Soaks ‘isseif at home, instead,” suggested Tammas, the prejudiced. But the accusation was untrue.

“Too drunk to git so far,” said Long Kirby, kindly man.

“I reck’n the Cup is kind o’ company to him,” said Jim Mason. “Happen it’s lonesomeness as drives him here so much.” And happen you were right, charitable Jim.

“Best mak’ maist on it while he has it, ‘cos he’ll not have it for long,” Tammas remarked amid applause.

Even Parson Leggy allowed—rather reluctantly, indeed, for he was but human—that the little man was changed wonderfully for the better.

“But I am afraid it may not last,” he said. “We shall see what happens when Owd Bob beats him for the Cup, as he certainly will. That’ll be the critical moment.”

As things were, the little man spent all his spare moments with the Cup between his knees, burnishing it and crooning to Wullie:

“I never saw a fairer, I never lo’ed a dearer, And neist my heart I’ll wear her, For fear my jewel tine.”

There, Wullie! look at her! is she no bonthe? She shines like a twinkle—twinkle in the sky.” And he would hold it out at arm’s length, his head cocked sideways the better to scan its bright beauties.

The little man was very jealous for his treasure. David might not touch it; might not smoke in the kitchen lest the fumes should tarnish its glory; while if he approached too closely he was ordered abruptly away.

“As if I wanted to touch his nasty Cup!” he complained to Maggie. “I’d sooner ony day—”

“Hands aff, Mr. David, immediate! ‘ she cried indignantly. “‘Pertinence, indeed!” as she tossed her head clear of the big fingers that were fondling her pretty hair.

So it was that M’Adam, on coming quietly-into the kitchen one day, was consumed with angry resentment to find David actually handling the object of his reverence; and the manner of his doing it added a thousandfold to the offence.

The boy was lolling indolently against the mantelpiece, his fair head shoved right into the Cup, his breath dimming its lustre, and his two hands, big and dirty, slowly revolving it before his eyes.

Bursting with indignation, the little man crept up behind the boy. David was reading through the long list of winners.

“Theer’s the first on ‘em,” he muttered, shooting out his tongue to indicate the locality: “‘Andrew Moore’s Rough, 178—.’ And theer agin —’ James Moore’s Pinch, 179—.’ And agin—‘Beck, 182—.’ Ah, and theer’s ‘im Tammas tells on! ‘Rex, 183—,’ and Rex, 183—.’ Ay, but he was a rare un by all tell-in’s! If he’d nob’but won but onst agin!

Ah, and theer’s none like the Gray Dogs—they all says that, and I say so masel’; none like the Gray Dogs o’ Kenmuir, bless ‘em! And we’ll win agin too—” he broke off short; his eye had travelled down to the last name on the list.

“‘M’Adam’s Wull’!” he read with unspeakable contempt, and put his great thumb across the name as though to wipe it out. “‘M’-Adam’s Wull’! Goo’ gracious sakes! P-hg-h-r-r! “—and he made a motion as though to spit upon the ground.

But a little shoulder was into his side, two small fists were beating at his chest, and a shrill voice was yelling: “Devil! devil! stan’ awa’ ! “—and he was tumbled precipitately away from the mantelpiece, and brought up abruptly against the side-wall.

The precious Cup swayed on its ebony stand, the boy’s hands, rudely withdrawn, almost overthrowing it. But the little man’s first impulse, cursing and screaming though he was, was to steady it.

“‘M’Adam’s Wull’! I wish he was here to teach ye, ye snod-faced, ox-limbed profleegit!” he cried, standing in front of the Cup, his eyes blazing.

“Ay, ‘WAdam’s Wull’! And why not ‘M’Adam’s Wull’? Ha’ ye ony objection to the name?”

“I didn’t know yo’ was theer,” said David, a thought sheepishly.

“Na; or ye’d not ha’ said it.”

“I’d ha’ thought it, though,” muttered the boy.

Luckily, however, his father did not hear. He stretched his hands up tenderly for the Cup, lifted it down, and began reverently to polish the dimmed sides with his handkerchief.

“Ye’re thinkin’, nae doot,” he cried, casting up a vicious glance at David, “that Wullie’s no gude enough to ha’ his name alangside o’ they cursed Gray Dogs. Are ye no? Let’s ha’ the truth for aince—for a diversion.”

” Reck’n he’s good enough if there’s none better,” David replied dispassionately.

“And wha should there be better? Tell me that, ye mucide gowk.”

David smiled.

“Eh, but that’d be long tellin’, he said.

“And what wad ye mean by that?” his father cried.

“Nay; I was but thinkin’ that Mr. Moore’s Bob’ll look gradely writ under yon.” He pointed to the vacant space below Red Wull’s name.

The little man put the Cup back on its pedestal with hurried hands. The handkerchief dropped unconsidered to the floor; he turned and sprang furiously at the boy, who stood against the wall, still smiling; and, seizing him by the collar of his coat, shook him to and fro with fiery energy.

“So ye’re hopin’, prayin’, nae doot, that James Moore—curse him !—will win ma Cup awa’ from me, yer am dad. I wonder ye’re no ‘shamed to crass ma door! Ye live on me; ye suck ma blood, ye foul-mouthed leech. Wullie and me brak’ oorsel’s to keep ye in .iioose and hame—and what’s yer gratitude? ‘Ye plot to rob us of oor rights.”

He dropped the boy’s coat and stood back. No rights about it,” said David, still keeping his temper.

“If I win is it no ma right as muckle as ony Englishman’s?”

Red Wull, who had heard the rising voices, came trotting in, scowled at David, and took his stand beside his master.

“Ah, if yo’ win it,” said David, with signfficant emphasis on the conjunction.

“And wha’s to beat us?”

David looked at his father in well-affected surprise.

“I tell yo’ Owd Bob’s mm’,” he answered.

“And what if he is?” the other cried.

“Why, even yo’ should know so much,” the boy sneered.

The little man could not fail to understand.

“So that’s it!” he said. Then, in a scream, with one finger pointing to the great dog:

“And what o’ him? What’ll ma Wullie be doin’ the while? Tell me that, and ha’ a care! Mind ye, he stan’s here hearkenin’!” And, indeed, the Tailless Tyke was bristling for battle.

David did not like the look of things; and edged away toward the door.

“What’ll Wullie be doin’, ye chicken-hearted brock?” his father cried.

‘Im?” said the boy, now close on the door! ‘Im?” he said, with a slow contempt that made the red bristles quiver on the dog’s neck. “Lookin’ on, I

Comments (0)