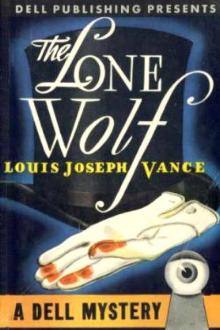

The Lone Wolf by Louis Joseph Vance (good ebook reader .txt) 📕

His pet superstition was that, as long as he refrained from practisinghis profession in Paris, Paris would remain his impregnable Tower ofRefuge. The world owed Bourke a living, or he so considered; and it mustbe allowed that he made collections on account with tolerable regularityand success; but Paris was tax-exempt as long as Paris offered himimmunity from molestation.

Not only did Paris suit his tastes excellently, but there was no place,in Bourke's esteem, comparable with Troyon's for peace and quiet.Hence, the continuity of his patronage was never broken by trials ofrival hostelries; and Troyon's was always expecting Bourke for thesimple reason that he invariably arrived unexpectedly, with neitherwarning nor ostentation, to stop as long as he liked, whether a day ora week or a month, and depart in the same manner.

His daily routine, as Troyon's came to know it, varied but slightly: hebreakf

Read free book «The Lone Wolf by Louis Joseph Vance (good ebook reader .txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Louis Joseph Vance

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Lone Wolf by Louis Joseph Vance (good ebook reader .txt) 📕». Author - Louis Joseph Vance

the midnight concert of those age-old timbers; and without mischance, at

length, they entered the main reception-hall, revealed by the dancing

spot-light as a room of noble proportions furnished with sombre

magnificence.

Here the girl was left alone for a few minutes, while Lanyard darted

above-stairs for a review of the state bedchambers and servants’

quarters.

With a sensation of being crushed and suffocated by the encompassing

dark mystery, she nerved herself against a protracted vigil. The

obscurity on every hand seemed alive with stealthy footfalls,

whisperings, murmurings, the passage of shrouded shapes of silence and

of menace. Her eyes ached, her throat and temples throbbed, her skin

crept, her scalp tingled. She seemed to hear a thousand different

noises of alarm. The only sounds she did not hear were

those—if any—that accompanied Lanyard’s departure and return. Had he

not been thoughtful enough, when a few feet distant, to give warning

with the light, she might well have greeted with a cry of fright the

consciousness of a presence near her: so silently he moved about. As it

was, she was startled, apprehensive of some misadventure, to find him

back so soon; for he hadn’t been gone three minutes.

“It’s quite all right,” he announced in hushed accents—no longer

whispering. “There are just five people in the house aside from

ourselves—all servants, asleep in the rear wing. We’ve got a clear

field—if no excuse for taking foolish chances! However, we’ll be

finished and off again in less than ten minutes. This way.”

That way led to a huge and gloomy library at one extreme of a chain of

great salons, a veritable treasure-gallery of exquisite furnishings and

authentic old masters. As they moved slowly through these chambers

Lanyard kept his flash-lamp busy; involuntarily, now and again, he

checked the girl before some splendid canvas or extraordinary antique.

“I’ve always meant to happen in some day with a moving-van and loot this

place properly!” he confessed with a little affected sigh. “Considered

from the viewpoint of an expert practitioner in my—ah—late profession,

it’s a sin and a shame to let all this go neglected, when it’s so

poorly guarded. The old lady—Madame Omber, you know—has all the money

there is, approximately, and when she dies all these beautiful things

go to the Louvre; for she’s without kith or kin.”

“But how did she manage to accumulate them all?” the girl wondered.

“It’s the work of generations of passionate collectors,” he explained.

“The late Monsieur Omber was the last of his dynasty; he and his

forebears brought together the paintings and the furniture; madame added

the Orientals gathered together by her first husband, and her own

collection of antique jewellery and precious stones—_her_ particular

fad….”

As he spoke the light of the flash-lamp was blotted out. An instant

later the girl heard a little clashing noise, of curtain rings sliding

along a pole; and this was thrice repeated.

Then, following another brief pause, a switch clicked; and streaming from

the hood of a portable desk-lamp, a pool of light flooded the heart of a

vast place of shadows, an apartment whose doors and windows alike were

cloaked with heavy draperies that hung from floor to ceiling in long and

shining folds. Immense black bookcases lined the walls, their shelves

crowded with volumes in rich bindings; from their tops pallid marble masks

peered down inquisitively, leering and scowling at the intruders. A huge

mantelpiece of carved marble, supporting a great, dark mirror, occupied

the best of one wall, beneath it a wide, deep fireplace yawned, partly

shielded by a screen of wrought brass and crystal. In the middle of the

room stood a library table of mahogany; huge leather chairs and couches

encumbered the remainder of its space. And the corner to the right of the

fireplace was shut off by a high Japanese screen of cinnabar and gold.

To this Lanyard moved confidently, carrying the lamp. Placing it on the

floor, he grasped one wing of the screen with both hands, and at cost of

considerable effort swung it aside, uncovering the face of a huge,

old-style safe built into the wall.

For several seconds—but not for many—Lanyard studied this problem

intently, standing quite motionless, his head lowered and thrust forward,

hands resting on his hips. Then turning, he nodded an invitation to draw

nearer.

“My last job,” he said with a smile oddly lighted by the lamp at his

feet—“and my easiest, I fancy. Sorry, too, for I’d rather have liked to

show off a bit. But this old-fashioned tin bank gives no excuse for

spectacular methods!”

“But,” the girl objected, “You’ve brought no tools!”

“Oh, but I have!” And fumbling in a pocket, Lanyard produced a pencil.

“Behold!” he laughed, brandishing it.

She knitted thoughtful brows: “I don’t understand.”

“All I need—except this.”

Crossing to the desk, he found a sheet of note-paper and, folding it,

returned.

“Now,” he said, “give me five minutes….”

Kneeling, he gave the combination-knob a smart preliminary twirl, then

rested a shoulder against the sheet of painted iron, his cheek to its

smooth, cold cheek, his ear close beside the dial; and with the

practised fingers of a master locksmith began to manipulate the knob.

Gently, tirelessly, to and fro he twisted, turned, raced, and checked

the combination, caressing it, humouring it, wheedling it, inexorably

questioning it in the dumb language his fingers spoke so deftly. And in

his ear the click and whir and thump of shifting wards and tumblers

murmured articulate response in the terms of their cryptic code.

Now and again, releasing the knob and sitting back on his heels, he

would bend intent scrutiny to the dial; note the position of the

combination, and with the pencil jot memoranda on the paper. This

happened perhaps a dozen times, at intervals of irregular duration.

He worked diligently, in a phase of concentration that apparently

excluded from his consciousness the near proximity of the girl, who

stood—or rather stooped, half-kneeling—less than a pace from his

shoulder, watching the process with interest hardly less keen than his

own.

Yet when one faint, odd sound broke the slumberous silence of the

salons, instantly he swung around and stood erect in a single movement,

gaze to the curtains.

But it had only been a premonitory rumble in the throat of a tall old

clock about to strike in the room beyond. And as its sonorous chimes

heralded two deep-toned strokes, Lanyard laughed quietly, intimately,

to the girl’s startled eyes, and sank back before the safe.

And now his task was nearly finished. Within another minute he sat back

with face aglow, uttered a hushed exclamation of satisfaction, studied

his memoranda for a space, then swiftly and with assured movements

threw the knob and dial into the several positions of the combination,

grasped the lever-handle, turned it smartly, and swung the door wide

open.

“Simple, eh?” he chuckled, with a glance aside to the girl’s eager face,

bewitchingly flushed and shadowed by the lamp’s up-thrown glow—“when

one knows the trick, of course! And now … if one were not an honest

man!”

A wave of his hand indicated the pigeonholes with which the body of the

safe was fitted: wide spaces and deep, stored tight with an

extraordinary array of leather jewel-cases, packets of stout paper

bound with tape and sealed, and boxes of wood and pasteboard of every

shape and size.

“They were only her finest pieces, her personal jewels, that Madame

Omber took with her to England,” he explained; “she’s mad about

them … never separated from them…. Perhaps the finest collection in

the world, for size and purity of water…. She had the heart to leave

these—all this!”

Lifting a hand he chose at random, dislodged two leather cases, placed

them on the floor, and with a blade of his penknife forced their

fastenings.

From the first the light smote radiance in blinding, coruscant welter.

Here was nothing but diamond jewellery, mostly in antique settings.

He took up a piece and offered it to the girl. She drew back her hand

involuntarily.

“No!” she protested in a whisper of fright.

“But just look!” he urged. “There’s no danger … and you’ll never see

the like of this again!”

Stubbornly she withheld her hand. “No, no!” she pleaded. “I—I’d rather

not touch it. Put it back. Let’s hurry. I—I’m frightened.”

He shrugged and replaced the jewel; then yielded again to impulse of

curiosity and lifted the lid of the second case.

It contained nothing but pieces set with coloured stones of the first

order—emeralds, amethysts, sapphires, rubies, topaz, garnets,

lapis-lazuli, jacinthes, jades, fashioned by master-craftsmen into

rings, bracelets, chains, brooches, lockets, necklaces, of exquisite

design: the whole thrown heedlessly together, without order or care.

For a moment the adventurer stared down soberly at this priceless hoard,

his eyes narrowing, his breathing perceptibly quickened. Then with a

slow gesture, he reclosed the case, took from his pocket that other

which he had brought from London, opened it, and held it aside beneath

the light, for the girl’s inspection.

He looked not once either at its contents or at her, fearing lest his

countenance betray the truth, that he had not yet succeeded completely

in exorcising that mutinous and rebellious spirit, the Lone Wolf, from

the tenement over which it had so long held sway; and content with the

sound of her quick, startled sigh of amaze that what she now beheld

could so marvellously outshine what had been disclosed by the other

boxes, he withdrew it, shut it, found it a place in the safe, and

without pause closed the door, shot the bolts, and twirled the dial

until the tumblers fairly sang.

One final twist of the lever-handle convincing him that the combination

was effectively dislocated, he rose, picked up the lamp, replaced it on

the desk with scrupulous care to leave no sign that it had been moved,

and looked round to the girl.

She was where he had left her, a small, tense, vibrant figure among the

shadows, her eyes dark pools of wonder in a face of blazing pallor.

With a high head and his shoulders well back he made a gesture

signifying more eloquently than any words: “All that is ended!”

“And now…?” she asked breathlessly.

“Now for our get-away,” he replied with assumed lightness. “Before

dawn we must be out of Paris…. Two minutes, while I straighten this

place up and leave it as I found it.”

He moved back to the safe, restored the wing of the screen to the spot

from which he had moved it, and after an instant’s close examination of

the rug, began to explore his pockets.

“What are you looking for?” the girl enquired.

“My memoranda of the combination—”

“I have it.” She indicated its place in a pocket of her coat. “You left

it on the floor, and I was afraid you might forget—”

“No fear!” he laughed. “No”—as she offered him the folded paper—“keep

it and destroy it, once we’re out of this. Now those porti�res…”

Extinguishing the desk-light, he turned attention to the draperies at

doors and windows….

Within five minutes, they were once more in the silent streets of Passy.

They had to walk as far as the Trocad�ro before Lanyard found a fiacre,

which he later dismissed at the corner in the Faubourg St. Germain.

Another brief walk brought them to a gate in the garden wall of a

residence at the junction of two quiet streets.

“This, I think, ends our Parisian wanderings,” Lanyard announced. “If

you’ll be good enough to keep an eye out for busybodies—and yourself

as inconspicuous

Comments (0)