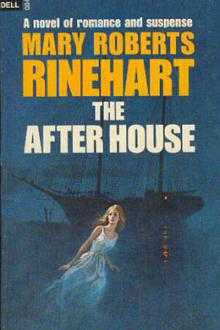

The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕

McWhirter it was who got me my berth on the Ella. It must have been about the 20th of July, for the Ella sailed on the 28th. I was strong enough to leave the hospital, but not yet physically able for any prolonged exertion. McWhirter, who was short and stout, had been alternately flirting with the nurse, as she moved in and out preparing my room for the night, and sizing me up through narrowed eyes.

"No," he said, evidently following a private line of thought; "you don't belong behind a counter, Leslie. I'm darned if I think you belong in the medical profession, either. The British army'd suit you."

"The - what?"

"You know - Kipling ide

Read free book «The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Mary Roberts Rinehart

- Performer: -

Read book online «The After House by Mary Roberts Rinehart (dark books to read TXT) 📕». Author - Mary Roberts Rinehart

I told of the long nights without sleep, while, with our few available men, we tried to work the Ella back to land; of guarding the after house; of a hundred false alarms that set our nerves quivering and our hearts leaping. And I made them feel, I think, the horror of a situation where each man suspected his neighbor, feared and loathed him, and yet stayed close by him because a known danger is better than an unknown horror.

The record of my examination is particularly faulty, McWhirter having allowed personal feeling to interfere with accuracy. Here and there in the margins of his notebook I find unflattering allusions to the prosecuting attorney; and after one question, an impeachment of my motives, to which Mac took violent exception, no answer at all is recorded, and in a furious scrawl is written: “The little whippersnapper! Leslie could smash him between his thumb and finger!”

I found another curious record - a leaf, torn out of the book, and evidently designed to be sent to me, but failing its destination, was as follows: “For Heaven’s sake, don’t look at the girl so much! The newspaper men are on.”

But, to resume my examination. The first questions were not of particular interest. Then:

“Did the prisoner know you had moved to the after house?”

“I do not know. The forecastle hands knew.”

“Tell what you know of the quarrel on July 31 between Captain Richardson and the prisoner.”

“I saw it from a deck window.” I described it in detail.

“Why did you move to the after house?”

“At the request of Mrs. Johns. She said she was nervous.”

“What reason did she give?”

“That Mr. Turner was in a dangerous mood; he had quarreled with the captain and was quarreling with Mr. Vail.”

“Did you know the arrangement of rooms in the after house? How the people slept?”

“In a general way.”

“What do you mean by that?”

“I knew Mr. Vail’s room and Miss Lee’s.”

“Did you know where the maids slept?”

“Yes.”

“You have testified that you were locked in. Was the key kept in the lock?”

“Yes.”

“Would whoever locked you in have had only to move the key from one side of the door to the other?”

“Yes.”

“Was the key left in the lock when you were fastened in?”

“No.”

“Now, Dr. Leslie, we want you to tell us what the prisoner did that night when you told him what had happened.”

“I called to him to come below, for God’s sake. He seemed dazed and at a loss to know what to do. I told him to get his revolver and call the captain. He went into the forward house and got his revolver, but he did not call the captain. We went below and stumbled over the captain’s body.”

“What was the mate’s condition?”

“When we found the body?”

“His general condition.”

“He was intoxicated. He collapsed on the steps when we found the captain. We both almost collapsed.”

“What was his mental condition?”

“If you mean, was he frightened, we both were.”

“Was he pale?”

“I did not notice then. He was pale and looked ill later, when the crew had gathered.”

“About this key: was it ever found? The key to the storeroom?”

“Yes.”

“When?”

“That same morning.”

“Where? And by whom?”

“Miss Lee found it on the floor in Mr. Turner’s room.”

The prosecution was totally unprepared for this reply, and proceedings were delayed for a moment while the attorneys consulted. On the resumption of my examination, they made a desperate attempt to impeach my character as a witness, trying to show that I had sailed under false pretenses; that I was so feared in the after house that the women refused to allow me below, or to administer to Mr. Turner the remedies I prepared; and, finally, that I had surrendered myself to the crew as a suspect, of my own accord.

Against this the cross-examination threw all its weight. The prosecuting attorneys having dropped the question of the key, the shrewd young lawyer for the defense followed it up: -

“This key, Dr. Leslie, do you know where it is now?”

“Yes; I have it.”

“Will you tell how it came into your possession?”

“Certainly. I picked it up on the deck, a night or so after the murders. Miss Lee had dropped it.” I caught Elsa Lee’s eye, and she gave me a warm glance of gratitude.

“Have you the key with you?”

“Yes.” I produced it.

“Are you a football player, Doctor?”

“I was.”

“I thought I recalled you. I have seen you play several times. In spite of our friend the attorney for the commonwealth, I do not believe we will need to call character witnesses for you. Did you see Miss Lee pick up the key to the storeroom in Mr. Turner’s room?”

“Yes.”

“Did it occur to you at the time that the key had any significance?”

“I wondered how it got there.”

“You say you listened inside the locked door, and heard no sound, but felt a board rise up under your knee. A moment or two later, when you called the prisoner, he was intoxicated, and reeled. Do you mean to tell us that a drunken man could have made his way in the darkness, through a cabin filled with chairs tables, and a piano, in absolute silence?”

The prosecuting attorney was on his feet in an instant, and the objection was sustained. I was next shown the keys, club, and file taken from Singleton’s mattress. “You have identified these objects as having been found concealed in the prisoner’s mattress. Do any of these keys fit the captain’s cabin?”

“No.”

“Who saw the prisoner during the days he was locked in his cabin?”

“I saw him occasionally. The cook saw him when he carried him his meals.”

“Did you ever tell the prisoner where the axe was kept?”

“No.”

“Did the members of the crew know?”

“I believe so. Yes.”

“Was the fact that Burns carried the key to the captain’s cabin a matter of general knowledge?”

“No. The crew knew that Burns and I carried the keys; they did not know which one each carried, unless -”

“Go on, please.”

“If any one had seen Burns take Mrs. Johns forward and show her the axe, he would have known.”

“Who were on deck at that time?”

“All the crew were on deck, the forecastle being closed. In the crow’s-nest was McNamara; Jones was at the wheel.”

“From the crow’s-nest could the lookout have seen Burns and Mrs. Johns going forward?”

“No. The two houses were connected by an awning.”

“What could the helmsman see?”

“Nothing forward of the after house.”

The prosecution closed its case with me. The defense, having virtually conducted its case by cross-examination of the witnesses already called, contented itself with-producing a few character witnesses, and “rested.” Goldstein made an eloquent plea of “no case,” and asked the judge so to instruct the jury.

This was refused, and the case went to the jury on the seventh day - a surprisingly short trial, considering the magnitude of the crimes.

The jury disagreed. But, while they wrangled, McWhirter and I were already on the right track. At the very hour that the jurymen were being discharged and steps taken for a retrial, we had the murderer locked in my room in a cheap lodging-house off Chestnut Street.

With the submission of the case to the jury, the witnesses were given their freedom. McWhirter had taken a room for me for a day or two to give me time to look about; and, his own leave of absence from his hospital being for ten days, we had some time together.

My situation was better than it had been in the summer. I had my strength again, although the long confinement had told on me. But my position was precarious enough. I had my pay from the Ella, and nothing else. And McWhirter, with a monthly stipend from his hospital of twenty-five dollars, was not much better off.

My first evening of freedom we spent at the theater. We bought the best seats in the house, and we dressed for the occasion - being in the position of having nothing to wear between shabby everyday wear and evening clothes.

“It is by way of celebration,” Mac said, as he put a dab of shoe-blacking over a hole in his sock; “you having been restored to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That’s the game, Leslie - the pursuit of happiness.”

I was busy with a dress tie that I had washed and dried by pasting it on a mirror, an old trick of mine when funds ran low. I was trying to enter into Mac’s festive humor, but I had not reacted yet from the horrors of the past few months.

“Happiness!” I said scornfully. “Do you call this happiness?”

He put up the blacking, and, coming to me, stood eyeing me in the mirror as I arranged my necktie.

“Don’t be bitter,” he said. “Happiness was my word. The Good Man was good to you when he made you. That ought to be a source of satisfaction. And as for the girl -”

“What girl?”

“If she could only see you now. Why in thunder didn’t you take those clothes on board? I wanted you to. Couldn’t a captain wear a dress suit on special occasions?”

“Mac,” I said gravely, “if you will think a moment, you will remember that the only special occasions on the Ella, after I took charge, were funerals. Have you sat through seven days of horrors without realizing that?”

Mac had once gone to Europe on a liner, and, having exhausted his funds, returned on a cattle-boat.

“All the captains I ever knew,” he said largely, “were a fussy lot - dressed to kill, and navigating the boat from the head of a dinner-table. But I suppose you know. I was only regretting that she hadn’t seen you the way you’re looking now. That’s all. I suppose I may regret, without hurting your feelings!”

He dropped all mention of Elsa after that, for a long time. But I saw him looking at me, at intervals, during the evening, and sighing. He was still regretting!

We enjoyed the theater, after all, with the pent-up enthusiasm of long months of work and strain. We laughed at the puerile fun, encored the prettiest of the girls, and swaggered in the lobby between acts, with cigarettes. There we ran across the one man I knew in Philadelphia, and had supper after the play with three or four fellows who, on hearing my story, persisted in believing that I had sailed on the Ella as a lark or to follow a girl. My simple statement that I had done it out of necessity met with roars of laughter and finally I let it go at that.

It was after one when we got back to the lodging-house, being escorted there in a racing car by a riotous crowd that stood outside the door, as I fumbled for my key, and screeched in unison: “Leslie! Leslie! Leslie! Sic ‘em!” before they drove away.

The light in the dingy lodging-house parlor was burning full, but the hall was dark. I stopped inside and lighted a cigarette.

“Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, Mac!” I said. “I’ve got the first two, and

Comments (0)