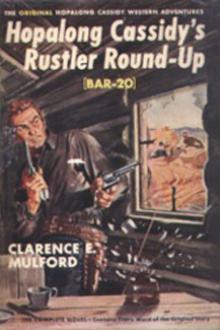

''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕

"I know how you feel, Mr. Boyd. Have you seen your father since you landed?"

Tom reluctantly shook his head. "It would only reopen the old bitterness and lead to further estrangement. No man shall ever speak to me again as he did--not even him. If you should see him, Jarvis, tell him I asked you to assure him of my affection."

"I shall be glad to do that," replied the clerk. "You missed him by only two days. He asked for you and wished you success, and said your home was open to you when you returned to resume your studies. I think, in his heart, he is proud of you, but too stubborn to admit it." As he spoke he chanced to glance through the window of the store. "Don't look around," he warned. "I want to tell you t

Read free book «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕» - read online or download for free at americanlibrarybooks.com

- Author: Clarence E. Mulford

- Performer: -

Read book online «''Bring Me His Ears'' by Clarence E. Mulford (howl and other poems TXT) 📕». Author - Clarence E. Mulford

The landing was a busy place. Piles of cordwood and freight, the latter in boxes, barrels, and crates, flanked the landing on three sides; several kinds of new wagons in various stages of assembling were scenes of great activity. Most of these were from Pittsburg and had come all the way by water. A few were of the size first used on the great trail, with a capacity of about a ton and a half; but most were much larger and could carry nearly twice as much as the others. Great bales of Osnaburg sheets, or wagon covers, were in a pile by themselves, glistening white in their newness. It appeared that the cargo of the John Auld had not yet been transported up the bluff to the village on the summit.

The landing became very much alive as the fur company's boat swung in toward it, the workers who hourly expected the Missouri Belle crowding to the water's edge to welcome the rounding boat, whose whistle early had apprised them that she was stopping. Free negroes romped and sang, awaiting their hurried tasks under exacting masters, the bosses of the gangs; but this time there was to be no work for them. Vehicles of all kinds, drawn by oxen, mules, and horses, made a solid phalanx around the freight piles, among them the wagons of Aull and Company, general outfitters for all kinds of overland journeys. The narrow, winding road from the water front up to and onto the great bluff well back from the river was sticky with mud and lined with struggling teams pulling heavy loads.

When the fur company boat drew near enough for those on shore to see its unusual human cargo, both as to numbers and kinds, conjecture ran high. This hardy traveler of the whole navigable river was no common packet, stopping almost any place to pick up any person who waved a hat, but a supercilious thoroughbred which forged doggedly into the vast wilderness of the upper river. Even her curving swing in toward the bank was made with a swagger and hinted at contempt for any landing under a thousand miles from her starting point.

Shouts rang across the water and were followed by great excitement on the bank. Because of the poor condition of the landing she worked her way inshore with unusual care and when the great gangplank finally bridged the gap her captain nodded with relief. In a few moments, her extra passengers ashore, she backed out into the hurrying stream and with a final blast of her whistle, pushed on up the river.

Friends met friends, strangers advised strangers, and the accident to the Belle was discussed with great gusto. Impatiently pushing out of the vociferous crowd, Joe Cooper and his two companions swiftly found a Dearborn carriage which awaited them and, leaving their baggage to follow in the wagon of a friend, started along the deeply rutted, prairie road for the town; Schoolcraft, his partner, and his Mexican friend sloping along behind them on saddle horses through the lane of mud. The trip across the bottoms and up the great bluff was wearisome and tiring. They no sooner lurched out of one rut than they dropped into another, with the mud and water often to the axles, and they continually were forced to climb out of the depressed road and risk upsettings on the steep, muddy banks to pass great wagons hopelessly mired, notwithstanding their teams of from six to a dozen mules or oxen. Mud-covered drivers shouted and swore from their narrow seats, or waded about their wagons up to the middle in the cold ooze. If there was anything worse than a prairie road in the spring, these wagoners had yet to learn of it.

CHAPTER VIIITHE NEW SIX-GUN

Independence was alive all over, humming with business, its muddy streets filled with all kinds of vehicles drawn by various kinds and numbers of animals. Here a three-yoke ox team pulled stolidly, there a four-mule team balked on a turn, and around them skittish or dispirited horses carried riders or drew high-seated carriages. The motley crowd on foot picked its way as best it could. Indians in savage garb passed Indians in civilization's clothes, or mixtures of both; gamblers rubbed elbows with emigrants and made overtures to buckskin-covered trappers and hunters just in from the prairies and mountains, many of whom were going up to Westport, their main rendezvous. Traders came into and went from Aull and Company's big store, wherein was everything the frontier needed. Behind it were corrals filled with draft animals and sheds full of carts and wagons.

Boisterous traders and trappers, in all stages of drunkenness, who thought nothing of spending their season's profits in a single week if the mood struck them, were still coming in from the western foothills, valleys, and mountains, their loud conversations replete with rough phrases and such names as the South Park, Bent's Fort, The Pueblo, Fort Laramie, Bayou Salade, Brown's Hole, and others. Many of them so much resembled Indians as to leave a careless observer in doubt. Some were driving mules almost buried under their two packs, each pack weighing about one hundred pounds and containing eighty-odd beaver skins, sixty-odd otter pelts or the equivalent number in other skins. Usually they arrived in small parties, but here and there was a solitary trapper. The skins would be sold to the outfitting merchants and would establish a credit on which the trapper could draw until time to outfit and go off on the fall hunt. Had he sold them to some far, outlying post he would have received considerably less for them and have paid from two hundred to six hundred per cent more for the articles he bought. As long as there was nothing for him to do in his line until fall set in, he might just as well spend some of the time on the long march to the frontier, risking the loss of his goods, animals, and perhaps his life in order to get better prices and enjoy a change of scene.

The county seat looked good to him after his long stay in the solitudes. Pack and wagon trains were coming and going, some of the wagons drawn by as many as a dozen or fifteen yokes of oxen. All was noise, confusion, life at high pressure, and made a fit surrounding for his coming carousal; and here was all the liquor he could hope to drink, of better quality and at better prices, guarantees of which, in the persons of numerous passers-by, he saw on many sides.

Rumors of all kinds were afloat, most of them concerning hostile Indians lying in wait at certain known danger spots along the trails, and of the hostile acts of the Mormons; but the Mormons were behind and the trail was ahead, and the rumors of its dangers easily took precedence. It was reported that the first caravan, already on the trail and pressing hard on the heels of spring, was being escorted by a force of two hundred United States dragoons, the third time in the history of the Santa Fe trade that a United States military escort had been provided. Dangers were magnified, dangers were scorned, dangers were courted, depending upon the nature of the men relating them. There were many noisy fire-eaters who took their innings now, in the security of the town, who would become as wordless, later on, as some of the tight-lipped and taciturn frontiersmen were now. Greenhorns from the far-distant East were proving their greenness by buying all kinds of useless articles, which later they would throw away one by one, and were armed in a manner befitting buccaneers of the Spanish Main. To them, easiest of all, were old and heavy oxen sold, animals certain to grow footsore and useless by the time they had covered a few hundred miles. They bought anything and everything that any wag suggested, and there were plenty of wags on hand. The less they knew the more they talked; and experienced caravan travelers shook their heads at sight of them, recognizing in them the most prolific and hardest working trouble-makers in the whole, long wagon train. Here and there an invalid was seen, hoping that the long trip in the open would restore health, and in many cases the hopes became realizations.

Joseph Cooper installed his niece in the best hotel the town afforded and went off to see about his wagons and goods, while Tom Boyd hurried to a trapper's retreat to find his partner and his friends. The retreat was crowded with frontiersmen and traders, among whom he recognized many acquaintances. He no sooner had entered the place than he was soundly slapped on the shoulder and turned to exchange grins with his best friend, Hank Marshall, who forthwith led him to a corner where a small group was seated around a table, and where he found Jim Ogden and Zeb Houghton, two trapper friends of his who were going out to Bent's trading post on the Arkansas; Enoch Birdsall and Alonzo Webb, two veteran traders, and several others who would be identified with the next caravan to leave.

"Thar's one of them danged contraptions, now!" exclaimed Birdsall, pointing to the holster swinging from Tom's broad belt. "I don't think much o' these hyar newfangled weapons we're seein' more an' more every year. An' cussed if he ain't got a double-bar'l rifle, too! Dang it, Tom, don't put all yer aigs in one basket; ain't ye keepin' no weapons ye kin be shore on?"

"Thar both good, Enoch," replied Tom, smiling broadly.

"Shore they air," grunted Birdsall's partner. "Enoch don't reckon nothin's no good less'n it war foaled in th' Revolutionary War, an' has got whiskers like a Mormon bishop. Fust he war dead sot ag'in steamboats; said they war flyin' in th' face o' Providence an' wouldn't work, nohow. Then he said it war plumb foolish ter try ter take waggins inter Santer Fe. Next he war dead sot ag'in mules fer anythin' but packin'. Now he's cold ter caps an' says flints war made 'special by th' Lord fer ter strike fire with—but, he rides on th' steamboats when he gits th' chanct; he's taken waggins clean ter Chihuahua, drivin' mules ter 'em; an' he's sorter hankerin' fer ter use caps, though he won't admit it open. Let him alone an' watch him try ter borrer yer new pistol when th' Injuns try ter stampede th' animals. He's a danged old fool in his talk, but you jest keep an eye on him. Thar, I've said my say."

"An' a danged long say it war!" snorted Enoch, belligerently. "It stands ter reason that thar pistol can't shoot 'em out o' one bar'l plumb down the dead center of another every time! An' suppose ye want ter use a double charge o' powder, whar ye goin' ter put it in them danged little holes? Suppose yer caps hang fire—what then, I want ter know?"

"S'posin' th' wind blows th' primin' out o' yer pan?" queried Zeb. "S'posin' ye lose your flint? S'posin' yer powder ain't no good? S'posin' ye ram down th' ball fust, like ye did that time them

Comments (0)