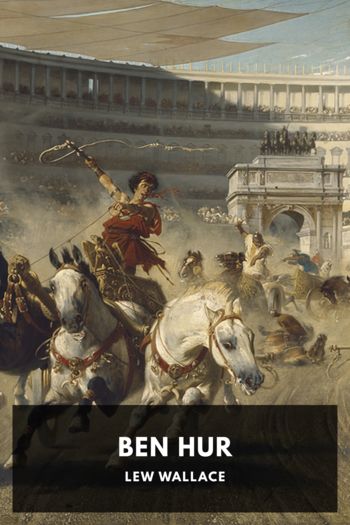

Ben Hur by Lew Wallace (best romance ebooks TXT) 📕

Description

Judah and Massala are close friends growing up, though one is Jewish and the other Roman. But when an accident happens after Massala returns from five years in Rome, Massala betrays his childhood friend and family. Judah’s mother and sister are taken away to prison, and he is sent to a galley-ship. Years later, Judah rescues a ship’s captain from drowning after a ship-to-ship battle, and the tribune adopts him in gratitude. Judah then devotes himself to learning as much as he can about being a warrior, in the hopes of leading an insurrection against Rome. He thinks he’s found the perfect leader in a young Nazarite, but is disappointed at the young man’s seeming lack of ambition.

Before writing Ben-Hur, Lew Wallace was best known for being a Major General in the American Civil War. After the war, a conversation with an atheist caused Wallace to take stock of how little he knew about his own religion. He launched into what would be years of research so that he could write with accuracy about first-century Israel. Although Judah Ben-Hur is the novel’s main character, the book’s subtitle, “A Tale of the Christ,” reveals Wallace’s real focus. Sales were only a trickle at the beginning, but it soon became a bestseller, and went on to become the best-selling novel of the nineteenth century. It has never been out of print, and to date has inspired two plays, a TV series, and five films—one of which, the 1959 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer epic, is considered to be one of the best films yet made.

Read free book «Ben Hur by Lew Wallace (best romance ebooks TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Lew Wallace

Read book online «Ben Hur by Lew Wallace (best romance ebooks TXT) 📕». Author - Lew Wallace

Others wagged their heads wisely, saying, “He would destroy the Temple, and rebuild it in three days, but cannot save himself.”

Others still: “He called himself the Son of God; let us see if God will have him.”

What all there is in prejudice no one has ever said. The Nazarene had never harmed the people; far the greater part of them had never seen him except in this his hour of calamity; yet—singular contrariety!—they loaded him with their curses, and gave their sympathy to the thieves.

The supernatural night, dropped thus from the heavens, affected Esther as it began to affect thousands of others braver and stronger.

“Let us go home,” she prayed—twice, three times—saying, “It is the frown of God, father. What other dreadful things may happen, who can tell? I am afraid.”

Simonides was obstinate. He said little, but was plainly under great excitement. Observing, about the end of the first hour, that the violence of the crowding up on the knoll was somewhat abated, at his suggestion the party advanced to take position nearer the crosses. Ben-Hur gave his arm to Balthasar; yet the Egyptian made the ascent with difficulty. From their new stand, the Nazarene was imperfectly visible, appearing to them not more than a dark suspended figure. They could hear him, however—hear his sighing, which showed an endurance or exhaustion greater than that of his fellow-sufferers; for they filled every lull in the noises with their groans and entreaties.

The second hour after the suspension passed like the first one. To the Nazarene they were hours of insult, provocation, and slow dying. He spoke but once in the time. Some women came and knelt at the foot of his cross. Among them he recognized his mother with the beloved disciple.

“Woman,” he said, raising his voice, “behold thy son!” And to the disciple, “Behold thy mother!”

The third hour came, and still the people surged round the hill, held to it by some strange attraction, with which, in probability, the night in midday had much to do. They were quieter than in the preceding hour; yet at intervals they could be heard off in the darkness shouting to each other, multitude calling unto multitude. It was noticeable, also, that coming now to the Nazarene, they approached his cross in silence, took the look in silence, and so departed. This change extended even to the guard, who so shortly before had cast lots for the clothes of the crucified; they stood with their officers a little apart, more watchful of the one convict than of the throngs coming and going. If he but breathed heavily, or tossed his head in a paroxysm of pain, they were instantly on the alert. Most marvellous of all, however, was the altered behavior of the high-priest and his following, the wise men who had assisted him in the trial in the night, and, in the victim’s face, kept place by him with zealous approval. When the darkness began to fall, they began to lose their confidence. There were among them many learned in astronomy, and familiar with the apparitions so terrible in those days to the masses; much of the knowledge was descended to them from their fathers far back; some of it had been brought away at the end of the Captivity; and the necessities of the Temple service kept it all bright. These closed together when the sun commenced to fade before their eyes, and the mountains and hills to recede; they drew together in a group around their pontiff, and debated what they saw. “The moon is at its full,” they said, with truth, “and this cannot be an eclipse.” Then, as no one could answer the question common with them all—as no one could account for the darkness, or for its occurrence at that particular time, in their secret hearts they associated it with the Nazarene, and yielded to an alarm which the long continuance of the phenomenon steadily increased. In their place behind the soldiers, they noted every word and motion of the Nazarene, and hung with fear upon his sighs, and talked in whispers. The man might be the Messiah, and then—But they would wait and see!

In the meantime Ben-Hur was not once visited by the old spirit. The perfect peace abode with him. He prayed simply that the end might be hastened. He knew the condition of Simonides’ mind—that he was hesitating on the verge of belief. He could see the massive face weighed down by solemn reflection. He noticed him casting inquiring glances at the sun, as seeking the cause of the darkness. Nor did he fail to notice the solicitude with which Esther clung to him, smothering her fears to accommodate his wishes.

“Be not afraid,” he heard him say to her; “but stay and watch with me. Thou mayst live twice the span of my life, and see nothing of human interest equal to this; and there may be revelations more. Let us stay to the close.”

When the third hour was about half gone, some men of the rudest class—wretches from the tombs about the city—came and stopped in front of the centre cross.

“This is he, the new King of the Jews,” said one of them.

The others cried, with laughter, “Hail, all hail, King of the Jews!”

Receiving no reply, they went closer.

“If thou be King of the Jews, or Son of God, come down,” they said, loudly.

At this, one of the thieves quit groaning, and called to the Nazarene, “Yes, if thou be Christ, save thyself and us.”

The people laughed and applauded; then, while they were listening for a reply, the other felon was heard to say to the first one, “Dost thou not fear God? We receive the due rewards of our deeds; but this man hath done nothing amiss.”

The bystanders were astonished; in the midst of the hush which ensued, the second felon spoke again, but this time to the Nazarene:

“Lord,” he said,

Comments (0)