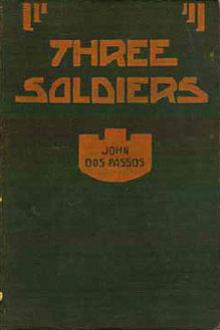

Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos (books to read to be successful txt) 📕

A sharp voice beside his cot woke him with a jerk.

"Get up, you."

The white beam of a pocket searchlight was glaring in the face of the man next to him.

"The O. D." said Fuselli to himself.

"Get up, you," came the sharp voice again.

The man in the next cot stirred and opened his eyes.

"Get up."

"Here, sir," muttered the man in the next cot, his eyes blinking sleepily in the glare of the flashlight. He got out of bed and stood unsteadily at attention.

"Don't you know better than to sleep in your O. D. shirt? Take it off."

"Yes, sir."

"What's your name?"

The man looked up, blinking, too dazed to

Read free book «Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos (books to read to be successful txt) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: John Dos Passos

- Performer: -

Read book online «Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos (books to read to be successful txt) 📕». Author - John Dos Passos

“Madame Boncour.”

“Of course. You must know everybody…. It’s so small.”

“And you’re going to stay here a long time?”

“Almost forever, and work, and talk to you; may I use your piano now and then?”

“How wonderful!”

Genevieve Rod jumped to her feet. Then she stood looking at him, leaning against one of the twisted stems of the vines, so that the broad leaves fluttered about her face, A white cloud, bright as silver, covered the sun, so that the hairy young leaves and the wind-blown grass of the lawn took on a silvery sheen. Two white butterflies fluttered for a second about the arbor.

“You must always dress like that,” she said after a while.

Andrews laughed.

“A little cleaner, I hope,” he said. “But there can’t be much change. I have no other clothes and ridiculously little money.”

“Who cares for money?” cried Genevieve. Andrews fancied he detected a slight affectation in her tone, but he drove the idea from his mind immediately.

“I wonder if there is a farm round here where I could get work.”

“But you couldn’t do the work of a farm labourer,” cried Genevieve, laughing.

“You just watch me.”

“It’ll spoil your hands for the piano.”

“I don’t care about that; but all that’s later, much later. Before anything else I must finish a thing I am working on. There is a theme that came to me when I was first in the army, when I was washing windows at the training camp.”

“How funny you are, Jean! Oh, it’s lovely to have you about again. But you’re awfully solemn today. Perhaps it’s because I made you kiss me.”

“But, Genevieve, it’s not in one day that you can unbend a slave’s back, but with you, in this wonderful place…. Oh, I’ve never seen such sappy richness of vegetation! And think of it, a week’s walking first across those grey rolling uplands, and then at Blois down into the haze of richness of the Loire…. D’you know Vendome? I came by a funny little town from Vendome to Blois. You see, my feet…. And what wonderful cold baths I’ve had on the sand banks of the Loire…. No, after a while the rhythm of legs all being made the same length on drill fields, the hopeless caged dullness will be buried deep in me by the gorgeousness of this world of yours!”

He got to his feet and crushed a leaf softly between his fingers.

“You see, the little grapes are already forming…. Look up there,” she said as she brushed the leaves aside just above his head. “These grapes here are the earliest; but I must show you my domain, and my cousins and the hen yard and everything.”

She took his hand and pulled him out of the arbor. They ran like children, hand in hand, round the box-bordered paths.

“What I mean is this,” he stammered, following her across the lawn. “If I could once manage to express all that misery in music, I could shove it far down into my memory. I should be free to live my own existence, in the midst of this carnival of summer.”

At the house she turned to him; “You see the very battered ladies over the door,” she said. “They are said to be by a pupil of Jean Goujon.”

“They fit wonderfully in the landscape, don’t they? Did I ever tell you about the sculptures in the hospital where I was when I was wounded?”

“No, but I want you to look at the house now. See, that’s the tower; all that’s left of the old building. I live there, and right under the roof there’s a haunted room I used to be terribly afraid of. I’m still afraid of it…. You see this Henri Quatre part of the house was just a fourth of the house as planned. This lawn would have been the court. We dug up foundations where the roses are. There are all sorts of traditions as to why the house was never finished.”

“You must tell me them.”

“I shall later; but now you must come and meet my aunt and my cousins.”

“Please, not just now, Genevieve…. I don’t feel like talking to anyone except you. I have so much to talk to you about.”

“But it’s nearly lunch time, Jean. We can have all that after lunch.”

“No, I can’t talk to anyone else now. I must go and clean myself up a little anyway.”

“Just as you like…. But you must come this afternoon and play to us. Two or three people are coming to tea…. It would be very sweet of you, if you’d play to us, Jean.”

“But can’t you understand? I can’t see you with other people now.”

“Just as you like,” said Genevieve, flushing, her hand on the iron latch of the door.

“Can’t I come to see you tomorrow morning? Then I shall feel more like meeting people, after talking to you a long while. You see, I….” He paused, with his eyes on the ground. Then he burst out in a low, passionate voice: “Oh, if I could only get it out of my mind…those tramping feet, those voices shouting orders.”

His hand trembled when he put it in Genevieve’s hand. She looked in his eyes calmly with her wide brown eyes.

“How strange you are today, Jean! Anyway, come back early tomorrow.”

She went in the door. He walked round the house, through the carriage gate, and went off with long strides down the road along the river that led under linden trees to the village.

Thoughts swarmed teasingly through his head, like wasps about a rotting fruit. So at last he had seen Genevieve, and had held her in his arms and kissed her. And that was all. His plans for the future had never gone beyond that point. He hardly knew what he had expected, but in all the sunny days of walking, in all the furtive days in Paris, he had thought of nothing else. He would see Genevieve and tell her all about himself; he would unroll his life like a scroll before her eyes. Together they would piece together the future. A sudden terror took possession of him. She had failed him. Floods of denial seethed through his mind. It was that he had expected so much; he had expected her to understand him without explanation, instinctively. He had told her nothing. He had not even told her he was a deserter. What was it that had kept him from telling her? Puzzle as he would, he could not formulate it. Only, far within him, the certainty lay like an icy weight: she had failed him. He was alone. What a fool he had been to build his whole life on a chance of sympathy? No. It was rather this morbid playing at phrases that was at fault. He was like a touchy old maid, thinking imaginary results. “Take life at its face value,” he kept telling himself. They loved each other anyway, somehow; it did not matter how. And he was free to work. Wasn’t that enough?

But how could he wait until tomorrow to see her, to tell her everything, to break down all the silly little barriers between them, so that they might look directly into each other’s lives?

The road turned inland from the river between garden walls at the entrance to the village. Through half-open doors Andrews got glimpses of neatly-cultivated kitchen-gardens and orchards where silver-leaved boughs swayed against the sky. Then the road swerved again into the village, crowded into a narrow paved street by the white and cream-colored houses with green or grey shutters and pale, red-tiled roofs. At the end, stained golden with lichen, the mauve-grey tower of the church held up its bells against the sky in a belfry of broad pointed arches. In front of the church Andrews turned down a little lane towards the river again, to come out in a moment on a quay shaded by skinny acacia trees. On the corner house, a ramshackle house with roofs and gables projecting in all directions, was a sign: “Rendezvous de la Marine.” The room he stepped into was so low, Andrews had to stoop under the heavy brown beams as he crossed it. Stairs went up from a door behind a worn billiard table in the corner. Mme. Boncour stood between Andrews and the stairs. She was a flabby, elderly woman with round eyes and a round, very red face and a curious smirk about the lips.

“Monsieur payera un petit peu d’advance, n’est-ce pas, Monsieur?”

“All right,” said Andrews, reaching for his pocketbook. “Shall I pay you a week in advance?”

The woman smiled broadly.

“Si Monsieur desire…. It’s that life is so dear nowadays. Poor people like us can barely get along.”

“I know that only too well,” said Andrews.

“Monsieur est etranger….” began the woman in a wheedling tone, when she had received the money.

“Yes. I was only demobilized a short time ago.”

“Aha! Monsieur est demobilise. Monsieur remplira la petite feuille pour la police, n’est-ce pas?”

The woman brought from behind her back a hand that held a narrow printed slip.

“All right. I’ll fill it out now,” said Andrews, his heart thumping.

Without thinking what he was doing, he put the paper on the edge of the billiard table and wrote: “John Brown, aged 23. Chicago Ill., Etats-Unis. Musician. Holder of passport No. 1,432,286.”

“Merci, Monsieur. A bientot, Monsieur. Au revoir, Monsieur.”

The woman’s singing voice followed him up the rickety stairs to his room. It was only when he had closed the door that he remembered that he had put down for a passport number his army number. “And why did I write John Brown as a name?” he asked himself.

“John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave, But his soul goes marching on. Glory, glory, hallelujah! But his soul goes marching on.”

He heard the song so vividly that he thought for an instant someone must be standing beside him singing it. He went to the window and ran his hand through his hair. Outside the Loire rambled in great loops towards the blue distance, silvery reach upon silvery reach, with here and there the broad gleam of a sand bank. Opposite were poplars and fields patched in various greens rising to hills tufted with dense shadowy groves. On the bare summit of the highest hill a windmill waved lazy arms against the marbled sky.

Gradually John Andrews felt the silvery quiet settle about him. He pulled a sausage and a piece of bread out of the pocket of his coat, took a long swig of water from the pitcher on his washstand, and settled himself at the table before the window in front of a pile of ruled sheets of music paper. He nibbled the bread and the sausage meditatively for a long while, then wrote “Arbeit und Rhythmus” in a large careful hand at the top of the paper. After that he looked out of the window without moving, watching the plumed clouds sail like huge slow ships against the slate-blue sky. Suddenly he scratched out what he had written and scrawled above it: “The Body and Soul of John Brown.” He got to his feet and walked about the room with clenched hands.

“How curious that I should have written that name. How curious that I should have written that name!” he said aloud.

He sat down at the table again and forgot everything in the music that possessed him.

The next morning he walked out early along the river, trying to occupy himself until it should be time to go to see Genevieve. The memory of his first days in the army, spent washing windows at the training camp, was very vivid in his mind.

Comments (0)