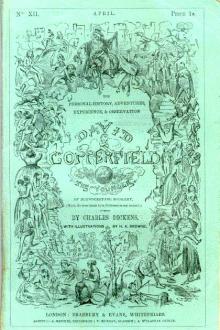

Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕

People have often wondered how Dickens found time to accomplish so many different things. One of the secrets of this, no doubt, was his love of order. He was the most systematic of men. Everything he did "went like clockwork," and he prided himself on his punctuality. He could not work in a room unless everything in it was in its proper place. As a consequence of this habit of regularity, he never wasted time.

The work of editorship was very pleasant to Dickens, and scarcely three years after his leaving the Daily News he began the publication of a new magazine which he called Household Words. His aim was to make it cheerful, useful and at the same time cheap, so that the poor could afford to buy it as well as the rich. His own sto

Read free book «Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: -

Read book online «Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕». Author - Charles Dickens

His heartless uncle, the Marquis de St. Evrémonde, in France, the head of the family, hated the young man for this noble spirit. It was this uncle who had invented the plot to accuse his nephew of treason. He had hired a dishonest spy known as Barsad, who swore he had found papers in Darnay's trunk that proved his guilt, and, as Darnay had been often back and forth to France on family matters, the case looked dark for him.

Cruelly enough, among those who were called to the trial as witnesses, to show that Darnay had made these frequent journeys to France, were Doctor Manette and Lucie—because they had seen him on the boat during that memorable crossing. Lucie's tears fell fast as she gave her testimony, believing him innocent and knowing that her words would be used to condemn him.

Darnay would doubtless have been convicted but for a curious coincidence: A dissipated young lawyer, named Sydney Carton, sitting in the court room, had noticed with surprise that he himself looked very much like the prisoner; in fact, that they were so much alike they might almost have been taken for twin brothers. He called the attention of Darnay's lawyer to this, and the latter—while one of the witnesses against Darnay was making oath that he had seen him in a certain place in France—made Carton take off his wig (all lawyers wear wigs in England while in court) and stand up beside Darnay. The two were so alike the witness was puzzled, and he could not swear which of the two he had seen. For this reason Darnay, to Lucie's great joy, was found not guilty.

Sydney Carton, who had thought of and suggested this clever thing, was a reckless, besotted young man. He cared for nobody, and nobody, he used to say, cared for him. He lacked energy and ambition to work and struggle for himself, but for the sake of plenty of money with which to buy liquor, he studied cases for another lawyer, who was fast growing rich by his labor. His master, who hired him, was the lion; Carton was content, through his own indolence and lack of purpose, to be the jackal.

His conscience had always condemned him for this, and now, as he saw the innocent Darnay's look, noble and straightforward, so like himself as he might have been, and as he thought of Lucie's sweet face and of how she had wept as she was forced to give testimony against the other, Carton felt that he almost hated the man whose life he had saved.

The trial brought Lucie and these two men (so like each other in feature, yet so unlike in character) together, and afterward they often met at Doctor Manette's house.

It was in a quiet part of London that Lucie and her father lived, all alone save for the faithful Miss Pross. They had little furniture, for they were quite poor, but Lucie made the most of everything. Doctor Manette had recovered his mind, but not all of his memory. Sometimes he would get up in the night and walk up and down, up and down, for hours. At such times Lucie would hurry to him and walk up and down with him till he was calm again. She never knew why he did this, but she came to believe he was trying vainly to remember all that had happened in those lost years which he had forgotten. He kept his prison bench and tools always by him, but as time went on he gradually used them less and less often.

Mr. Lorry, with his flaxen wig and constant smile, came to tea every Sunday with them and helped to keep Doctor Manette cheerful. Sometimes Darnay, Sydney Carton and Mr. Lorry would meet there together, but of them all, Darnay came oftenest, and soon it was easy to see that he was in love with Lucie.

Sydney Carton, too, was in love with her, but he was perfectly aware that he was quite undeserving, and that Lucie could never love him in return. She was the last dream of his wild, careless life, the life he had wasted and thrown away. Once he told her this, and said that, although he could never be anything to her himself, he would give his life gladly to save any one who was near and dear to her.

Lucie fell in love with Darnay at length and one day they were married and went away on their wedding journey.

Until then, since his rescue, Lucie had never been out of Doctor Manette's sight. Now, though he was glad for her happiness, yet he felt the pain of the separation so keenly that it unhinged his mind again. Miss Pross and Mr. Lorry found him next morning making shoes at the old prison bench and for nine days he did not know them at all. At last, however, he recovered, and then, lest the sight of it affect him, one day when he was not there they chopped the bench to pieces and burned it up.

But her father was better after Lucie came back with her husband, and they took up their quiet life again. Darnay loved Lucie devotedly. He supported himself still by teaching. Mr. Lorry came from the bank oftener to tea and Sydney Carton more rarely, and their life was peaceful and content.

Once after his marriage, his cruel uncle, the Marquis de St. Evrémonde, sent for Darnay to come to France on family matters. Darnay went, but declined to remain or to do the other's bidding.

But his uncle's evil life was soon to be ended. While Darnay was there the marquis was murdered one night in his bed by a grief-crazed laborer, whose little child his carriage had run over.

Darnay returned to England, shocked and horrified the more at the indifference of the life led by his race in France. Although now, by the death of his uncle, he had himself become the Marquis de St. Evrémonde, yet he would not lay claim to the title, and left all the estates in charge of one of the house servants, an honest steward named Gabelle.

He had intended after his return to Lucie to settle all these affairs and to dispose of the property, which he felt it wrong for him to hold; but in the peace and happiness of his life in England he put it off and did nothing further.

And this neglect of Darnay's—as important things neglected are apt to prove—came before long to be the cause of terrible misfortune and agony to them all.

IIDARNAY CAUGHT IN THE NET

While these things were happening in London, the one city of this tale, other very different events were occurring in the other city of the story—Paris, the French capital.

The indifference and harsh oppression of the court and the nobles toward the poor had gone on increasing day by day, and day by day the latter had grown more sullen and resentful. All the while the downtrodden people of Paris were plotting secretly to rise in rebellion, kill the king and queen and all the nobles, seize their riches and govern France themselves.

The center of this plotting was Defarge, the keeper of the wine shop, who had cared for Doctor Manette when he had first been released from prison. Defarge and those he trusted met and planned often in the very room where Mr. Lorry and Lucie had found her father making shoes. They kept a record of all acts of cruelty toward the poor committed by the nobility, determining that, when they themselves should be strong enough, those thus guilty should be killed, their fine houses burned, and all their descendants put to death, so that not even their names should remain in France. This was a wicked and awful determination, but these poor, wretched people had been made to suffer all their lives, and their parents before them, and centuries of oppression had killed all their pity and made them as fierce as wild beasts that only wait for their cages to be opened to destroy all in their path.

They were afraid, of course, to keep any written list of persons whom they had thus condemned, so Madame Defarge, the wife of the wine seller, used to knit the names in fine stitches into a long piece of knitting that she seemed always at work on.

Madame Defarge was a stout woman with big coarse hands and eyes that never seemed to look at any one, yet saw everything that happened. She was as strong as a man and every one was somewhat afraid of her. She was even crueler and more resolute than her husband. She would sit knitting all day long in the dirty wine shop, watching and listening, and knitting in the names of people whom she hoped soon to see killed.

One of the hated names that she knitted over and over again was "Evrémonde." The laborer who, in the madness of his grief for his dead child, had murdered the Marquis de St. Evrémonde, Darnay's hard-hearted uncle, had been caught and hanged; and, because of this, Defarge and his wife and the other plotters had condemned all of the name of Evrémonde to death.

Meanwhile the king and queen of France and all their gay and careless court of nobles feasted and danced as heedlessly as ever. They did not see the storm rising. The bitter taxes still went on. The wine shop of Defarge looked as peaceful as ever, but the men who drank there now were dreaming of murder and revenge. And the half-starved women, who sat and looked on as the gilded coaches of the rich rolled through the streets, were sullenly waiting—watching Madame Defarge as she silently knitted, knitted into her work names of those whom the people had condemned to death without mercy.

One day this frightful human storm, which for so many years had been gathering in France, burst over Paris. The poor people rose by thousands, seized whatever weapons they could get—guns, axes, or even stones of the street—and, led by Defarge and his tigerish wife, set out to avenge their wrongs. Their rage turned first of all against the Bastille, the old stone prison in which so many of their kind had died, where Doctor Manette for eighteen years had made shoes. They beat down the thick walls and butchered the soldiers who defended it, and released the prisoners. And wherever they saw one of the king's uniforms they hanged the wearer to the nearest lamp post. It was the beginning of the terrible Revolution in France that was to end in the murder of thousands of innocent lives. It was the beginning of a time when Paris's streets were to run with blood, when all the worst passions of the people were loosed, and when they went mad with the joy of revenge.

The storm spread over France—to the village where stood the great château of the Evrémonde family, and the peasants set fire to it and burned it to the ground. And Gabelle (the servant who had been left in charge by Darnay,

Comments (0)