Psychology by Robert S. Woodworth (top rated ebook readers .TXT) 📕

[Footnote: A series of waggish critics has evolved the following: "First psychology lost its soul, then it lost its mind, then it lost consciousness; it still has behavior, of a kind."]

The best way of getting a true picture of psychology, and of reaching an adequate definition of its subject-matter, would be to inspect the actual work of psychologists, so as to see what kind of knowledge they are seeking. Such a survey would reveal quite a variety of problems under process of investigation, some of them practical problems, others not directly practical.

Varieties of Psychology

Differential psychology.

One line of question that always interests the beginner in psychology is as to how people differ--how different people act under the same circumstances--and why; and if we watch the professional psychologist, we often find him working at just this problem. He tests a great number of individuals to see how they

Read free book «Psychology by Robert S. Woodworth (top rated ebook readers .TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Robert S. Woodworth

- Performer: -

Read book online «Psychology by Robert S. Woodworth (top rated ebook readers .TXT) 📕». Author - Robert S. Woodworth

The runner on the mark, "set" for a quick start, is a perfect picture of preparedness. Here the onlookers can see the preparation, since the ready signal has aroused visible muscular response in the shape of a crouching position. It is not simple crouching, but "crouching to spring." But if the onlookers imagine themselves to be seeing the whole preparation--if they suppose the preparation to be simply an affair of the muscles--they overlook the established fact that the muscles are held in action by the nerve centers, and would relax instantly if the nerve centers should stop acting. The preparation is neural more than muscular. The neural apparatus is set to respond to the pistol shot by strong discharge into the leg muscles.

What the animal psychologists have called the delayed reaction is a very instructive example of preparation. An animal is placed before a row of three food boxes, all looking just alike, two of them, however, being locked while the third is unlocked. Sometimes one is unlocked and sometimes another, and the one which at any time is unlocked is designated by an electric bulb lighted above the door. The animal is first trained to go to whichever box shows the light; he always gets food from the lighted box. When he has thoroughly learned to respond in this way, the "delayed reaction" experiment begins. Now the animal is held while the light is burning, and only released a certain time after the light is out, and the question is whether, after this delay, he will still follow the signal and go straight to the right door. It is found that he will do so, provided the delay is not too long--how long depends on the animal. With rats the delay cannot exceed 5 seconds, with cats it can reach 18 {77} seconds, with dogs 1 to 3 minutes, with children (in a similar test) it increased from 20 seconds at the age of fifteen months to 50 seconds at two and a half years, and to 20 minutes or more at the age of five years.

Rats and cats, in this experiment, need to keep their heads or bodies turned towards the designated box during the interval between the signal and the release; or else lose their orientation. Some dogs, however, and children generally, can shift their position and still, through some inner orientation, react correctly when released. The point of the experiment is that the light signal puts the animal or child into a state tending towards a certain result, and that, when that result is not immediately attainable, the state persists for a time and produces results a little later.

Preparatory ReactionsIn the delayed reaction, the inner orientation does little during the interval before the final reaction, except to maintain a readiness for making that reaction; but often "preparatory reactions" occur before the final reaction can take place. Suppose you whistle for your dog when he is some distance off and out of sight. You give one loud whistle and wait. Presently the dog swings around the corner and dashes up to you. Now, what kept the dog running towards you after your whistle had ceased and before he caught sight of you? Evidently he was directed towards the end-result of reaching you, and this directing tendency governed his movements during the process. He made many preparatory reactions on the way to his final reaction of jumping up on you; and these preparatory reactions were, of course, responses to the particular trees he had to dodge, and the ditches he had to jump; but they were at the same time governed by the inner state set up in him by your {78 } whistle. This inner state favored certain reactions and excluded others that would have occurred if the dog had not been in a hurry. He passed another dog on the way without so much as saying, "How d'ye do?" And he responded to a fence by leaping over it, instead of trotting around through the gate. That is to say, the inner state set up in him by your whistle facilitated reactions that were preparatory to the final reaction, and inhibited reactions that were not in that line.

A hunting dog following the trail furnishes another good example of a directive tendency. Give a bloodhound the scent of a particular man and he will follow that scent persistently, not turning aside to respond to stimuli that would otherwise influence him, nor even to follow the scent of another man. Evidently an inner neural adjustment has been set up in him predisposing him to respond to a certain stimulus and not to others.

The homing of the carrier pigeon is a good instance of activity directed in part by an inner adjustment, since, when released at a distance from home, he is evidently "set" to get back home, and often persists and reaches home after a very long flight. Or, take the parallel case of the terns, birds which nest on a little island not far from Key West. Of ten birds taken from their nests and transported on shipboard out into the middle of the Gulf of Mexico and released 500 miles from home, eight reappeared at their nests after intervals varying from four to eight days. How they found their way over the open sea remains a mystery, but one thing is clear: they persisted in a certain line of activity until a certain end-result was reached, on which this line of activity ceased.

One characteristic of tendencies that has not previously been mentioned comes out in this example. When a tendency has been aroused, the animal (or man) is tense and {79} restless till the goal has been reached, and then quiets down. The animal may or may not be clearly conscious of the goal, but he is restless till the goal has been attained, and his restlessness then ceases. In terms of behavior, what we see is a series of actions which continues till a certain result has been reached and then gives way to rest. Introspectively, what we feel (apart from any clear mental picture of the goal) is a restlessness and tenseness during a series of acts, giving way to relief and satisfaction when a certain result has been reached.

A hungry or thirsty animal is restless; he seeks food or drink, which means that he is making a series of preparatory reactions, which continues till food or drink has been found, and terminates in the end-reaction of eating or drinking.

What the Preparatory Reactions AccomplishThe behavior of a hungry or thirsty individual is worth some further attention--for it is the business of psychology to interest itself in the most commonplace happenings, to wonder about things that usually pass for matters of course, and, if not to find "sermons in stones", to derive high instruction from very lowly forms of animal behavior. Now, what is hunger? Fundamentally an organic state; next, a sensation produced by this organic state acting on the internal sensory nerves, and through them arousing in the nerve centers an adjustment or tendency towards a certain end-reaction, namely, eating. Now, I ask you, if hunger is a stimulus to the eating movements, why does not the hungry individual eat at once? Why, at least, does he not go through the motions of eating? You say, because he has nothing to eat. But he could still make the movements; there is no physical impossibility in his making chewing and swallowing movements without the presence of food. {80} Speaking rationally, you perhaps say that he does not make these movements because he sees they would be of no use without food to chew; but this explanation would scarcely apply to the lower sorts of animal, and besides, you do not have to check your jaws by any such rational considerations. They simply do not start to chew except when food is in the mouth. Well, then, you say, chewing is a response to the presence of food in the mouth; and taking food into the mouth is a response to the stimulus of actually present food. The response does not occur unless the stimulus is present; that is simple.

Not quite so simple, either. Unless one is hungry, the presence of food does not arouse the feeding reaction; and even food actually present in the mouth will be spewed out instead of chewed and swallowed, if one is already satiated. Try to get a baby to take more from his bottle than he wants! Eating only occurs when one is both hungry and in the presence of food. Two conditions must be met: the internal state of hunger and the external stimulus of food; then, and then only, will the eating reaction take place.

Hunger, though a tendency to eat, does not arouse the eating movements while the stimulus of present food is lacking; but, for all that, hunger does arouse immediate action. It typically arouses the preparatory reactions of seeking food. Any such reaction is at the same time a response to some actually present stimulus. Just as the dog coming at your whistle was responding every instant of his progress to some particular object--leaping fences, dodging trees--so the dog aroused to action by the pangs of hunger begins at once to respond to present objects. He does not start to eat them, because they are not the sort of stimuli that produce this response, but he responds by dodging them or finding his way by them in his quest for food. The responses that the hungry dog makes to other objects than {81} food are preparatory reactions, and these, if successful, put the dog in the presence of food. That is to say, the preparatory reactions provide the stimulus that is necessary to arouse the end-reaction. They bring the individual to the stimulus, or the stimulus to the individual.

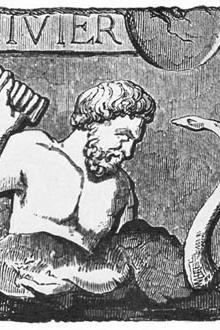

Fig. 23.--A stimulus arouses the tendency towards the end-reaction, R, but (as indicated by the dotted line), T is not by itself sufficient to arouse R; but T can and does arouse P, a preparatory reaction, and P (or some external result directly produced by P), coöperating with T, gives rise to R.

What we can say about the modus operandi of hunger, then, amounts to this: Hunger is an inner state and adjustment predisposing the individual to make eating movements in response to the stimulus of present food; in the absence of food, hunger predisposes to such other responses to various stimuli as will bring the food stimulus into play, and thus complete the conditions necessary for the eating reaction. In general, an aroused reaction-tendency predisposes the individual to make a certain end-reaction when the proper stimulus for that reaction is present; otherwise, it predisposes him to respond to other stimuli, which are present, by preparatory reactions that eventually bring to bear on the individual the stimulus required to arouse the end-reaction.

Let us apply our formula to one more simple case. While reading in the late afternoon, I find the daylight growing dim, rise and turn on the electric light. The stimulus that sets this series of acts going is the dim light; the first, inner response is a need for light. This need tends, by force of habit, to make me turn the button, but it does not make me execute this movement in the air. I only make this movement when the button is in reaching distance. My first {82}

Comments (0)