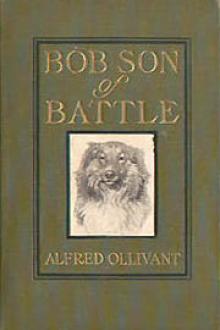

Bob, Son of Battle by Alfred Ollivant (crime books to read TXT) 📕

The latter, small, old, with shrewd nut-brown countenance, was Tammas Thornton,, who had served the Moores of Kenmuir for more than half a century. The other, on top of the stack, wrapped apparently in gloomy meditation, was Sam'l Todd. A solid Dales-- man, he, with huge hands and hairy arms; about his face an uncomely aureole of stiff, red hair; and on his features, deep-seated, an expression of resolute melancholy.

"Ay, the Gray Dogs, bless 'em!" the old man was saying. "Yo' canna beat 'em not nohow. Known 'em ony time this sixty year, I have, and niver knew a bad un yet. Not as I say, mind ye, as any on 'em cooms up to Rex son o' Rally. Ah, he was a one, was Rex! We's never won Cup since his day."

"Nor niver shall agin, yo' may depend," said the other gloomily.

Tammas clucked irritably.

"G'long, Sam'! Tod

Read free book «Bob, Son of Battle by Alfred Ollivant (crime books to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Alfred Ollivant

- Performer: -

Read book online «Bob, Son of Battle by Alfred Ollivant (crime books to read TXT) 📕». Author - Alfred Ollivant

The Master stood over his fallen enemy and looked sternly down at him.

“I’ve put up wi’ more from you, M’Adam, than I would from ony other man, ” he said. “But this is too much—comin’ here at night -wi’ loaded arms, scarin’ the wimmen and childer oot o’ their lives, and I can but think meanin’ worse. If yo’ were half a man I’d gie yo’ the finest thrashin’ iver yo’ had in yer life. But, as yo’ know well, I could no more hit yo’ than I could a woman. Why yo’ve got this down on me yo’ ken best. I niver did yo’ or ony ither mon a harm. As to the Cup, I’ve got it and I’m goin’ to do ma best to keep it—it’s for yo’ to win it from me if yo’ can o’ Thursday. As for what yo’ say o’ David, yo’ know it’s a lie. And as for what yo’re drivin’ at wi’ yer hints and mysteries, I’ve no more idee than a babe unborn. Noo I’m goin’ to lock yo’ up, yo’re not safe abroad. I’m thinkin’ I’ll ha’ to hand ye o’er to the p’lice.”

With the help of Sam’l he half dragged, half supported the stunned little man across the yard; and shoved him into a tiny semisubterraneous room, used for the storage of coal, at the end of the farm-buildings.

“Yo’ think it over that side, ma lad,” called the Master grimly, as he turned the key, “and I will this.” And with that he retired to bed.

Early in the morning he went to release his prisoner. But he was a minute too late. For scuttling down the slope and away was a little black-begrimed, tottering figure with white hair blowing in the wind. The little man had broken away a wooden hatchment which covered a manhole in the wall of his prison-house, squeezed his small body through, and so escaped.

“Happen it’s as well,” thought the Master, watching the flying figure. Then, “Hi, Bob, lad!” he called; for the gray dog, ears back, tail streaming, was hurling down the slope after the fugitive.

On the bridge M’Adam turned, and, seeing his pursuer hot upon him, screamed, missed his footing, and fell with a loud splash into the stream—almost in that identical spot into which, years before, he had plunged voluntarily to save Red Wull.

On the bridge Owd Bob halted and looked down at the man struggling in the water below. He made a half move as though to leap in to the rescue of his enemy; then, seeing it was unnecessary, turned and trotted back to his master.

“Yo’ nob’but served him right, I’m thinkin’,” said the Master. “Like as not he came here wi’ the intent to mak’ an end to yo.’ Well, after Thursday, I pray God we’ll ha’ peace. It’s gettin’ above a joke.” The two turned back into the yard.

But down below them, along the edge of the stream, for the second time in this story, a little dripping figure was tottering homeward. The little man was crying—the hot tears mmgling on his cheeks with the undried waters of the Wastrel—crying with rage, mortification, weariness.

Cup Day.

It broke calm and beautiful, no cloud on the horizon, no threat of storm in the air; a fitting day on which the Shepherds’ Trophy must be won outright.

And well it was so. For never since the founding of the Dale Trials had such a concourse been gathered together on the North bank of the Silver Lea. From the Highlands they came; from the far Campbell country; from the Peak; from the county of many acres; from all along the silver fringes of the Soiway; assembling in that quiet corner of the earth to see the famous Gray Dog of Kenmuir fight his last great battle for the Shepherds’ Trophy.

By noon the gaunt Scaur looked down on such a gathering as it had never seen. The paddock at the back of the Dalesman’s Daughter was packed with a clammering, chattering multitude: animated groups of farmers; bevies of solid rustics; sharp-faced townsmen; loud-voiced bookmakers; giggling girls; amorous boys,—thrown together like toys in a sawdust bath; whilst here and there, on the outskirts of the crowd, a lonely man and wise-faced dog, come from afar to wrest his proud title from the best sheepdog in the North.

At the back of the enclosure was drawn up a formidale array of carts and carriages, varying as much in quality and character as did their owners. There was the squire’s landau rubbing axle-boxes with Jem Burton’s modest moke-cart; and there Viscount Birdsaye’s flaring barouche side by side with the red-wheeled wagon of Kenmuir.

In the latter, Maggie, sad and sweet in her simple summer garb, leant over to talk to Lady Eleanour; while golden-haired wee Anne, delighted with the surging crowd around, trotted about the wagon, waving to her friends, and shouting from very joyousness.

Thick as flies clustered that motley assembly on the north bank of the Silver Lea. While on the other side the stream was a little group of judges, inspecting the course.

The line laid out ran thus: the sheep must first be found in the big enclosure to the right of the starting flag; then up the slope and away from the spectators; around a flag and obliquely down the hill again; through a gap in the wall; along the hillside, parrallel to the Silver Lea; abruptly to the left through a pair of flags—the trickiest turn of them all; then down the slope to the pen, which was set up close to the bridge over the stream.

The proceedings began with the Local Stakes, won by Rob Saunderson’s veteran, Shep. There followed the Open Juveniles, carried off by Ned Hoppin’s young dog. It was late in the afternoon when, at length, the great event of the meeting was reached.

In the enclosure behind the Dalesman’s Daughter the clamor of the crowd increased tenfold, and the yells of the bookmakers were redoubled.

“Walk up, gen’lemen, walk up! the ole firm! Rasper? Yessir— twenty to one bar two! Twenty to one bar two! Bob? What price Bob? Even money, sir—no, not a penny longer, couldn’t do it! Red Wull? ‘oo says Red Wull?”

On the far side the stream is clustered about the starting flag the finest array of sheepdogs ever seen together.

“I’ve never seen such a field, and I’ve seen fifty,” is Parson Leggy’s verdict.

There, beside the tall form of his master, stands Owd Bob o’ Kenmuir, the observed of all. His silvery brush fans the air, and he holds his dark head high as he scans his challengers, proudly conscious that to-day will make or mar his fame. Below him, the meanlooking, smooth-coated black dog is the tinbeaten Pip, winner of the renowned Cambrian Stakes at Liangollen—as many think the best of all the good dogs that have come from sheep-dotted Wales. Beside him that handsome sable collie, with the tremendous coat. and slash of white on throat and face, is the famous MacCallum More, fresh from his victory at the Highland meeting. The cobby, brown dog, seeming of many breeds, is from the land o’ the Tykes—Merry, on whom the Yorkshiremen are laying as though they loved him. And Jess, the wiry black-and-tan, is the favorite of the men of of the Derwent and Dove. Tupper’s big blue Rasper is there; Londes-~ ley’s Lassie; and many more—too many t& mention: big and small, grand and mean, smooth and rough—and not a bad dog there.

And alone, his back to the others, stands a little bowed, conspicuous figure—Adam M’Adam; while the great dog beside him, a hideous incarnation of scowling defiance, is. Red Wull, the Terror o’ the Border.

The Tailless Tyke had already run up his. fighting colors. For MacCallum More, going up to examine this forlorn great adversary, had conceived for him a violent antip-. athy, and, straightway, had spun at him with all the fury of the Highland cateran, who at-~ tacks first and explains afterward. Red Wull, forthwith, had turned on him with savage, silent gluttony; bobtailed Rasper was racing up to join in the attack; and in another second the three would have been locked inseparably—but just in time M’Adam intervened. One of the judges came hurrying up.

“Mr. M’Adam,” he cried angrily. “if that brute of yours gets fighting again, hang me if I don’t disqualify him! Only last year at the Trials he killed the young Cossack dog.”

A dull flash of passion swept across M’Adam’s face. “Come here, Wullic!” he called. “Gin yon Hielant tyke attacks ye agin, ye’re to be disqualified.”

He was unheeded. The battle for the Cup had begun—little Pip leading the dance.

On the opposite slope the babel had subsided now. Hucksters left their wares, and bookmakers their stools, to watch the struggle. Every eye was intent on the moving figures of man and dog and three sheep over the stream.

One after one the competitors ran their course and penned their sheep—there was no single failure. And all received their just meed of applause, save only Adam M’Adam’s Red Wull.

Last of all, when Owd Bob trotted out to uphold his title, there went up such a shout as made Maggie’s wan cheeks to blush with pleasure, and wee Anne to scream right lustily.

His was an incomparable exhibition. Sheep should be humored rather than hurried; coaxed, rather than coerced. And that sheepdog has attained the summit of his art who subdues his own personality and leads his sheep in pretending to be led. Well might the bosoms of the Dalesmen swell with pride as they watched their favorite at his work; well might Tammas pull out that hackneyed phrase, “The brains of a mon and the way of a woman”; well might the crowd bawl their enthusiasm, and Long Kirby puff his cheeks and rattle the money in his trouser pockets.

But of this part it is enough to say that Pip, Owd Bob, and Red Wull were selected to fight out the struggle afresh.

The course was altered and stiffened. On the far side the stream it remained as before; up the slope; round a flag; down the hill again; through the gap in the wall; along the hillside; down through the two flags; turn; and to the stream again. But the pen was removed from its former position, carried over the bridge, up the near slope, and the hurdles put together at the very foot of the spectators.

The sheep had to be driven over the plank bridge, and the penning done beneath the very nose of the crowd. A stiff course, if ever there was one; and the time allowed, ten short minutes.

The spectators hustled and elbowed in their endeavors to obtain a good position. And well they might; for about to begin was the finest exhibition of sheep-handling any man there was ever to behold.

Those two, who had won on many a hard-fought field, worked together as they had never worked before. Smooth and swift, like a yacht in Southampton Water; round the flag, through the gap, they brought their sheep. Down between the two flags—accomplishing right well that awkward turn; and back to the bridge.

There they stopped: the sheep would not face that narrow way. Once, twice, and again, they broke; and each time the gallant little Pip, his tongue out and tail quivering, brought them back to the bridge-head.

At length one faced it; then another, and—it was too late. Time was up. The judges signalled; and the Welshman called off his dog and withdrew.

Out of sight of mortal eye, in a dip of the ground, Evan Jones sat down and took the small dark head between his

Comments (0)