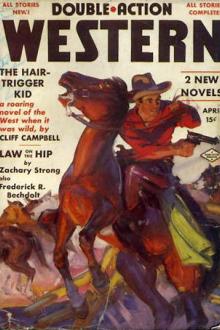

The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕

"The curtain ain't up," said the sheriff, "but I reckon that the stage is set and that they's gunna be an entrance pretty pronto."

"Here's somebody coming," said Georgia, gesturing toward the farther end of the street.

"Yeah," said the sheriff, "but he's comin' too slow to mean anything."

"Slow and earnest wins the race," said another.

They were growing impatient; like a crowd at a bullfight, when the entrance of the matador is delayed too long.

"We're wasting the day," said Milman to his family. "That's a long ride ahead of us."

"Don't go now," said Georgia. "I've got a tingle in my finger tips that says something is going to happen."

Other voices were rising, jesting, laughing, when some one called out something at the farther end of the veranda, and instantly there was a wave of silence that spread upon them all.

"What is it?" whispered Milman to the sheriff.

"Shut up!" said the sheriff. "They say th

Read free book «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Max Brand

- Performer: -

Read book online «The Hair-Trigger Kid by Max Brand (best sci fi novels of all time TXT) 📕». Author - Max Brand

“Why didn’t you stay in Dry Creek?”

“Would you like to go to sleep inside the den of a wild cat?”

The other nodded.

“Well,” he said, “you’ve missed a fine chance, Kid. If I was you, I’d go

back to Dry Creek and see Shay under a white flag and make friends.

Nobody is gunna get on in this part of the world unless he’s a friend of

Shay’s.”

“There’s only that question,” said the Kid. “When you see him, you ask

him, will you? I’d give a lot to find out.”

“You think that Shay double-crossed him?”

“Double-crossed him?” said the Kid, gently. “Why, man, Coleman was sixty

years old. Who would double-cross a man that old?”

The other watched his face cautiously, and seemed to perceive a tone of

iron in that last remark.

“I dunno anything about it,” he said shortly. “Was Coleman a great friend

of yours?”

“Coleman? Oh, not particularly. I just barely knew him. He took me in

when I was hungry, once, and again he showed me the way out when I was in

a tight hole, and another time he saved my life when I was cornered by a

gang. Outside of that, he didn’t have any claim on me.”

Dixon frowned, and then stood up.

“I guess I know what you mean,” said he. “If I should find out about

Coleman—I’ll let you know.”

“Thanks,” said the Kid, showing his teeth as he smiled. “I take that

kindly from you, Champ.”

“I’ll tell you one other thing, Kid,” burst out Dixon. “If you want to

wear your scalp long, don’t stay in this country unless you’ve made it up

with Shay.”

“He has everything under his thumb, has he?”

“He has everything under his thumb, and that’s a fact”

“I’m glad to know that,” said the Kid, “and I hope that we’ll be

friendly. You tell him something from me, will you?”

“Of course I will, when I see him.”

The Kid looked up at him with the same smile.

“Tell him that unless I hear from him soon I’m going to have to drop in

on him in a hurry and open him up to learn the truth about Coleman.”

“Open him up?” asked Dixon, starting.

“Yes,” said the Kid. “If I can’t hear it from his mouth, I might find it

in his heart, or his liver. And if I fail—he’ll make good dog food,

anyway. That’s all I’d like to have you tell him from me, old-timer.”

Dixon, during the last part of this speech, had been backing away from

the Kid, frowning. Now, without a word, he turned to his horses, saddled

one, and was about to climb into the saddle, when he paused, fumbling at

the saddle straps.

The Kid was watching closely, though from the corner of his eye, while he

saddled the mare. Then, glancing in the direction in which his companion

was looking, he saw from the top of a distant hill the flicker of a

light, as though the sun were glittering upon the face of a moving glass.

Suddenly he found that Dixon was staring at him closely, critically.

“Yes,” said the Kid, still smiling, “it looks as though your friend Shay

had the country by the throat. There he is, winking at you across all

those miles, old-timer. Wink back, when you get a chance, and tell him

that I’m waiting for my answer.”

Dixon, without answering, flung himself on the back of his horse. He

seemed about to ride straight off, but changing his mind at the last

moment, he returned to the Kid and leaned a little from the saddle.

“I’ll tell you something,” said he, “and it don’t cost you nothin’ to

hear it. You’re gunna be marked down in a pretty short while. Get out of

this neck of the woods. I ain’t got nothin’ agin’ you. I like you fine.

But—I tell you to start movin’, Kid!”

The latter watched him carefully.

“I believe you, old son,” said he. “I’d better get moving, before you

have to start on my trail. Is that it?”

“Put it any way you want to. You think that you know a lot, Kid. You

don’t know nothin’. You give Shay the run today and think you’re the top

dog. Why, that don’t mean nothin’. He don’t fight because he’s proud. He

fights because he wants your blood. And he’d sooner use hired hands than

his own. Kid, watch yourself. So long. I’ve said a pile too much,

already!”

He jerked his horse around and made off at once along the trail toward

Dry Creek, while the Kid looked after him with a certain combination of

pity, contempt and kindness. Then he mounted and went in the opposite

direction, riding slowly, with a thoughtful cant to his head.

For not more than a half mile did the Kid keep along the trail, and then,

so seriously did he take the friendly warning of Champ Dixon, that he

turned aside and cut through the open country, winding up and down

through the ravines and over the hills patiently. There was a great deal

to occupy his mind during this ride, and chiefly the figure of Champ

Dixon.

That man had been famous in story and legend and fact for many a day. But

now, like many another legend of the Far West, the Kid had met it,

mastered it, put it behind him. It did not seem to him a thing entirely

of rags and tatters. It was merely the boiling down of a great, great

giant into a quite ordinary man.

And yet he could see the other side of the chance, as well.

As, for instance, if the mare had not spotted the approach of Dixon in

the distance, and that red Indian of a man had found the Kid before the

Kid found him. Then, there was a little doubt. Dixon would have increased

his fame endlessly by a good, well-aimed bull’s-eye, the center of the

target being the forehead of the Kid. That was the sort of a man Dixon

was. He lived for glory. And, beyond question, he had needed nothing but

an audience, this day, to force him to take the most hopeless chances and

fight out the battle against the Kid and all the odds of circumstance.

A comfortable warmth was in the heart of the Kid, as he thought of this.

The next instant the mare limped, and he dropped down from the saddle

instantly to see what was wrong.

He found the trouble in a moment. She had cast a shoe.

This made him shake his head. For the terrain over which they were

traveling was very bad, constant outcroppings of rock making the way

dangerous for a shoeless horse. Even the regular trail was bad enough,

but the cross-country work much worse.

From his saddlebag, with a buckskin string and a flat, thick piece of

leather, he improvised rapidly, a sort of moccasin, and mounting again,

he rode on through the broken sea of hills.

He went more carefully now, however, and studying the landmarks before

him, he presently turned down a ravine that pointed to the left of his

way. He wound the bend of this in the dusk of the day, while the sun was

still rosy on the upper mountains, but here in the heart of the narrow

valley the twilight was already so deep that he could see the faint

shining of a light before him, dull as the evening star just after the

sun is down.

Toward this he went, the mare picking her way adroitly. She seemed to

realize as well as her master that that naked foot might be a cause of

trouble in the future.

As he came near the house, he heard a clattering of hoofbeats, and

looking up the hill, he saw a couple of riders coming over the crest,

horses and men outlined like black, strangely moving cardboard figures

against the red of the western sky.

This made him rein up, but, as he studied the horsemen, he made out that

only one was a man. The other form was certainly no more than a small

boy.

The Kid went on, more at ease, and now he could see the flat shine of the

pool beside the cabin, the dim image of the tree at its verge, the

straggling march of the shrubbery up the slope, and the little squat

cabin itself, looking too small for human habitation.

It grew a little on nearer approach. He saw the woodshed, and the little

corral. But the whole place had an air not of habitation so much as an

accidental touch of human life in the midst of the wilderness. Men who

lived here remained not for what they won from the soil, but for the

freedom which they breathed in from the ground. They might be either

thoroughly fine fellows, beyond price, or rascals not worth their salt.

When the Kid was close he called out: “Trainor! Trainor!”

A loud voice whooped instantly in answer: “Who’s there?”

“A friend!”

“Come on in, friend!”

The swinging light of a lantern appeared outside of the door of the

shack, and into the uncertain circle of this light rode the Kid.

He found that the lantern was held by a big bearded fellow with shoulders

wide enough to have lifted the whole house behind him, it seemed. He was

not more than thirty, but he looked older. Frost in winter and burning

sun in summer put their mark on the skin of a man, and all the beards in

the world cannot mask the pain of labor which appears in the eyes.

“I nearly forgot where your place was, Bud,” said the Kid.

At his voice, Trainor lifted the lantern high—and then almost dropped

it.

“It’s the Kid!” he exclaimed.

“Shut up!” cautioned the latter, swinging down from the saddle,

nevertheless, and grasping the hand of the other.

“It’s all right,” said Trainor. “There ain’t nobody here but pa and ma

and my kid cousin, that I’ve just fetched out from Dry Creek. Davey’s

been talkin’ about nothin’ but you. He’s the kid that you give the ride

to in Dry Creek. Here, Davey. Here’s a surprise for you!”

Davey came, hurrying. And as he rushed into the lantern light, and

blinked at the face and form of the Kid, his eyes opened and his mouth

also.

“By golly,” said Davey. “It’s the Kid. Hello, Kid. You ain’t forgot me,

have you?”

“I haven’t forgotten you,” said the Kid. “I don’t forget your kind,

old-timer, to the end of my days. Bud, I’ve lost a shoe off this mare

somewhere on the way across.”

“On the trail?”

“No. I would have gone back for it, if I had. Have you anything in the

way of shoes around here?”

“I’ve got some that the rust has been gnawin’ at for a long time. You

take a look. Hey, Davey. You fetch out that bunch of shoes that’s hangin’

agin’ the wall of the shed. I got a kind of a forge, Kid, besides. You

come to the right place.”

“Aye,” said the Kid. “I remembered that forge when I was five or six

miles away. It’s a forewitted fellow who has a forge on his place, Bud.”

The latter accepted the compliment with a grunt.

“The old man done the thinkin’ about that. He got it in the

Comments (0)