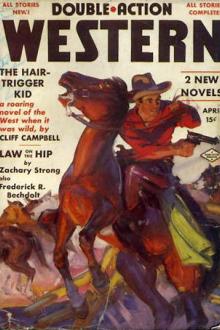

The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕

"The curtain ain't up," said the sheriff, "but I reckon that the stage is set and that they's gunna be an entrance pretty pronto."

"Here's somebody coming," said Georgia, gesturing toward the farther end of the street.

"Yeah," said the sheriff, "but he's comin' too slow to mean anything."

"Slow and earnest wins the race," said another.

They were growing impatient; like a crowd at a bullfight, when the entrance of the matador is delayed too long.

"We're wasting the day," said Milman to his family. "That's a long ride ahead of us."

"Don't go now," said Georgia. "I've got a tingle in my finger tips that says something is going to happen."

Other voices were rising, jesting, laughing, when some one called out something at the farther end of the veranda, and instantly there was a wave of silence that spread upon them all.

"What is it?" whispered Milman to the sheriff.

"Shut up!" said the sheriff. "They say th

Read free book «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕». Author - Max Brand

“Pretty nigh,” said Dad Trainor. “He’s been buyin’ up and buyin’ up all

the time. Them that have enough money is like stones rollin’ downhill.

The longer they live, the faster they go. He’s gunna own most of the

countryside around here, before long. They’s trouble ahead for him!”

“Because he is so rich?”

“A rich man with a pretty daughter is like a gent smeared with honey,

when they’s wasps flyin’ in the air, on a hot August afternoon. Pretty

soon he’s gunna get stung bad, I can tell you! Stung right to the bone,

so’s he’ll ache good and plenty.”

“I’ve seen her,” said the Kid, looking ‘aimlessly across the night.

He seemed to begin to forget the alarm which he had been feeling the

moment before.

“Scout out there and see if there’s anything moving,” he said to Davey.

“Get close to the ground, and look at the sky line, will you?”

“Sure!” said Davey, delighted, and he bounded away.

“What are you suspicionin’ about?” asked Dad Trainor suddenly.

“Oh, I don’t know,” answered the Kid. “You never know. In a way, I’m the

honey that attracts a kind of wasp, too. The humming of them, Dad, is a

thing that has waked me up in the night, a good many times.”

“If you got any doubts,” said Dad Trainor, “you wouldn’t be sendin’ out a

wee kid like that one, would you? Kind of half town raised, too! If I

could have him out here all the time, his eyes and ears would sharpen up,

maybe.”

“They’re sharp enough,” said the Kid, easily. “If so much as a partridge

whirs within a mile of him, he’ll hear it and he’ll see ft. I’ll trust

Davey. He knows how to look at a man in the clay, and he’ll know how to

look for a man in the night. My bet is on Davey.”

“Well, he’s a good lad,” said Dad Trainor. “Bright and quick, and I gotta

say that town livin’ ain’t made his fists soft. The tannin’ that he give

to little Harry Michaels one-two year back, it was a beauty. He handed

Harry a ten-pound handicap and a lickin’ that was worth watchin’. But

still, if they’s any doubt about what’s out there in the dark of the

valley—”

“There’s always doubt, Dad,” said the younger man. “But if a fellow has

nightmares by day as well as by night, what’s the use of living at all, I

say.”

“Aye, and a true thing that is,” said Dad. “Them that takes chances and

changes horses is them that makes the round trip through life, and the

rest of us, we just travel along one road and never see nothin’—but

dust!”

He shook his head violently, and led the way on toward the house. They

only stopped outside to give the mare a nose bag of barley, and then they

went into the little shack where Ma Trainor greeted them with a smile and

a face shining with the steam of cookery. She declared that she had some

sour-milk biscuits in that oven that would warm the heart of any man in

the world. In the meantime the stove enriched the air with a multitude of

vapors, while the Kid went over to lift lids, sniff contents, and discuss

the properest ways of seasoning and baking in a Dutch oven. In these

matters, Mrs. Trainor was a mint of information.

“Where you been keepin’ yourself, Kid?” she said.

“A little bit of all around,” said he. “But mostly south. What What have

you been thinking since I last saw you?”

She accepted the question with a smile.

“Mostly tasting the first part of my life over again,” said she. “That’s

what you do when you get my age, Kid. Them biscuits oughta be ready now.

Kick that dog off that chair and sit down. Where’s them other two?”

There was only one small lamp, the chimney slightly yellowed with smoke,

and when this was placed on the table and the glass still further

obscured with the steam of the food, it gave the room new dimensions, and

a sort of gloomy dignity. In the corner, the ladder which led to the

garret now climbed quite out of sight. As the food was piled on the

table, which sagged a little to one side even under this light weight,

the missing two now came in.

“I met Bud,” said Davey, “and he told me that he’d already scouted

around.”

“Yeah,” said Bud, rather gloomily. “When I heard that hoss nicker, I just

took a look around, but it ain’t nothin’ but one of the Milman cayuses up

there on the bluff. Them Milmans, it ain’t no wonder that they lose a lot

of stock by rustlers. They go and shove their hosses and cows right down

your throat, sort of.”

“A loose horse, eh?” asked the Kid.

“Yeah, a loose horse.”

“I’m glad to know that. I thought that one hadn’t whinnied himself out at

the finish.”

“Can you tell when a hoss has had his fill up of neighin’?” demanded Bud,

somewhat sulkily.

“Pretty close,” replied the Kid. “There’s something about the way that he

tunes up at the start that can tell you whether he’s going to wheeze,

snort, cough, or squeal at the finish.”

“Well, I never could read the mind of a hoss that close,” said Bud.

“Throw me a coupla them biscuits, will ya?”

The Kid, silently, passed the plate, and while Bud helped himself, the

eye of the Kid lingered for a moment, thoughtfully, upon the gloomy face.

He shifted his glance, then, over his shoulder toward the door and seemed

for an instant uneasy, but in a moment shrugged his shoulders and settled

himself to his meal.

He had begun a little story of Yucatan in which the very steam of the

jungle of that southland appeared, when, into the doorway behind him,

stepped two men, silent as shadows. The Kid had his back fairly turned,

but something made him stiffen as though he actually had seen the naked

guns in their hands, leveled upon him.

But, little Davey, who hardly had been able to shift his eyes from his

hero, up to this moment, now slowly rose like a ghost from his stool.

“Jimmy!” he breathed.

“Jus’ take it quiet,” said a voice from the doorway.

“Aye, take it slow and easy, Kid,” said the second man. “And give a jury

a chance at you!”

The kid rested his elbows upon the edge of the table.

“You wouldn’t object if I was to stretch my arms—so long as I stretched

‘em up?” he asked.

“Leave ‘em be. Leave ‘em still. We know you, Kid. It ain’t where your

hands are that counts. It’s the way that you can move ‘em. Watch him

now!”

“Heck! Ain’t I watchin’ till my eyes ache?” said the other. “Go up and

fan him for his armory. I’ll keep him covered.”

Old Dad Trainor had recovered from his stupor and had risen again.

“What’s the meanin’ of this, boys?” he demanded.

“Why,” said the Kid, “it’s just two old friends of mine dropped in for a

little call. It’s Sam Deacon and Lefty Morgan. How’s everything, Deacon?”

“Right now,” said Deacon, “it’s pretty good. I reckon I can tell how good

things is with you, though.”

“You, Morgan and Deacon,” said Dad Trainor. “What kind of jamboree d’you

reckon that this here is, anyway? You ain’t gunna do nothin’ to the Kid,

in my house!”

“Ain’t we?” asked Morgan.

He had come well into the dull circle of the light, showing a

death’s-head, all bones, scantly covered with a tight-drawn parchment

skin. His teeth were so prominent that the pale lips constantly grinned

back from them, and they flashed brightly in even that dull illumination.

“Watch that old fool,” said Morgan.

“You handle the Kid, then,” said Deacon.

He had cone up to his partner’s shoulder, a great contrast to the other.

He was one of those little, heavy-shouldered men with legs so bowed that

they waddled like ducks in walking. He looked like a sailor. There was

something free-swinging, frank, and easy about his hearing, and about his

face.

“Here, Bud,” said the other, “ain’t you gunna keep the old man in hand?”

“Yeah,” said Bud, rising in turn, “I’m gunna keep him in hand, all

right.”

He turned a grim face upon his father.

“You set down and don’t make no fool or yourself, no more,” said he.

Old Dad looked as though be had been struck with a heavy fist.

“You ain’t with ‘em, Bud,” said he. “You can’t be with ‘em, ain’ the

Kid—ain’ any guest right in our own house. There ain’t no Trainor so

dog-gone low as all of that! Bud, Bud, look me in the eye and tell me

that I got the wrong steer about you, just now!”

“Aw, shut up and set down,” commanded the big son. “Use your eyes. You

ain’t a hoss that’s gotta keep neighin’ till you’ve lost your wind—the

way the Kid was sayin’!”

“Was it your horse that neighed, Deacon?” asked the Kid.

“What made you guess that?” said the Deacon, curiously.

“The last time I saw you, you were riding a piebald speed-burner, with

the nerves of a sick woman and the look of a fool. That’s the sort of a

horse that doesn’t know the right time for making a noise. You had to

pinch his nose, didn’t you?”

“I about pulled the nose off of him,” agreed Deacon. “He’s a fool, that

gelding, but he sure can hump himself along. Fan him, Lefty. And fan him

good!”

Lefty, nothing backward in this work, went carefully through the clothes

of the Kid, searching his pockets and patting him all over to discover

weapons.

Old Dad Trainor, in the meantime, had slumped down into his chair and

remained with a leaden, hanging head.

To him, the Kid now addressed himself.

“Why, Dad,” he declared, “these are hard times. You can’t expect a man to

turn down a chance to pick up a few thousand as easily as this. How much

is your split, Bud?”

“None of your damn business,” answered Bud.

“Oh, Bud, Bud!” said his mother.

Suddenly he shouted, white and crimson: “Leave me be, will ya? The two of

ya leave me be! You kep’ me out here all these years takin’ care of you,

didn’t you? You never give me no chance to make anything decently, did

ya? Now shut your faces and leave me be, while I make some money on my

own account. I wanted a start, and I’ve got it.”

His mother, looking like one who sees a ghost, stared straight before

her, pressing her folded hands first against her mouth, and then against

her breast.

“Take it easy,” urged the Kid. “I’ll be out of this mess, perhaps, before

long. And I’ll never come after Bud, if that’s what you worry about.

Bud’s human, that’s all, and he’s been hungry for a long time!”

Dad Trainor lifted his head and looked with hollow eyes at the Kid, but

he said nothing; and Ma Trainor, also, was mute.

In the meantime, as the weapons were produced from the person of the Kid,

various comments were made upon them.

First of all, out came a sleek Colt of the old single-action model from a

spring holster beneath his left armpit.

Comments (0)