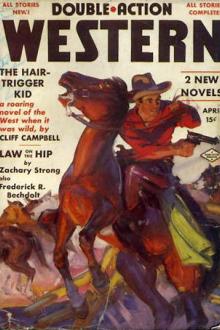

The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕

"The curtain ain't up," said the sheriff, "but I reckon that the stage is set and that they's gunna be an entrance pretty pronto."

"Here's somebody coming," said Georgia, gesturing toward the farther end of the street.

"Yeah," said the sheriff, "but he's comin' too slow to mean anything."

"Slow and earnest wins the race," said another.

They were growing impatient; like a crowd at a bullfight, when the entrance of the matador is delayed too long.

"We're wasting the day," said Milman to his family. "That's a long ride ahead of us."

"Don't go now," said Georgia. "I've got a tingle in my finger tips that says something is going to happen."

Other voices were rising, jesting, laughing, when some one called out something at the farther end of the veranda, and instantly there was a wave of silence that spread upon them all.

"What is it?" whispered Milman to the sheriff.

"Shut up!" said the sheriff. "They say th

Read free book «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕». Author - Max Brand

“Put back that thing!” groaned Deacon.

“Put it back, Bud,” said the Kid.

Bud, almost unwillingly, obeyed.

“Now, who sent you, man?”

“Shay,” said Deacon.

He dropped into a chair.

He was almost fainting, and his head fell back, his body shook

convulsively.

“I thought so,” said the Kid. “Shay has a sort of reason for wanting me.

Shay offered ten thousand, did he?”

“Aye, he did.”

“I’m glad to know it. I’m glad to know that he has that much spare cash.

Why didn’t you bring Dixon along?”

This startled Deacon erect in the chair again.

“Who told you that?” he cried.

“About Dixon, you mean?”

“Yes, about Dixon. What sneaking crook has been spilling news on us all?”

“I can guess, Deacon,” said the Kid. “I know that he’s with Shay, and

that this sort of a job is just about his size.”

“He wouldn’t horn in,” said Deacon, bewildered by the answer. “He said

that his luck was bad, today, so far as you went. I dunno why he said

that, but he’s a superstitious kind—. and by Heaven, they’s something in

his superstition, too. I’ve seen what luck a man can have with you today,

Kid!”

He glowered as he spoke.

“That’s about all,” said the Kid. “I don’t need you any longer.”

Deacon stood up.

“It’s to be a bullet in the back, I reckon?” said he.

“Did I ever shoot a man through the back?” asked the Kid. “You’re one to

learn, though. You mean that I’m free to go?”

“I told you that I’d turn you loose, for the sake of the news that you

could give me.”

“You mean it, Kid?”

“I mean it. Get out, Deacon.”

Deacon went slowly to the door. There he paused and turned, at last. “I

dunno that I make you out, Kid,” said he. “You must have underground

wires all over the world. What made you know that Harbridge wasn’t behind

this? He hates you enough, and he’s got the money to hire men.”

“Harbridge generally does his own killing,” said the Kid. “And after all,

it was only a guess, Deacon. Just a bluff, but it seems to have worked.”

The face of Deacon wrinkled with hatred and with anger.

“I ain’t fit to wear long trousers,” said he. “I been bluffed all the way

through. You got anything else to say?”

“Yes,” said the Kid, “I have a little message for Shay. Will you take it

to him, word for word?”

“Aye.”

“Tell him that one of these days I’ll call when I can find him at home

and not in a hurry to leave. Tell him another thing. If any of his rats

come here to make trouble for the Trainors, Dad and Ma, I mean, I’ll

never sleep on the trail until it takes me to them. And I’ll never rest

till I’ve got Shay. Tell him if he so much as breathes on their

windowpane, I’ll burn him alive with—a song and dance. I’ll hire

Indians to do a good job on him. That goes for the old folks. As for Bud,

of course, he takes his chance with me. The open season is on for Bud and

me, as far as Shay is concerned. That goes without saying. Now get out of

here, Deacon, and the next time you see me, don’t stop to ask questions.

Fill your hand, even if it’s in church!”

Deacon gave him one backward, glowering look, then glided through the

door, and a moment afterward, they heard the sound of his horse, as it

departed at a dogtrot across the valley.

It left the two inside free to face one another.

“Kid,” said Bud Trainor huskily, “I dunno that I got much to say to you.”

“You can thank me for putting a lot of bad men on your trail, Bud,” said

the other.

“Them?” said Bud. He smiled, and waved his hand. “I’ll take my chances

with them! But you, Kid—what made you do it?”

“Do what?”

“Talk as though—as though I was your partner?”

“Well, Bud, are you happy here at home?”

“Here? I’d rather be in prison.”

“The open trail is not a prison. Why not come along—as my partner?”

“I’d rather than anything on—. But hold on. You know what I am, Kid. I

ain’t worthy of—”

“Hush up,” said the Kid, smiling. “I’ll take my chances. Shall we shake

on it?”

Bud Trainor suddenly bowed his head. He fumbled vaguely before him, but

the strong right hand of the Kid found his, and closed like gentle iron

upon it. The compact was sealed.

Two days after this, “Spot” Gregory of the Milman ranch daubed his rope

on a tough Roman-nosed broncho in the corral, and started out to teach

the brute manners. That big-headed mustang bounced up and down between

the sky and the hard ground until Spot’s teeth were loose in his head.

After ten minutes the gelding decided that its luck was out, and settled

down to a good, steady lope going along with pricking ears, quite

good-naturedly.

This sign did not altogether deceive Spot Gregory. He knew all about

horses, and pricking ears are apt to mean forethought as much as good

nature; so when a mustang thinks ahead, it is likely to think of trouble.

Therefore, the foreman of the Milman ranch was not at all surprised when,

on climbing over the hills toward Hurry Creek, on the first down slope,

the Roman-nose began to pitch once more.

It is ten times as hard for a horse to pitch on a down slope as on the

level—but if it manages the feat, it is a hundred times harder for the

rider to stick in the saddle. Spot Gregory, nearly flipped out of place

in the first ten seconds, settled down to give that broncho a busting

that would last him the rest of his days, but in the midst of

accomplishing the good work, scratching the pony fore-and-aft and

flogging it thoroughly with the cruel quirt, he became aware of an odd

condition in the valley before him.

For the edges of Hurry Creek were rimmed and lined with cattle which were

not going down to drink, but remained up on the hills, redeyed with

thirst.

Spot Gregory rubbed his eyes and looked again.

Hurry Creek was to the Milman ranch what the heart’s blood is to the

human body. In the whole length and breadth of the big place, there was

not a drop of water except for the creek. Sometimes during periods of

heavy rain, little rivulets formed in the hollows, but they were not

worth thinking about. There was any quantity of the finest grass on the

ranch. The woodlands were a small fortune, also. But of water, there was

only this one vein.

It was enough!

When Milman’s old father came here, long years before, he had had wit

enough to pick out the place with forethought and locate with care.

All through its upper course, Hurry Creek went shouting and raving

through a high-walled canyon. On still days the noise of its anger

drifted far away to the ranch house, like a faint prophecy of trouble. At

a certain point, leaving the canyon, it spread out suddenly through an

almost level tract of rolling land, and then dropped into the opposite

hills through another high-sided trench. Cows could not get up or down

the walls of either the higher or the lower ravine, but they did not need

to. The Milman ranch was in outline like a huge dumb-bell. The narrow

grip was where the waters of Hurry Creek ran from canyon to canyon across

the rolling ground. The huge knobs were the wide-spreading acres,

thousands upon thousands, which formed what they called the western and

the eastern ranches. And, from the farthest corners of the two districts,

the cattle would march into the creek for water.

The younger ones usually went in every day. The older stock often

remained away two or three days in the best grazing at the edges of the

far hill and then would come at a trot or a lope the long distance to the

stream. There, standing belly-deep, they drank and drank to repletion.

They waded back to shore and browsed a little on the short grasses which

were always eaten close. Then they would drink again, and begin a

leisurely trip back to the chosen eating places.

But on this morning the thirsty legions did not go down to drink. Some

were lying down on the upper edges of the valley. Some wandered back and

forth uneasily. A few milled and lowed frantically close by the water’s

edge. Sometimes, singly or in groups, they made dashes for the bright

promise of the water, but they were always turned away by certain riders

who careened up and down either bank of the stream, whirling lariats,

shouting, running the cows off to a distance, where the animals turned in

despair and looked hopelessly back toward the creek.

There were enough men to ride herd in this arduous manner both east and

west of the creek. On the eastern side, moreover, farthest from Spot at

this moment, appeared several wagons. Smoke rose from a camp fire, here,

and one of the wagons, being partially unloaded, showed on the ground a

heap of what looked like thick coils of newly burnished silver.

Spot could guess its true nature; it was barbed wire!

In the brush beside the water, other men were cutting stakes of a

sufficient length, and beginning at the mouth of the northern canyon, on

each side of it, two small groups were setting up the posts and stringing

the wires upon them. Anger darkened the eyes of Spot Gregory until the

whole scene disappeared before him in a swirl of black. He blinked and

looked again, half hoping that the vision would disappear like a bad

dream.

It did not disappear. It grew more and more vivid.

The early sun, now breaking through its veil of morning mist, made the

whole view clearer to him. The men, little with distance, toiled on

unceasingly. Behind them, on the new-made fences, the barbed wire gleamed

like spider threads, bright with dew, and up and down the open bank of

the creek, the watchful riders wheeled and flashed upon their active

horses.

He tried to count all heads, and numbered sixteen, besides those who

might be out of sight around the wagons, or who perhaps were otherwise

concealed from him.

How they had come in was plainly to be seen. The tracks of the wagons

stretched away toward the south, on the eastern side of the creek. No

doubt they had worked the heavily laden wagons, up through the high hills

to a place of advantage, and when they were ready, they had simply driven

down in the middle of the night. Now they were busy in pushing ahead

their lines of battle, for a battle certainly would be fought for the

possession of those streaks of barbed wire.

Grinding his teeth, he calculated chances.

He had under him a number of good men on that ranch. They could ride like

fiends, and when it came to shooting, they were more than average. He

could rake together as many fighting men as were present in the hollow,

there, beneath him. He could recruit still other hands in the

neighborhood.

But even if he had

Comments (0)