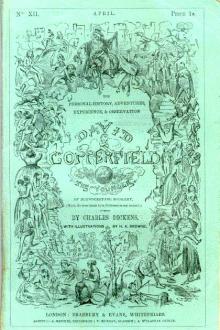

Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕

People have often wondered how Dickens found time to accomplish so many different things. One of the secrets of this, no doubt, was his love of order. He was the most systematic of men. Everything he did "went like clockwork," and he prided himself on his punctuality. He could not work in a room unless everything in it was in its proper place. As a consequence of this habit of regularity, he never wasted time.

The work of editorship was very pleasant to Dickens, and scarcely three years after his leaving the Daily News he began the publication of a new magazine which he called Household Words. His aim was to make it cheerful, useful and at the same time cheap, so that the poor could afford to buy it as well as the rich. His own sto

Read free book «Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: -

Read book online «Tales from Dickens by Charles Dickens (books you need to read TXT) 📕». Author - Charles Dickens

She had suffered much without complaint, but Harthouse's proposal had been the last straw. Added to all the insults she had suffered at her husband's hands, and her fearful suspicion of Tom's guilt, it had proven too much for her to bear. She had pretended to agree to Harthouse's plan only that she might the more quickly rid herself of his presence.

Mr. Gradgrind, astonished at her sudden arrival at Stone Lodge, was shocked no less at her ghastly appearance than by what she said. She told him she cursed the hour when she had been born to grow up a victim to his teachings; that her whole life had been empty; that every hope, affection and fancy had been crushed from her very infancy and her better angel made a demon. She told him the whole truth about her marriage to Bounderby—that she had married him solely for the advancement of Tom, the only one she had ever loved—and that now she could no longer live with her husband or bear the life she had made for herself.

And when she had said this, Louisa, the daughter his "system" had brought to such despair, fell at his feet.

At her pitiful tale the tender heart that Mr. Gradgrind had buried in his long-past youth under his mountain of facts stirred again and began to beat. The mountain crumbled away, and he saw in an instant, as by a lightning flash, that the plan of life to which he had so rigidly held was a complete and hideous failure. He had thought there was but one wisdom, that of the head; he knew at last that there was a deeper wisdom of the heart also, which all these years he had denied!

When she came to herself, Louisa found her father sitting by her bedside. His face looked worn and older. He told her he realized at last his life mistake and bitterly reproached himself. Sissy, too, was there, her love shining like a beautiful light on the other's darkness. She knelt beside the bed and laid the weary head on her breast, and then for the first time Louisa burst into sobs.

Next day Sissy sought out Harthouse, who was waiting, full of sulky impatience at the failure of Louisa to appear as he had expected. Sissy told him plainly what had occurred, and that he should never see Louisa again. Harthouse, realizing that his plan had failed, suddenly discovered that he had a great liking for camels, and left the same hour for Egypt, never to return to Coketown.

It was while Sissy was absent on this errand of her own that the furious Bounderby and the triumphant Mrs. Sparsit, the latter voiceless and still sneezing, appeared at Stone Lodge.

Mr. Gradgrind took the mill owner greatly aback with the statement that Louisa had had no intention whatever of eloping and was then in that same house and under his care. Angry and blustering at being made such a fool of, Bounderby turned on Mrs. Sparsit, but in her disappointment at finding it a mistake, she had dissolved in tears. When Mr. Gradgrind told him he had concluded it would be better for Louisa to remain for some time there with him, Bounderby flew into a still greater rage and stamped off, swearing his wife should come home by noon next day or not at all.

To be sure Louisa did not go, and next day Bounderby sent her clothes to Mr. Gradgrind, advertised his country house for sale, and, needing something to take his spite out upon, redoubled his efforts to find the robber of the bank.

And he began by covering the town with printed placards, offering a large regard for the arrest of Stephen Blackpool.

IVSTEPHEN'S RETURN

Rachel had known, of course, of the rumors against Stephen, and had been both indignant and sorrowful. She alone knew where he was, and how to find him, for deeming it impossible, because of his trouble with the Coketown workmen, to get work under his own name, he had taken another.

Now that he was directly charged with the crime, she wrote him the news at once, so that he might lose no time in returning to face the unjust accusation. Being so certain herself of his innocence, she made no secret of what she had done, and all Coketown waited, wondering whether he would appear or not.

Two days passed and he had not come, and then Rachel told Bounderby the address to which she had written him. Messengers were sent, who came back with the report that Stephen had received her letter and had left at once, saying he was going to Coketown, where he should long since have arrived.

Another day with no Stephen, and now almost every one believed he was guilty, had taken Rachel's letter as a warning and had fled. All the while Tom waited nervously, biting his nails and with fevered lips, knowing that Stephen, when he came, would tell the real reason why he had loitered near the bank, and so point suspicion to himself.

On the third day Mrs. Sparsit saw a chance to distinguish herself. She recognized on the street "Mrs. Pegler," the old countrywoman who also had been suspected. She seized her and, regardless of her entreaties, dragged her to Bounderby's house and into his dining-room, with a curious crowd flocking at their heels.

She plumed herself on catching one of the robbers, but what was her astonishment when the old woman called Bounderby her dear son, pleading that her coming to his house was not her fault and begging him not to be angry even if people did know at last that she was his mother.

Mr. Gradgrind, who was present when they entered, having always heard Bounderby tell such dreadful tales of his bringing-up, reproached her for deserting her boy in his infancy to a drunken grandmother. At this the old woman nearly burst with indignation, calling on Bounderby himself to tell how false this was and how she had pinched and denied herself for him till he had begun to be successful.

Everybody laughed at this, for now the true story of the bullying mill owner's tales was out. Bounderby, who had turned very red, was the only one who did not seem to enjoy the scene. After he had wrathfully shut every one else from the house, he vented his anger on Mrs. Sparsit for meddling (as he called it) with his own family affairs. He ended by giving her the wages due her and inviting her to take herself off at once.

So Mrs. Sparsit, for all her cap-setting and spying, had to leave her comfortable nest and go to live in a poor lodging as companion to the most grudging, peevish, tormenting one of her noble relatives, an invalid with a lame leg.

But meanwhile another day had passed—the fourth since Rachel had sent her letter—and still Stephen had not come. On this day, full of her trouble, Rachel had wandered with Sissy, now her fast friend, some distance out of the town, through some fields where mining had once been carried on.

Suddenly she cried out—she had picked up a hat and inside it was the name "Stephen Blackpool." An instant later a scream broke from her lips that echoed over the country-side. Before them, at their very feet, half-hidden by rubbish and grasses, yawned the ragged mouth of a dark, abandoned shaft. That instant both Rachel and Sissy guessed the truth—that Stephen, returning, had not seen the chasm in the darkness, and had fallen into its depths.

They ran and roused the town. Crowds came from Coketown. Rope and windlass were brought and two men were lowered into the pit. The poor fellow was there, alive but terribly injured. A rough bed was made, and so at last the crushed and broken form was brought up to the light and air.

A surgeon was at hand with wine and medicines, but it was too late. Stephen spoke with Rachel first, then called Mr. Gradgrind to him and asked him to clear the blemish from his name. He told him simply that he could do so through his son Tom. This was all. He died while they bore him home, holding the hand of Rachel, whom he loved.

Stephen's last words had told the truth to Mr. Gradgrind. He read in them that his own son was the robber. Tom's guilty glance had seen also. With suspicion removed from Stephen, he felt his own final arrest sure.

Sissy noted Tom's pale face and trembling limbs. Guessing that he would attempt flight too late, and longing to save the heartbroken father from the shame of seeing his son's arrest and imprisonment, she drew the shaking thief aside and in a whisper bade him go at once to Sleary, the proprietor of the circus to which her father had once belonged. She told him where the circus was to be found at that season of the year, and bade him ask Sleary to hide him for her sake till she came. Tom obeyed. He disappeared that night, and later Sissy told his father what she had done.

Mr. Gradgrind, with Sissy and Louisa, followed as soon as possible, intending to get his son to the nearest seaport and so out of the country on a vessel, for he knew that soon he himself, Tom's father, would be questioned and obliged to tell the truth. They traveled all night, and at length reached the town where the circus showed.

Sleary, for Sissy's sake, had provided Tom with a disguise in which not even his father recognized him. He had blacked his sullen face and dressed him in a moth-eaten greatcoat and a mad cocked hat, in which attire he played the role of a black servant in the performance. Tom met them, grimy and defiant, ashamed to meet Louisa's eyes, brazen to his father, anxious only to be saved from his deserved punishment.

A seaport was but three hours away. He was soon dressed and plans for his departure were completed. But at the last moment danger appeared. It came in the person of the porter of Bounderby's bank, who had all along suspected Tom. He had watched the Gradgrind house, followed its master when he left and now laid hands on Tom, vowing he would take him back to Coketown.

In this moment of the father's despair, Sleary the showman saved the day for the shivering thief. He agreed with the porter that as Tom was guilty of a crime he must certainly go with him, and he offered, moreover, to drive the captor and his prisoner at once to the nearest railroad station. He winked at Sissy as he proposed this, and she was not alarmed. The porter accepted the proposal at once, but he did not guess what the showman had in mind.

Sleary's horse was an educated horse. At a certain word from its owner it would stop and begin to dance, and would not budge from the spot till he gave the command in a particular way. He had an educated dog, also, that would do anything it was told. With this horse hitched to the carriage and this dog trotting innocently behind, the showman set off with the porter and Tom, while Mr. Gradgrind and Louisa, whom Sissy had told to trust in Sleary, waited all night for his return.

It was morning before Sleary came back, with the news that Tom was undoubtedly safe from pursuit, if not already aboard ship. He told them how, at the word from him, the educated horse had begun to dance; how Tom had slipped down and got away, while the educated dog, at his command, had penned the frightened porter in the carriage all night, fearing to stir.

Thus Tom,

Comments (0)